Published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

of Rutland, Vermont & Tokyo, Japan

with editorial offices at

Osaki Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032.

1959 by Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Inc.

LCC Card No. 59-8189

ISBN 978-1-4629-0224-8

editor's foreword

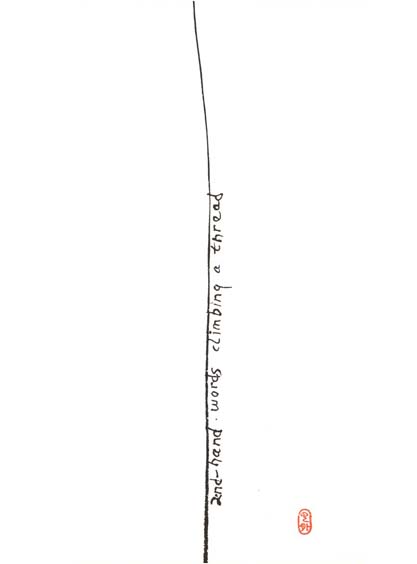

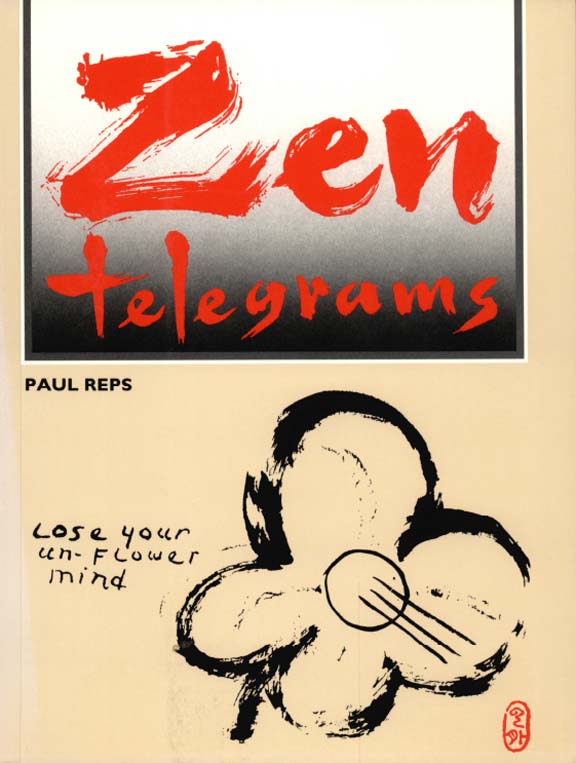

a book, like a life, must have a name. When Reps has to give a name to his picture-poems, he generally calls them "poems before words." But when I come to collect them into this book, I have chosen to call them "Zen telegrams."

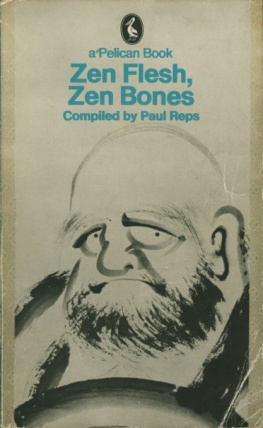

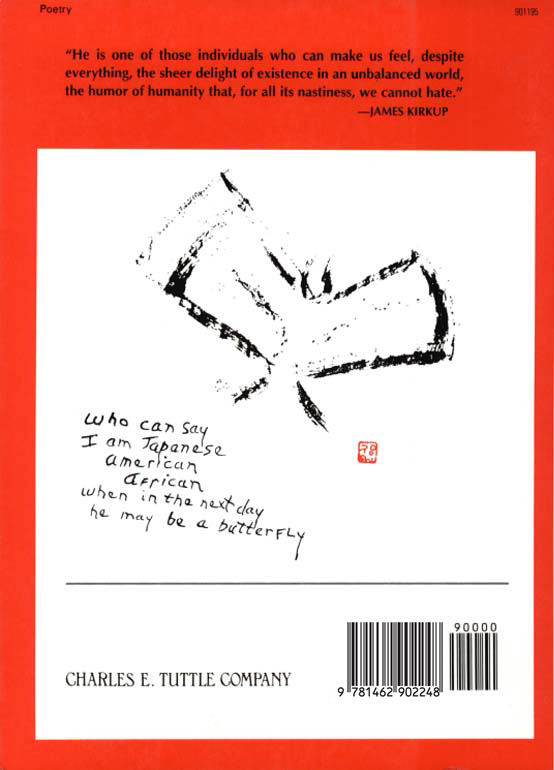

Reps never has labeled his picture-poems as Zen. "Zen," he has commented, "is a word I now almost never use. It is for children, for those innocent." Here he is speaking, and nowise disparagingly, of Zen as a formalized religion, a way of Buddhism that seeks-through "quiet sitting," meditation--the sudden flash of self-enlightenment that sets man free of earthly limitations, free of the need of words. But the word Zen has also taken on a wider meaning in recent years and is now often applied to a certain way of thinking, of aesthetics, of living. Reps himself has said: "Zen, cryptic as 'jazz,' is now a world word for God or Buddha in us shaking us alive after we've asked for it, earned it."

