More Praise for

The Gateless Gate

Kun Yamada was of that fine old breed of Japanese Zen Masterspiercing, disciplined, and always on point. The Gateless Gate distills his teaching and spirit marvelously. It is an essential text for anyone interested in the Zen koan, and in the process of Zen awakening.

Norman Fischer, former abbot of San Francisco Zen Center

Koans are the intimate family history of Zen. The awakened mind of the Zen ancestors is conveyed, but also their effort, sweat, pain, and joy. Kun Yamadas excellent translation and commentary helped opened the door to this world for many of us, and this new edition is sure to do so for many more.

Kyogen Carlson, abbot of Dharma Rain Zen Center

Here is the penetrating voice of a unique lay Zen master! The depth of Kun Yamada Roshis insight clearly reveals that the Dharma has nothing to do with East or West, Buddhism or ChristianityBuddha-nature is universal.

Eido Shimano, abbot of Dai Bosatsu Zendo

Kun Yamada

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2004 Kazue Yamada

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yamada, Kun, 1907-1989

Gateless gate / translated with commentary by Zen master Koun

Yamada. First Wisdom Ed.

p. cm.

Includes translation of Kui-kais Wu-men kuan.

ISBN 0-86171-382-6

1. Kui-kai. 1183_1260. Wu-men kuan. 2. Koan. I. Hui-kai,

11-83-1260. Wu-men kuan. English. 1990. II. title.

BQ9289.H843y34 1990

294.34dc20

2003114197

ISBN 978-0-86171-382-0

eBook ISBN 978-0-86171-971-6

Cover design by Richard Snizik. This book was set in Sabon 10/13. Cover art: Mu by Soen Nakagawa, used by permission of the Cambridge Buddhist Association

The footnotes to the interior text are editiorial insertions and do not derive from KounYamada.

Contents

Foreword

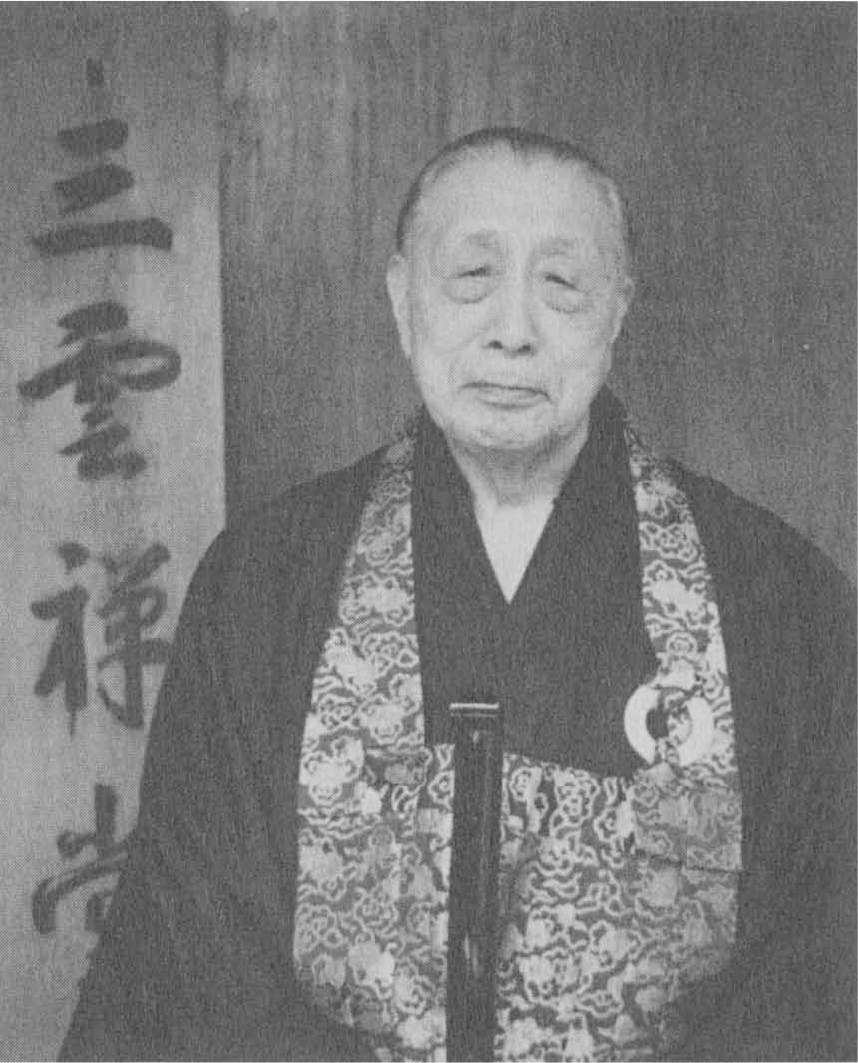

Kun Yamada Roshi ( 19061989 ), author of this volume of Zen talks on a thirteenth-century collection of koans entitled Gateless Gate (Wumen-kuan), will likely be remembered as one of the great Zen Masters of the twentieth century. Longtime head of the Sanbo Kyodan Association of the Teaching of the Three Treasures Zen community and main Dharma successor to Hakuun Yasutani Roshi ( 18851973 ), his teaching career spanned nearly three decades from the early 1960s up to his death. His own Dharma heirs are now leading Zen communities in Japan, America, and many other parts of the world.

