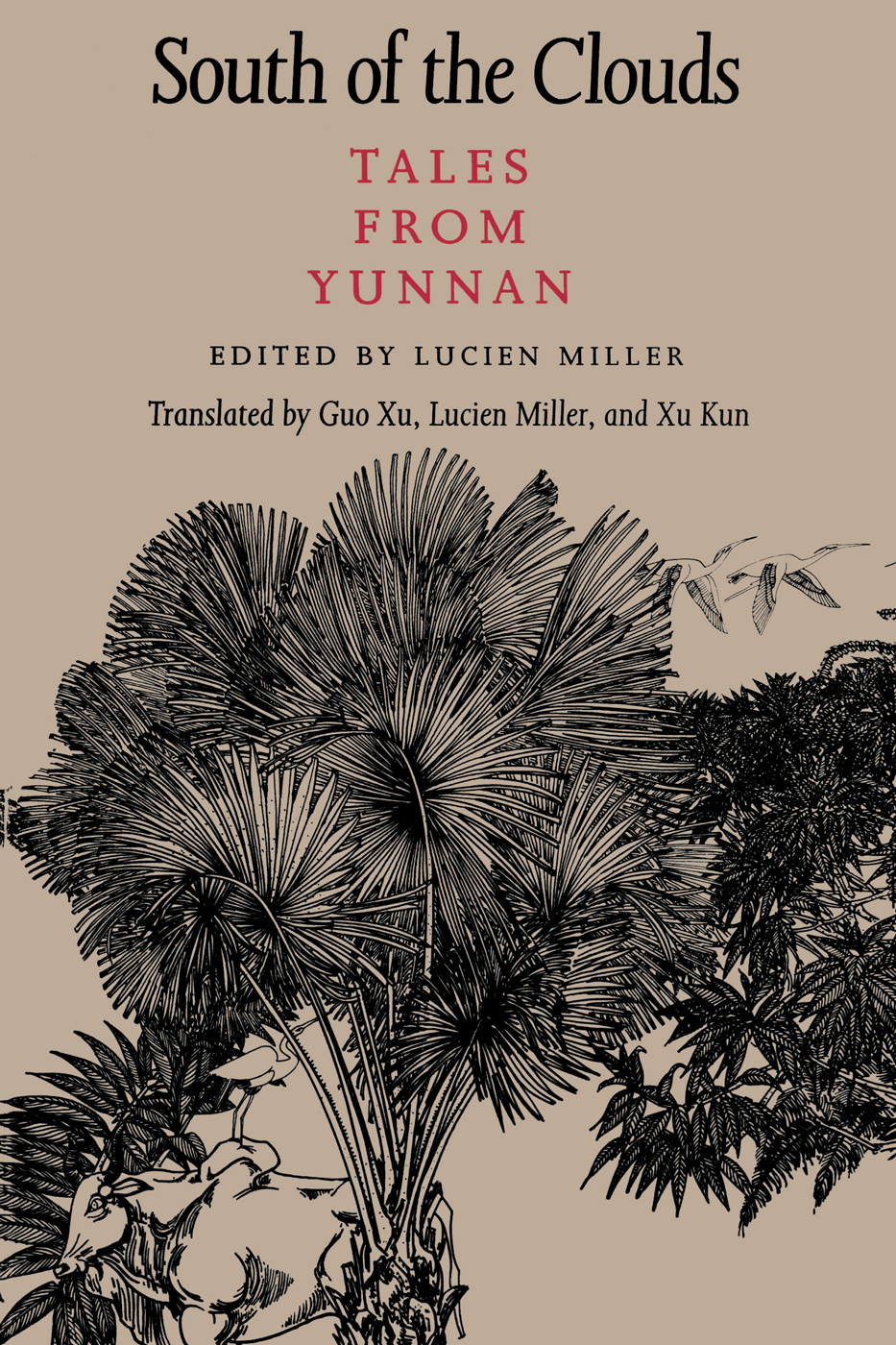

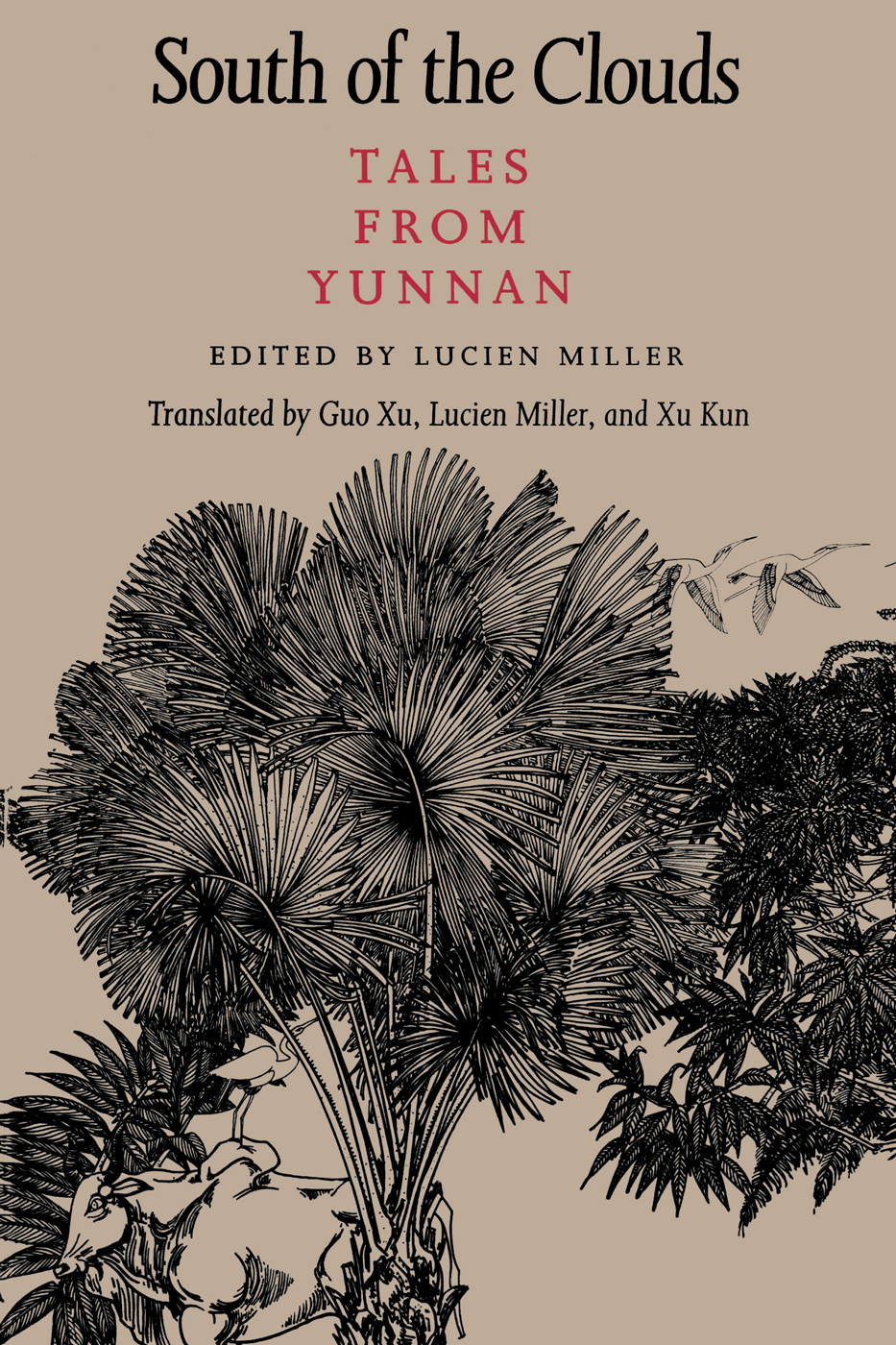

SOUTH OF THE CLOUDS

South of the Clouds

TALES

FROM

YUNNAN

EDITED BY LUCIEN MILLER

Translated by Guo Xu, Lucien Miller, and Xu Kun

A MCLELLAN BOOK

University of Washington Press Seattle & London

This book is published with the assistance of a grant from the McLellan Endowed Series Fund, established through the generosity of Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams.

This volume is the result of a joint project sponsored by Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, Yunnan Province, Peoples Republic of China, and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts.

Copyright 1994 by the University of Washington Press

Printed in the United States of America

Design by Audrey Meyer

Composition by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

South of the clouds : tales from Yunnan / edited by Lucien Miller :

translated by Guo Xu, Lucien Miller, and Xu Kun

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-295-97293-9 97348-X (pbk.)

1. TalesChinaYunnan Province. I. Miller, Lucien. II. Guo, Xu. III. Xu, Kun.

GR336.Y86S68 1994

398.2095135dc20 93-36563

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI A39.38-1984.

Jacket/cover illustration: Yunnan landscape, reproduced courtesy of the artist, Ting Shao Kuang. Part title motif: Yi embroidered head ornament, from Yunnan shaoshu minzu zhixiu wenyang (Yunnan Province Nationalities Research Institute, 1987), p. 41.

