I would first like to thank Professor W. L. Idema for inspiring me to translate The Drunken Mans Talk and for his patient advice concerning the translation of the works more abstruse phrases. I am also extremely grateful for the advice of the two anonymous reviewers of the manuscript who saved me from many a mistranslation, in addition to the assistance of my brother-in-law, Mr. Liao Chien-lang. I would like to thank Lorri Hagman, Jacqueline Volin, and Caroline Knapp whose diligent editing and suggestions have polished the style to a higher level of beauty. Thanks also to my former student, Vaughn Rogers, who acted as guinea pig for early drafts of the introduction. Finally, without the support and intellectual companionship of my wife, Emily, this book would never have reached fruition. I also acknowledge the editorial board and associates of Renditions for their permission to reproduce the story of elopement that appears in the second chapter.

TRANSLATORS INTRODUCTION

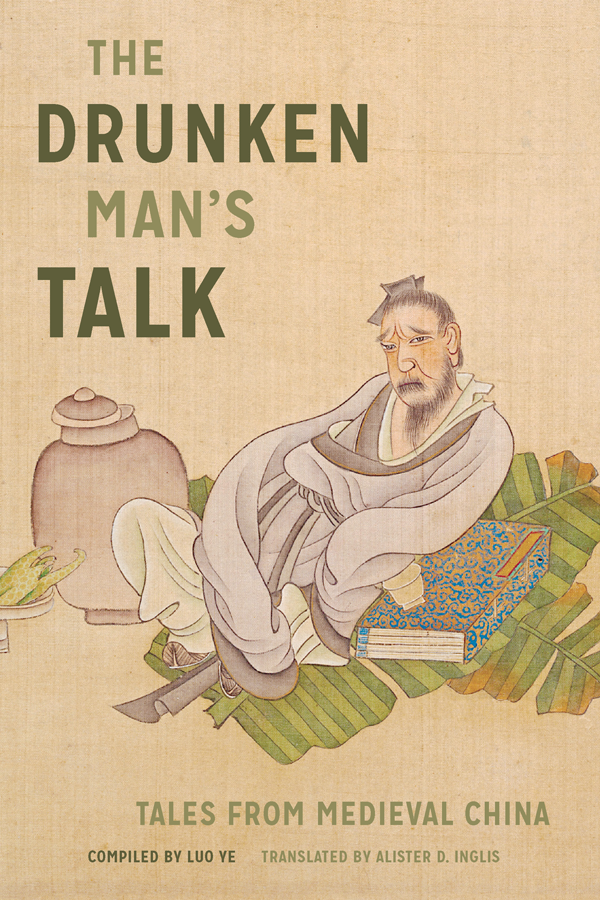

In 1940, while war was raging in both Europe and China, an intriguing discovery was made in Japanone that would offer enthusiasts of traditional Chinese literature an Aladdins cave of exciting literary treasures. A single imprint of a long lost medieval Chinese book titled The Record of a Drunken Mans Talk (Xinbian zuiweng tanlu; hereafter The Drunken Mans Talk) was discovered in a private library belonging to a former samurai clan, the Date (pronounced dah-te). While the title might tempt the specialist to associate it with the famous man of letters Ouyang Xiu (10071072), given that the drunken man was Ouyangs sobriquet andlike its authorhe too hailed from Luling, the lack of any significant reference to him throughout the text suggests that the phrase was probably intended as a generic cultural construct unrelated to the great man. The book presented something of a mystery as it included no date or place of printing, nor were there any bibliographical records to indicate how it found its way into the Date familys collection. Nevertheless, it immediately attracted the attention of Japanese scholars who published an article announcing its rediscovery. Such was its importance to Chinese literary history that a facsimile copy was published in Tokyo the same year.

The only clue as to its provenance was hearsay; family tradition held that it had come to Japan via Korea. This is highly plausible given the familys history. The clans founder, Date Masamune (15671636), sent troops to support Toyotomi Hideyoshis (15371598) invasion of Korea (15911598). It is likely that The Drunken Mans Talk entered their collection around that time as did many other books that the family acquired. If so, this date concurs nicely with the only known references to the book in late sixteenth-century Chinese sources: in Catalogue of the Literary Treasure Studio (Baowen tang completed in 1407 and incorporating all the available literature in the imperial libraries, included a story titled Su Xiaoqing from The Drunken Mans Talk not found in the Date imprint. I have therefore translated and included this hitherto lost piece in the appendix to the present volume. This is all that is known about the works textual history, indicating that it did not circulate widely in China.

All we know about the author of The Drunken Mans Talk, Luo Ye, derives from the imprints cover page. It tells us only that he came from Luling, the old name for the modern Jian in Jiangxinothing else is given. This dearth of biographical information suggests that Luo Ye may have been a failed candidate for the examinations that most educated men of the period undertook in the hope of serving their country and emperor, a common career for Confucian scholars. He may also have been a local teacher. Today we know him only through his literary collection, and dating the work is therefore difficult.

Internal dates, literary theme and style, diction, and the like suggest that The Drunken Mans Talk is either of Southern Song (11271279) or possibly Yuan/Mongol (12791368) dynasty provenance. This opens the possibility that the Date familys imprint was printed in either the Song or Yuan period, which would place it in an austere company of extremely rare books to have survived the passing centuries. It is, however, more likely a Ming dynasty (13681644) recension or reprint of an earlier edition. Unless further evidence emerges, we will probably never know.

The Drunken Mans Talk is important to scholars and students of traditional Chinese literature for several reasons. First, its initial chapter imparts a wealth of knowledge about professional storytelling during the late Southern Song and Yuan dynasties. This is all the more significant given the lack of similar sources. In view of the mutual influence of professional and informal storytelling throughout Chinas imperial history, anyone seriously interestedin this literature has much to gain by understanding professional storytelling. Second, The Drunken Mans Talk is a rich collection of short stories written in classical Chinese, the language of the educated elite, with a status akin to that of Latin in medieval Europe, as opposed to the vernacular which later became a more acceptable medium for narrative works. Not only are these stories essential reading for the specialist, their freshness and charm renders them worthy of the attention of the general reader who seeks to understand social conditions and the intellectual milieu of Chinese society around the time of the Mongol invasion.

The Drunken Mans Talk is an eclectic collection of short works of various genres: poetry, jokes, legal rulings, factual accounts, and anecdotes, in addition to polished prose narratives. The earliest derive from the Six Dynasties period (420581) while many of the latest include a Southern Song (11271279) temporal setting. Stories and poetry from the illustrious Tang dynasty (618907) are particularly numerous, reflecting the enduring interest of later generations in this dynasty, well after its collapse. While we cannot be certain as to Luo Yes direct sources, it is likely that many of the Tang dynasty short stories derive from the massive Tang compilation, Extensive Gleanings from the Period of Great Peace (Taiping guangji). Other pieces seem to have been copied from various Tang and Song literary works. Luo Yes chapter on the brothel district of the Tang capital, Changan, is largely copied verbatim from a Tang memoir,