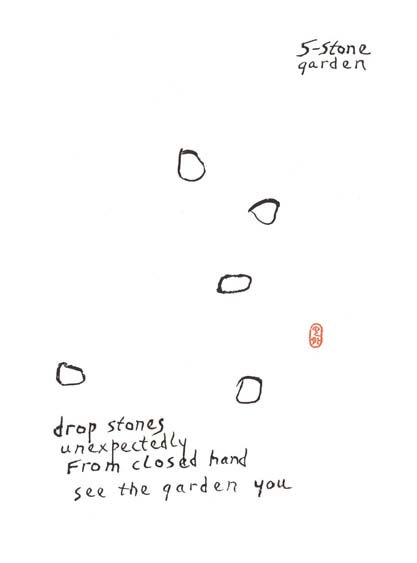

So it has seemed to me that his picture-poems glow with the unmistakable light that, for lack of a better word, may be most immediately described as this wider-meaning Zen. Certainly the label serves pointedly to say these picture-poems are akin to the Zen koan, to the shining instant the Zen masters evoked with these nonsensical conundrums that often made more "sense" than a library of philosophy. When Reps remarks that "poems before words intend to let the seer invite his originative life rhythm rather than having it imposed upon him," is he not saying Zen? is he not speaking as a long-time Zen familiar?

As for "telegrams," I have occasionally heard him call his picture-poems so. To me this seems exactly the word neededboth common enough and yet sharp enough to describe these communications that in intent are more than pictures, more than poems. If Zen is old, telegrams are very much of today. The juxtaposition of the two words points, then, to both the immediacy and the datelessness of what's here. If Zen works as a flash of insight, so do these. They do so telegraphically, freshly; they are not cast in the gone past. Who can resist opening a telegram?

When I once told him how much I liked a certain one of his pictures, Reps replied: "Tell me about the words, not the ink shapes!" For, as he has explained, the "ink shapes" are not for themselves but for giving another dimension to the words. In a sense, then, he is trying, through the medium of these shapes, to give the English word some of that pictorial, flashing quality which the ideographs of China and Japan possess in their own right, the quality that breathes magical life into their calligraphy. "Black brush lines on white space, such as calligraphy," he has observed, "are treasured by the Chinese and Japanese, who feel they receive something of the writer through them. They do not call them art. It is something from the heart."

And again: "Their calligraphy is picture writing. The character for man  pictures a man, field

pictures a man, field  looks like a field, and river

looks like a field, and river  shows as well as says river.

shows as well as says river.

becomes a three-picture poem, with each individual supplying his own detail and interpretation. Since eighty-five percent of our sensing comes through our seeing, picturing is primal poeming. With an alphabet language we are left straining to see, but not seeing, one step removed from the delight of a picturing way of thinking. Pictures are before words, in them, inclusive of them. Poems before words would see-say in this same care-less way and thus dip into primal vitality."

becomes a three-picture poem, with each individual supplying his own detail and interpretation. Since eighty-five percent of our sensing comes through our seeing, picturing is primal poeming. With an alphabet language we are left straining to see, but not seeing, one step removed from the delight of a picturing way of thinking. Pictures are before words, in them, inclusive of them. Poems before words would see-say in this same care-less way and thus dip into primal vitality."

Reps first started creating his picture-poems in Japan in 1952, using them as what he calls ''weightless gifts" and scattering them among his many friends, old and always new, as he moved about the world. In 1957 a Japanese poet friend to whom he had given a number of them started the first of the Reps picture-poem shows. In this Kyoto exhibit, as in all later ones, the poems, on rice paper of various sizes, were scotch-taped only at the tops to horizontal bamboo poles strung from the ceiling at different levels, and electric fans were made to blow them gently. There they fluttered like washing in the breeze, and the scene had somewhat the appearance of moving banners. There was also a sign that read:

1,000 yen each to automobile-owners

500 yen to well-dressed persons

200 yen to students

100 yen to anyone poor

10 yen to lovers of Buddha

"No one elected to pay ten yen," someone has observed, "so perhaps each loved himself more than Buddha." But thousands came to "read-see" and many stayed long. Each always seemed to find some particular one he liked for his own reasons, and Reps would give it to him or sell it at the price the buyer chose, and then draw another to hang in its place, sometimes the same one, sometimes a new one.

After that, Osaka wanted a show, then Tokyo, then Kyoto againand now I hear talk of Washington, Honolulu, Rome. The picture-poems were televised, newsreeled, radioed, written about, and even reproduced on silken obi in microscopic stitches of silk for elegant ladies. And his creating of the poems still continues, so that I've found myself with almost two hundred to choose from. To fit the space, I've had to winnow these down to seventy-nine, arranging them in four sections of sixteen each and one section of fifteen. The titles given in the table of contents are not formal titles but only key words that I've found convenient as memory aids.

pictures a man, field

pictures a man, field  looks like a field, and river

looks like a field, and river  shows as well as says river.

shows as well as says river.

becomes a three-picture poem, with each individual supplying his own detail and interpretation. Since eighty-five percent of our sensing comes through our seeing, picturing is primal poeming. With an alphabet language we are left straining to see, but not seeing, one step removed from the delight of a picturing way of thinking. Pictures are before words, in them, inclusive of them. Poems before words would see-say in this same care-less way and thus dip into primal vitality."

becomes a three-picture poem, with each individual supplying his own detail and interpretation. Since eighty-five percent of our sensing comes through our seeing, picturing is primal poeming. With an alphabet language we are left straining to see, but not seeing, one step removed from the delight of a picturing way of thinking. Pictures are before words, in them, inclusive of them. Poems before words would see-say in this same care-less way and thus dip into primal vitality."