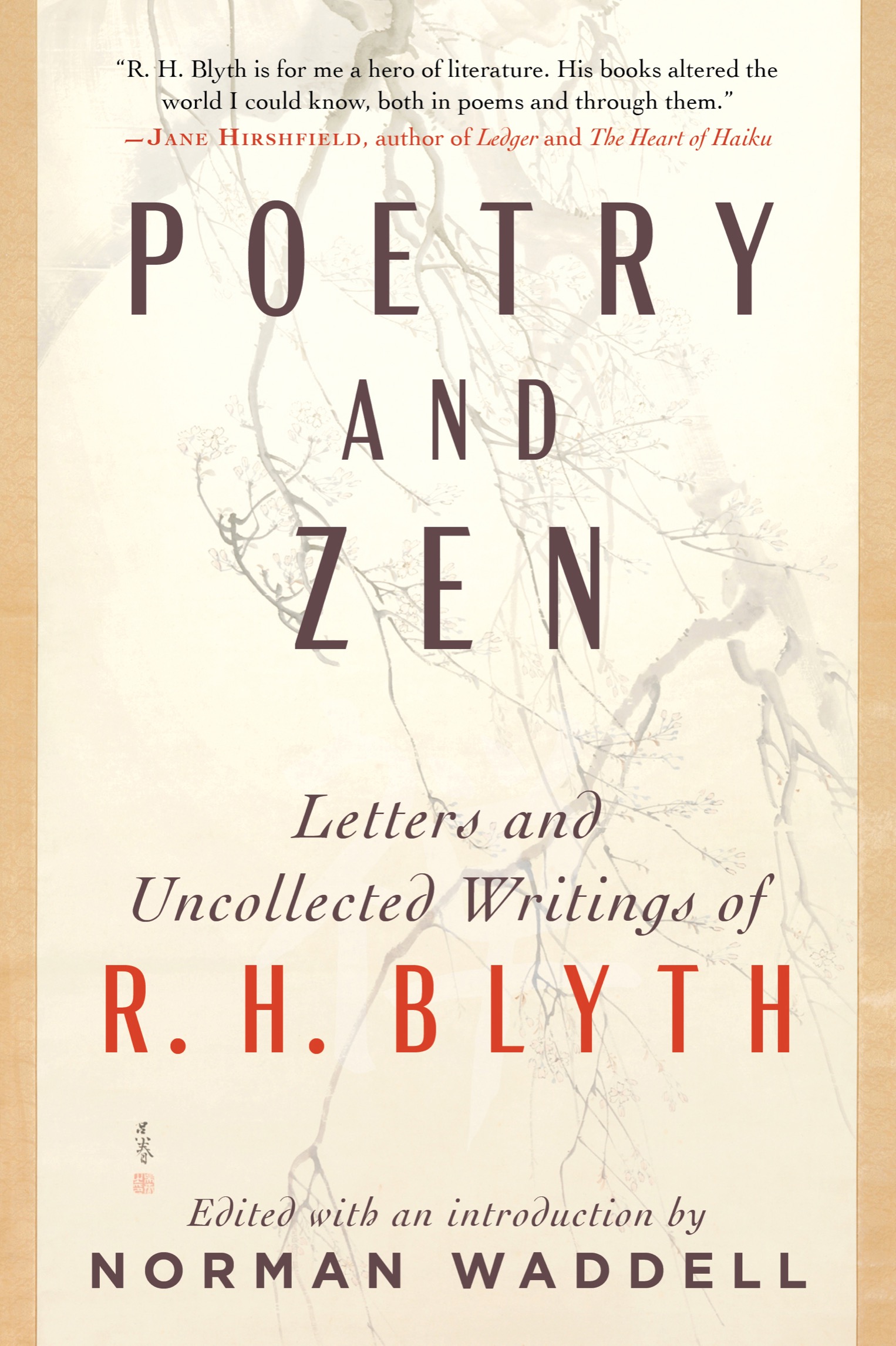

ADDITIONAL PRAISE

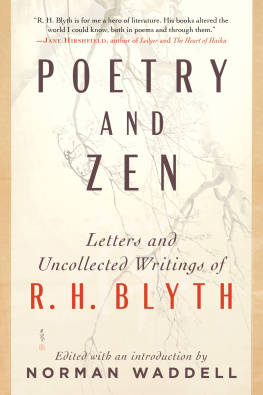

In high school, R. H. Blyths four-volume Haiku was the first book on Japan I read. Together with his books on senry and his translation/commentary on Mumonkan, I have continually reread them for inspiration and pleasure and relied on them as valuable references. I knew little about the man himselfnobody did in those days. Fortunately, Poetry and Zen finally fleshes out the life of this eccentric scholar. The book also provides the background for the remarkable internationalization of Zen in the second half of the twentieth century. On all fronts, Poetry and Zen is an enjoyable read.

John Stevens, translator of The Art of Peace

Blyths previously unpublished writings are reason enough to purchase this book. A second reason its quality of the writing. One aspect that Blyth found vital in haiku and senry is humor, which he called the dance of life. His essays back up this claim, making reading them a pleasure. Along the way, Blyth compares haiku to senry, to mysticism, to Zen, to Western literature, to Christian texts, to Buddhism, and to Western humor, to name a few. He also writes about Suzuki and Aitken, bringing new light to their notable Zen lives and teachings. For anyone who has not read Blyth, a treat awaits you. And for those who have, there is much more still to enjoy.