Contents

LUCIEN MILLER

LUCIEN MILLER

XU KUN

Drung

Jino

Lisu

Miao

Blang

Buyi

Dai

Dai

Sui

Yi

Blang

Tibetan

Bai

Hani

Zhuang

Kucong

Mongol

Wa

Yao

Jingpo

Yi

Lahu

Yi

Lahu

Jingpo

Hui

Naxi

Nu

Primi

Achang

Deang

Dai

Yao

Bai

Dai

LUCIEN MILLER

In Memoriam

Winifred C. Miller

The Reverend Caspar Caulfield, C.P.

Preface

A phrase that appears frequently in Maxine Hong Kingstons novel-biography-autobiography Woman Warrior is talk-story. A literal translation of a common Chinese phrase, jiang gushi (to tell a story), talk-story refers to the oral folk art of story telling, of which the mother in the book, Brave Orchid, is a master. She weaves oral stories to ward off or invoke ghosts, to terrorize her little girl into quiescent submission to her maternal authority, or liberate her from a morbid, neurotic shyness which makes her utterly helpless in America. Through talk-story, she teaches her child Chinese legends and pseudo-history that force her to fantasize and escape reality, and to create some powerful, nearly believable myths about the familys past which make the child look hard at the present, and perhaps even face the future. In the oral art of story telling found in minority folk stories from Yunnan Province, we see the roots of talk-story, and vestiges of the live performances that sweep adults and children off their feet.

This book originates in a little talk-story from Yunnan. The contents and narrator are unknown, but the telling of the story led to the gathering of tales and translation work behind this volume, and the cooperative support of universities in China and the United States. In the summer of 1984, Deidre Ling, formerly vice-chancellor at the University of Massachusetts, happened to visit Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, while touring Chinese institutions with which the University of Massachusetts has exchange agreements. At Yunnan Normal University a member of the Chinese faculty told her in English a Yunnan minority folktale that she found particularly moving. We have many more stories translated from the minority languages into Chinese, the man pointed out. If you liked that one, youll like some of the others even better. The only problem is that few of them have been translated into English. One story led to another, and before long, Ms. Ling, armed with a magazine (Shan cha [Rhododendron]) full of examples and a volume or two of minority song epics and tales, returned to her university, intending to find someone interested in translating Yunnan minority folk stories. In the spring of 1985, I began translating a few sample stories with a graduate student in comparative literature, Zhao Qiguang, and the following summer went to Kunming. There I was the guest of Yunnan Normal University, and was taken by my hosts to visit several minority areas in Yunnan and to interview storytellers and singers.

During the spring of 1986, Guo Xu, professor of English in the Foreign Languages Department, and Xu Kun, associate professor of Chinese and a specialist in Yunnan minority folklore, both from Yunnan Normal University, were hosted by the University of Massachusetts. Xu Kun had spent much of the previous year reviewing massive amounts of Yunnan folk materials, including his own extensive personal collection. From some forty volumes of works published in Chinese, he selected 150 pieces, representing each of the twenty-five minorities found in Yunnan, and belonging to the folk literature genres of tale, myth, and legend. I read these and chose fifty-four for translation from Chinese to English, on the basis of their variety and what I felt would be aesthetically appealing to the informed general reader or university student interested in folk literature and China. From mid-March until the end of June 1986, Guo Xu, Xu Kun, and I met for three or more hours, two to three times a week for our translation work. I do not think we ever argued, but sometimes our sessions together were emotionally exhausting. The particular advantages we have as translators are that two of usGuo Xu and myselfread and speak both English and Chinese, while Xu Kun is a teacher of Yunnan folklore and an expert in minority folk literature. Of special importance to the translation of Yunnan folk literature is the fact that both Guo Xu and Xu Kun are natives of Yunnan, fluent in Yunnanese dialect, and familiar with local culture, foods, geography, climate, flora, and fauna encountered in the stories. In the course of translating, Guo Xu and I would check one anothers translation, whether literal or free, from the vantage point of someone who is a native speaker of one language and a scholar of the second, and Xu Kun would clarify folklore and minority questions. The whole process of translating was an experience of talk-story, producing variant tales which formed the final version. Readers interested in our efforts to translate and talk-story will find an example under Translation Strategies in the General Introduction.

For the readers information, responsibility for this book was shared as follows: Xu Kun wrote the Introduction to Yunnan National Folk Literature and an essay on the minorities, information from which is included in the Appendix, which was compiled by myself. I served as editor, wrote the Preface and General Introduction, and compiled the Bibliography and Glossary.

Next page