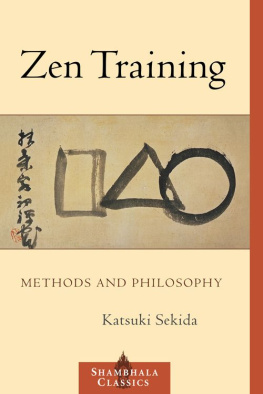

Katsuki Sekida brings to these works the same fresh and pragmatic approach that made his Zen Training so popular. The insights of a lifetime of Zen practice and his familiarity with Western as well as Eastern ways of thinking make him an ideal interpreter of the texts for the people of today.

Asahi Evening News

These notes are the fullest and most intelligent that have so far appeared in English.

Japan Times

Two Zen Classics is a product of Herculean labors, wrought with dedication and understanding.

Philip Kapleau

ABOUT THE BOOK

The strange verbal paradoxes called koans have been used traditionally in Zen training to help students attain a direct realization of truths inexpressible in words. The two works translated in this book, Mumonkan ( The Gateless Gate ) and Hekiganroku ( The Blue Cliff Record ), both compiled during the Song dynasty in China, are the best known and most frequently studied koan collections, and are classics of Zen literature. They are still used today in a variety of practice lineages, from traditional zendos to modern Zen centers. In a completely new translation, together with original commentaries, the well-known Zen teacher Katsuki Sekida brings to these works the same fresh and pragmatic approach that made his Zen Training so successful. The insights of a lifetime of Zen practice and his familiarity with both Eastern and Western ways of thinking make him an ideal interpreter of these texts.

KATSUKI SEKIDA (18931987) was by profession a high school teacher of English until his retirement in 1945. Zen, nevertheless, was his lifelong preoccupation. He began his Zen practice in 1915 and trained at Empuku-ji in Kyoto and Ryutaki-ji in Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture. He taught at the Honolulu Zendo and Maui Zendo from 1963 to 1970 and at the London Zen Society from 1970 to 1972.

Sign up to receive weekly Zen teachings and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes.

TWO ZEN CLASSICS

The Gateless Gate and the Blue Cliff Records

translated with commentaries by

K ATSUKI S EKIDA

edited and introduced by

A. V. G RIMSTONE

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2014

S HAMBHALA P UBLICATIONS , I NC .

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

Katsuki Sekida and A. V. Grimstone

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Two Zen classics: the Gateless gate and the Blue cliff records/translated with commentaries by Katsuki Sekida; edited and introduced by A. V. Grimstone.1st Shambhala ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: Weatherhill, 1995.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2556-7

ISBN 978-1-59030-282-8 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Huikai, 11831260. Wumen guan. 2. Yuanwu, 10631135. Bi yan lu. 3. Koan. I. Sekida, Katsuki, 18931987. II. Grimstone, A. V. III. Huikai, 11831260. Wumen guan. English. IV. Yuanwu, 10631135. Bi yan lu. English.

BQ9289.H843T94 2005

294.34432dc22

2005048966

CONTENTS

I N MY PREVIOUS BOOK , Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy , I tried to explain some aspects of the theory and practice of Zen in a way that would be intelligible to a contemporary Western reader. My approach in that book was deliberately not a traditional one but made use of current ideas in philosophy, psychology, and physiology. My reason for this was that I believe the time has come for Zen to move on from the positions in which it has been firmly entrenched for many years. However, I do not wish to imply that the classic teachings can now be set aside. Zen will no doubt develop, and perhaps in time new Zen literature will appear. It has not done so yet. Before any such development can take place, Zen students must master the traditional teachings. I have therefore translated the two famous texts Mumonkan and Hekiganroku and have tried, by supplying appropriate interpretive notes, to make them approachable to Western students of Zen. The general nature of these texts, and the ways in which they may be studied, are outlined in Dr. A. V. Grimstones introduction to this book.

I am deeply grateful to Dr. Grimstone, who, as with my previous book, has patiently turned my uncertain words into good English, written the introduction, and generally attended to all the problems involved in producing a book. The reader owes much to his labors. I must also thank most warmly Mr. Robert Aitken and Mr. Terence Griffin, who assisted me at an earlier stage with my translation of Mumonkan .

K. S.

T HE TEXTS TRANSLATED HERE by Katsuki Sekida, Mumonkan and Hekiganroku , are among the great classics in the literature of Zen Buddhism. They were composed in China in the Sung dynasty (9601279), and are the two best known and most frequently studied collections of koans. The aim of this introduction is to explain what manner of texts these are and to give the reader some indication of the ways in which they may best be approached. At the outset we should say that anyone beginning the study of Zen will find this book more readily comprehensible if Mr. Sekidas earlier book, Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy , has been read first.

Koans are a highly distinctive element in the literature of Zen Buddhism. There is no obvious parallel to them in the literature of other religions. They contain a message, but it is not a message that is expressed by way of direct instruction or exhortation. Case 30 in Hekiganroku , for exampleand it is a quite typical samplereads: A monk asked Jsh, I have heard that you closely followed Nansen. Is that true? Jsh said, Chinsh produces a big radish. An uninitiated reader perusing these texts would probably learn rather little about the nature of Zen Buddhist teachings. This is as we should expect, for in Zen each of us must arrive at his own directly experienced understanding. It cannot be transmitted to us by the words of others. The prime function of the koan is to serve as the medium through which this understanding may be reached. A koan is a problem or a subject for study, often, at first sight, of a totally intractable, insoluble kind, to which the student has to find an answer. This answer is not to be reached by the ordinary processes of reasoning and deduction. Indeed, to speak of an answer is perhaps inappropriate, since it suggests finding a solution to a problem by those methods. A koan is not an intellectual puzzle. We shall discuss shortly what it is and how it is to be approached, but to illustrate the point that a koan is no ordinary sort of problem we may note that the answer which is accepted by the students teacher may be as seemingly irrational as the koan itself: a word or phrase, or an action, which shows that the student has experienced for himself the element of Zen of which the koan treats. There is, too, no single, approved answer to a koan. What a teacher will accept as satisfactory depends on the student he is dealing with, the stage of progress of the students training, and so on.

Koans are by no means all of the same kind, as will probably be obvious to anyone who samples the ones in this book. Some are intended chiefly for the earliest stages in training, others for later ones. Case 1 of Mumonkan , for exampleJshs Muis the koan most commonly given to the beginning student, who has made some progress with controlling his thoughts by such preliminary exercises as counting or following the breath. Mu means nothing or nothingness, and ultimately, by dint of long practice, the Zen student comes to grasp this nothingness, but when he is actually working on this koan he is not directly contemplating or inquiring into nothingness, nor is he trying to decide whether or not the dog has Buddha Nature (which was the question that elicited Jshs Mu). He is using the word Mu, rather, as a meaningless sound on which to concentrate and with which to still his ordinary thought processes until he reaches the state of samadhi (see the notes to Mumonkan , Case 6). Some other koans are also used in these earliest stages of training. The majority, however, refer to later stages, when the student has attained some experience of samadhi, has achieved at least a preliminary sort of enlightenment, and is embarking on the long process of subsequent trainingthe cultivation of Holy Buddhahood, as it is calledwhich may lead him to maturity. Many koans deal with the application of Zen teaching to the ordinary situations of daily life. Koans have been classified into different types, relating to different aspects of Zen and their suitability for students at different stages in their training. It must be noted, too, that koans often contain layers of meaning that can be exposed by deeper and deeper study. A mature student returning to a koan may discover more in it than he did when he first studied it.

Next page