Stephen Addiss, author of The Art of Zen

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

2129 13th Street

Boulder, Colorado 80302

www.shambhala.com

2022 by Norman Waddell

Cover Art: Cherry Blossoms The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975

Cover Design: Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Interior design: Katrina Noble

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blyth, Reginald Horace author. | Waddell, Norman, editor.

Title: Poetry and Zen: letters and uncollected writings of R. H. Blyth / edited with an introduction by Norman Waddell.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Shambhala, 2022.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021026481 | ISBN 9781611809985 (trade paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Blyth, Reginald HoraceCorrespondence. | CriticsJapanCorrespondence. | CriticsEnglandCorrespondence. | Buddhist scholarsJapanCorrespondence. I Buddhist scholarsEnglandCorrespondence. | HaikuTranslating into English. | HaikuHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PL713.B69 A25 2022 | DDC 828/.91209dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021026481

Ebook ISBN9780834844223

a_prh_6.0_139653422_c0_r1

CONTENTS

EDITORS PREFACE

Most of the material in this book was originally assembled over fifty years ago when I was compiling a volume of R. H. Blyths miscellaneous writingsarticles and essays that had appeared in magazines and journals, book reviews, introductions written for student textbooksfor his publisher Hokuseido Press in Tokyo. I was working with Nakatsuchi Jumpei, president of Hokuseido Press, contemplating something along the lines of D. H. Lawrences Phoenix (1936), although I wanted it to include a selection of letters as well. In the course of the project, I made the acquaintance of two of Blyths closest friends, his cousin Dora Lord (Dora Orr after her marriage in the 1950s) and Robert Aitken. They both readily agreed to help, kindly providing encouragement and numerous insights into Blyths personal life and copies of the letters they had received from him. Dora even included a group of letters to Blyths parents that his mother, Hetty, had entrusted to her. The letters to Dora were of special importance since they provided virtually the only record of Blyth and his daily life during the prewar period (19291940) when he was teaching in Korea, a period that has hitherto been virtually a blank.

When I began the project in the late 1960s, his booksalmost all of them published by Hokuseido Presshad very poor distribution in the West. Blyth himself was perfectly happy with that arrangement. In a letter to Nakatsuchi Jumpei, Blyth wrote that having him as a publisher was one of the (few) luckiest things in my life. I dont want to make any money. I only want to write books and eat. To write excellent books is my greatest pleasure. The second is to have you as my publisher. He often stated that one good reader was enough for him.

Nonetheless, one of my aims in compiling the original miscellany was to make Blyth better known overseas, in America and continental Europe. It seemed to me that the best way to draw attention to the book would be to induce one of his well-known admirers in the American artistic community to contribute a foreword. I knew from Blyths letters that he had corresponded with the novelist J. D. Salinger, so I wrote Salinger, told him about the proposed book, and asked if he would consider writing an introduction.

I felt fairly sure that Salinger had never written such a foreword before and had no great hopes of even receiving an answer. But answer he did, quite promptly, and in a kind, warmhearted manner. I cant tell you what his books have meant to me, he wrote. The idea of a miscellany interests me very muchFor a first posthumous bookit seems to me right to show Blyth first, away from his beloved haiku, at his miscellaneous best. His readiness to agree to write the foreword was, of course, extremely encouraging, but, as the Chinese say, Many things have good beginnings; few reach a successful end.

It was over a year later, August 1968, when Salingers next letter arrived. He apologized for failing to write earlier, saying that the past year had been an unquiet one for him: Im very sorry. Blyth surely deserves something or someone better and zennier. But as he also said in ending the letter that he would no doubt be pulling [himself] together within the year, and I was as convinced as ever that he was the right person for the job. I decided to wait a bit longer and give things a chance to work themselves out.

There was, however, no word for another year or more. By this time, though still harboring hopes for an introduction, I began to get caught up in other priorities, teaching and translating. The project fell by the wayside, and I had no further contact with Salinger for more than twenty years.

Although I had packed the material away, the idea of the miscellany was never completely out of mind. I mulled over one other piece of advice Salinger had given, against including Blyths letters in the book. He objected as a matter of principle to publishing a writers letters unless the writer himself had authorized it. Later, in the 1990s, when I got to know him personally, he was even more adamant on this point, perhaps as a result of the widely reported troubles he had recently gone through concerning the publication of his own letters. In any case, there was no reason to press the point any further, and that is how the matter ended.

The boxes were still on a back shelf in 2011, forty years later, when I was invited to give lectures on the Suzuki-Blyth relationship at a memorial library dedicated to Blyths mentor Daisetz Suzuki. I brought the boxes out and combed through the material once again, thinking it would jog my memory. In reading through the letters, it didnt take long for me to see, with much greater clarity than before, the importance of getting them published, if only for the valuable firsthand information they contained about the role Blyth played in the immediate postwar period, when the Imperial system, the Japanese government, and society itself were undergoing drastic and fundamental change.