Kun Yamada made a little-noticed debut in a Western-language publication, The Three Pillars of Zen, which he compiled and translated with Akira Kubota (now Jiun Roshi, current head of Sanbo Kyodan) and Philip Kapleau. Published under the latters name in 1965, that book, which has now come to be a staple in Zen reading in the West, included an account of Kun Yamadas Zen enlightenment experience ( kensho in Japanese). That account was written in 1953 under the byline of Mr. K.Y., a Japanese executive, age . This great man is also referred to by Rick Fields in his seminal work How the Swans Came to the Lake simply as the cigar-smoking hospital administrator who was Yasutanis disciple.

From 1970 to 1989 , living in Japan, I had the unique privilege of being able to practice Zen and receive regular guidance from Yamada Roshi. I continue to look back with profound gratitude to those years I sat in zazen with many others at San-un Zendo, the small Zen hall he had built with his wife, Kazue Yamada, adjacent to their own home, in Kamakura. The zendo was one hour by train southwest of Tokyo. Sanun means Three Clouds, referring to the Zen names of the three founding Teachers of the Sanb Kydan, namely, Daiun Harada (Great Cloud), Hakuun Yasutani (White Cloud), and Kun Yamada (Cultivating Cloud).

The culture and atmosphere at San-un Zendo, the setting where much of what is described in Three Pillars of Zen takes place, was marked early on by an emphasis on the attainment of kensho, an event that without doubt becomes a turning-point in a persons life of Zen.

However, from the late seventies up to his death in 1989 , Yamada Roshis teaching gradually shifted in focus, from the Zen enlightenment experience as such, to the personalization and genuine embodiment of this experience in the ongoing life of the true practitioner. So, although the experience of kensho may happen in the flash of an instant, its effective actualization in a persons daily life is considered to be the never ending task of a lifetime.

Yamada Roshi often noted that of those who may have had such an initial breakthrough experience, some get sidetracked from the path of awakening, as they idealize that experience, memorialize it, and cling to it. Holding on to ones kensho in this way becomes another kind of attachment that can be much more pernicious than other more mundane kinds. Thus, Yamada Roshi came to place great importance on vigilance in practice and continuing work with koans. Genuine fruit of Zen practice, he repeatedly maintained, is manifested when a human being is able to experience an emptying of ones ego, and truly live out ones humanity with a humble heart, at peace with oneself, at peace with the universe, and with a mind of boundless compassion.

It was in this later phase of his teaching career that Yamada Roshi came to address not just matters of practice geared toward attaining enlightenment, but likewise issues of daily life and contemporary society as the context for embodying this enlightenment. These included themes such as world poverty and social injustice, global peace, harmony among religions, and numerous other social and global concerns. The engagement with these issues was for Yamada Roshi a natural outflow of his life of Zen. His was a perspective grounded in the wisdom of seeing things clearly and a deep compassion for all beings in the universe enlightened by this wisdom. This was what he sought to convey to his Zen students. In short, the question of how a Zen practitioner is to live in daily life and relate to events of this world was a recurrent theme in his talks and public comments in this later phase.

Each teisho in The Gateless Gate gives the reader a glimpse into the depth and breadth of the Zen experience and vision of Kun Yamada Roshi. These talks will no doubt inspire those who are already engaged in Zen practice to a continued deepening of their experience, and also invite those who are not yet so engaged, to perhaps give it a try.

Ruben L.F. Habito (Keiun-ken)

Maria Kannon Zen Center, Dallas, Texas

Winter 2004

Preface to the Wisdom Edition

I am very happy that Wisdom Publications has decided to publish this new edition of The Gateless Gate, a collection of teisho by Kun Yamada Roshi in English. The first edition of the book was printed in 1979 , a quarter of a century ago. This book has been and will continue to be a trusted guide to all sincere Zen practitioners who wish to find out their own essential nature following the footpath of Shakyamuni Buddha.

Kun Yamada Roshi had an experience of great enlightenment in 1953 at the age of forty-six. At one point when he was around seventy years old, I had a chance to talk with him privately, and he showed me a work of his own calligraphy that read, Practice another years. He said that this would be his motto for his own future Zen practice. Thus he taught me that the enlightenment was very important for our Zen practice, but digesting the experience into our daily life was far more important than the experience itself. I was deeply impressed. The teachings in this book can doubtlessly be applied to all people who find themselves on the sincere way of Zen practice.

Next page