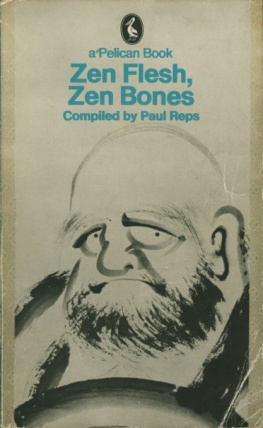

ZEN FLESH, ZEN BONES

Compiled by

Paul Reps

Table of Contents

Foreword

This book includes four books:

101 Zen Stories was first published in 1919 by Rider and Company, London, and David McKay Company, Philadelphia. These stories recount actual experiences of Chinese and Japanese Zen teachers over a period of more than five centuries.

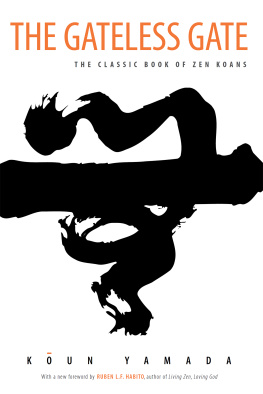

The Gateless Gate was first published in 1934 by John Murray, Los Angeles. It is a collection of problems, called koan that Zen teachers use in guiding their students toward release, first recorded by a Chinese master in the year 1228.

10 Bulls was first published in 1935 by DeVorss and Company, Los Angeles, and subsequently by Ralph R. Phillips, Portland, Oregon. It is a translation from the Chinese of a famous twelfth century commentary upon the stages of awareness leading to enlightenment and is here illustrated by one of Japans best contemporary woodblock artists.

Centreing, a transcription of ancient Sanskrit manuscripts, first appeared in the Spring 1955 issue of Gentry magazine, New York. It presents in ancient teaching, still alive in Kashmir and parts of India after more than four thousand years that may well be the roots of Zen.

Thanks are due the publishers named above for permission to gather the material together here. And most of all am I grateful to Nyogen Senzaki, homeless monk exemplar-friend collaborator, who so delighted with me in transcribing the first three books, even as that prescient man of Kashmir, Lakshmanjoo, did on the fourth.

*

The first Zen patriarch Bodhidharma brought Zen to China from India in the sixth century. According to his biography recorded in the year 1004 by the Chinese teacher Dogen after nine years in China Bodhidharma wished to go home and gathered his disciples about him to test their apperception.

Dofuku said: In my opinion truth is beyond affirmation or negation, for this is the way it moves.

Bodhidharma replied: You have my skin.

The nun Soji said: In my view, it is like Anandas sight of the Buddha-landseen once and for ever.

Bodhidharma answered: You have my flesh.

Dofuku said: The four elements of light, airiness, fluidity, and solidity are empty (i.e. inclusive) and the five skandas are No-things. In my opinion,

No-thing (i.e. spirit) is reality.

Bodhidharma commented: You have my bones

Finally Eka bowed before the masterand remained silent.

Bodhidharma said: You have my marrow.

*

Old Zen was so fresh it became treasured and remembered. Here are fragments of its skin flesh bones but not its marrownever found in words.

The directness of Zen has led many to believe it stemmed from sources before the time of Buddha, 500 BC. The reader may judge for himself, for he has here for the first time in one book the experiences of Zen, the mind problems, the stages of awareness and a similar teaching predating Zen by centuries.

The problem of our mind, relating conscious to preconscious awareness takes us deep into everyday living. Dare we open our doors to the source of am being? What are flesh and bones for?

PAUL REPS

101

ZEN STORIES

Transcribed by Nyogen Senzaki

and Paul Reps

These stories were transcribed into English from a book called the Shaseki-shu (Collection of Stone and Sand), written late in the thirteenth century by the Japanese Zen teacher Muju (the non-dweller), and from anecdotes of Zen monks taken from various books published in Japan around the turn of the present century.

For Orientals, more interested in being than in business the self-discovered man has been the most worthy of respect.

Such a man proposes to open his consciousness just as the Buddha did.

These are stories about such self-discoveries.

The following is adapted from the preface to the first edition of these stories in English.

Zen might be called the inner art and design of the Orient. It was rooted in China by Bodhidharma, who came from India in the sixth century, and was carried eastward into Japan by the twelfth century. It has been described as: A special teaching without scriptures, beyond words and letters, pointing to the mind essence of man seeing directly into ones nature, attaining enlightenment.

Zen was known as Chan in China. The Chan-Zen masters, instead of being followers of the Buddha, aspire to be his friends and to place themselves in the same responsive relationship with the universe, as did Buddha and Jesus. Zen is not a sect but an experience.

The Zen habit of self-searching through meditation to realize ones true nature, with disregard of formalism, with insistence on self-discipline and simplicity of living, ultimately won the support of the nobility and ruling classes in Japan and the profound respect of all levels of philosophical thought in the Orient.

The Noh dramas are Zen stories. Zen spirit has come to mean not only peace and understanding, but devotion to art and to work, the rich unfolding of contentment, opening the door to insight, the expression of innate beauty, the intangible charm of incompleteness. Zen carries many meanings, none of them, entirely definable. If they a defined they are not Zen.

It has been said that if you have Zen in your life, you have no fear, no doubt, no unnecessary craving, and no extreme emotion. Neither illiberal attitudes nor egotistical actions trouble you. You serve humanity humbly, fulfilling your presence in this world with loving-kindness and observing your passing as a petal falling from a flower. Serene you enjoy life in blissful tranquility. Such is the spirit of Zen, whose venture is thousands of temples in China and Japan, priests and monks, wealth and prestige, and often the very formalism it would itself transcend.

To study Zen, the flowering of ones nature, is no easy task in any age or civilization. Many teachers, true and false, have purposed to assist others in this accomplishment. It is from innumerable and actual adventures in Zen that these stories have evolved. May the reader in turn realize them in living experience today.

1. A Cup of Tea

Nan-in, a Japanese master during the Meiji era (1868-1912) received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in saved tea. He poured his visitors cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. It is overfull. No more will go in!

Like this cup, Nan-in said. You are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?

2. Finding a Diamond on a Muddy Road

Gudo was the emperors teacher of his time. Nevertheless, he used to travel done as a wandering mendicant. Once when he was on his way to Edo, the cultural and political center of the shogunate, he approached a little village mad Takenaka.

It was evening and a heavy rain was falling. Gudo was thoroughly wet. His straw sandals were in pieces. At a farmhouse near the village he noticed four or five pairs of sandals in the window and decided to buy some dry ones.

The woman who offered him the sandals seeing how wet he was invited him to remain for the night in her home. Gudo accepted, thanking her. He entered and recited a sutra before the family shrine. He then was introduced to the womans mother, and to her children. Observing that the entire family was depressed Gudo asked what was wrong.

My husband is a gambler and a drunkard, the housewife told him. When he happens to win he drinks and becomes abusive. When he losses he borrows money from others. Sometimes when becomes thoroughly drunk he does not come home at all. What can I do?

I will help him, said Gudo. Here is some money. Get me a gallon of fine wine and something good to eat. Then you may retire. I will meditate before the shrine.

Next page