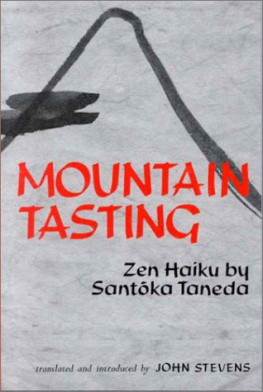

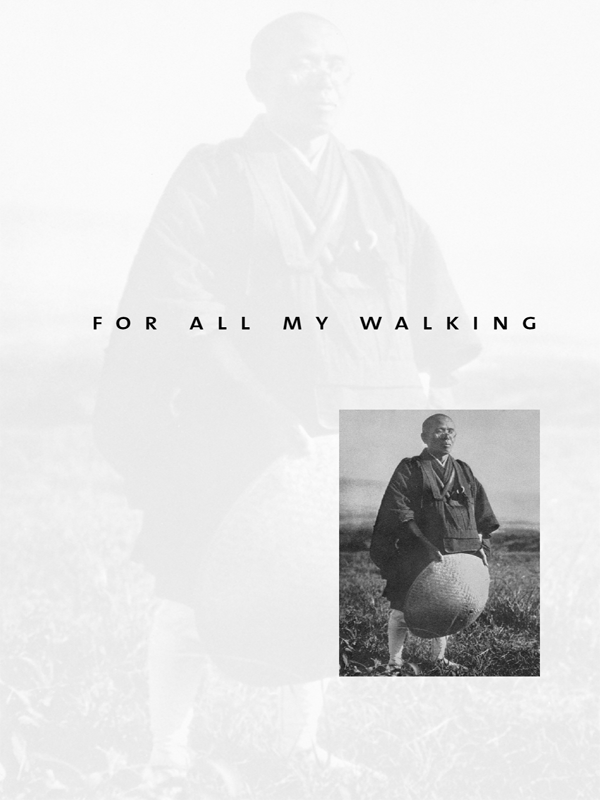

FOR ALL MY WALKING

Modern Asian Literature

Translated by Burton Watson

Free-Verse Haiku of Taneda Santka

with Excerpts from His Diaries

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50063-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taneda, Santoka, 18821940.

[Poems. English. Selections]

For all my walking : free-verse haiku of

Taneda Santoka with excerpts from his diaries /

translated by Burton Watson.

p. cm.(Modern Asian literature series)

ISBN 023112516X (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0231125178 (paper : alk. paper)

I. Watson, Burton, 1925II. Taneda,

Santoka, 18821940. Nikki. English. Selections.

III. Title. IV. Series.

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Contents

1882 | DECEMBER 3. Born in Nishisabary, Yamaguchi Prefecture |

1892 | Mother commits suicide |

1902 | Enters Department of Literature at Waseda University in Tokyo |

1904 | Withdraws from Waseda and returns to Nishisabary |

1906 | Father goes into sake-brewing business |

1909 | Marries Sat Sakino of neighboring village |

1910 | Son, Ken, is born |

1913 | Becomes follower of Ogiwara Seisensui Begins publishing free-style haiku in Son (Layered Clouds) |

1916 | Sake brewery fails

With wife and child, moves to Kumamoto, in Kyushu |

1918 | Younger brother, Jir, commits suicide Grandmother dies |

1919 | Goes to Tokyo alone and works at various jobs |

1920 | At request of wifes family, is divorced from wife |

1921 | Father dies |

1923 | After Great Kanto Earthquake, returns to Kumamoto |

1924 | Attempts suicide (?) by standing in front of trolley, and is put under the care of Mochizuki Gian, a priest of Zen temple Hon-ji in Kumamoto |

1925 | Becomes ordained Zen priest and is put in charge of Mitori Kannon-d |

1926 | Sets off on three-year walking trip through Kyushu, Honshu, Shikoku, and Shodjima |

1929 | Returns to Kumamoto, but sets off on more walking trips |

1932 | Moves into small cottage called Goch-an in Ogri, Yamaguchi Prefecture |

19331938 | Lives in cottage, supported by friends; takes occasional trips; and publishes several small collections of poems |

1938 | Late in year, moves to Yuda, Yamaguchi Prefecture |

1939 | Takes walking trip in Shikoku

Late in year, moves to cottage in Matsuyama, in Shikoku |

1940 | APRIL . Publishes collection of poems, Smokut (Grass and Tree Stupa)

OCTOBER 11 . Dies in sleep in cottage in Matsuyama |

The brief poetic form known today as haiku enjoyed immense popularity in Japan during the Edo period (16001867), when poets such as Bash and Buson produced superlative works in the genre and a craze for haiku writing spread through many sectors of the population. But by the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the beginning of Japans modern era, the form had sunk to a very low level of literary worth, being marked mainly by stale imitations of the past or facile wordplay or satire, often of a vulgar nature.

In the early years of the Meiji period, the poet and critic Masaoka Shiki (18671902) succeeded in injecting new life into the form and restoring it as a vehicle for serious artistic expression. Since his time, the writing of haiku has constituted an integral part of the Japanese literary scene, and in recent years the form has been taken up by poets in many other countries and languages as well.

Although Shiki greatly broadened the subject matter of the haiku and employed a more colloquial diction, he continued to write in the traditional form, which uses seventeen syllables or sound symbols arranged in a 575 pattern and invariably includes a kigo (season word) that indicates the particular season in which the poem is set.

Shiki had two outstanding disciples in the art of haiku composition: Takahama Kyoshi (18741959) and Kawahigashi Hekigot (18731937). Kyoshi, writing in the traditional haiku form as Shiki had, produced during his long life a large body of works that has been highly esteemed by Japanese critics. Hekigot, on the contrary, in time grew dissatisfied with the formal requirements of the traditional haiku and began experimenting with the writing of what are now known as free-verse or free-style haiku, brief poems that do not adhere to the 575 sound pattern and do not regularly include a season word.

This new free-style haiku form was originated by one of Hekigots disciples, Ogiwara Seisensui (18841976). And Taneda Santka, whose free-style haiku are the subject of this volume, was a disciple of Seisensui. Thus, in the kinship terms so beloved by Japanese critics, Taneda Santka was a literary grandson of Kawahigashi Hekigot and a great-grandson of Masaoka Shiki.

Although Santka wrote conventional-style haiku in his youth, the vast majority of his works, and those for which he is most admired, are in free-verse form. He also left a number of diaries in which he frequently records the circumstances that led to the composition of a particular poem or group of poems. His poetry attracted only limited notice during his lifetime, but in recent years in Japan there has been a remarkable upsurge of interest in his life and writings. His complete works were published in seven large volumes in 1972 and 1973, and Japanese bookstores now customarily display an impressive array of Santkas poems, letters, and diaries, as well as critical studies and memoirs by persons who knew him.

As Ivan Morris noted some years ago in The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, the Japanese have a marked fondness for people who in one way or another have made a mess of their lives. And, as we will see when we come to a discussion of Santkas biography, he was a prime example of the messy type. Much of the popularity that his works now enjoy is due to their undoubted literary worth, but much of it is also attributable to the highly unconventional and in some ways tragic life he led. His poetry and his life demand to be taken together.

Taneda Santka, whose childhood name was Shichi, was born on December 3, 1882, the elder son of a well-to-do landowner in Nishisabary, in what is now part of Hfu City in Yamaguchi Prefecture. He had two sisters and a younger brother. His father seems to have been a rather weak-willed man who spent his time dabbling in local politics, chasing after women, and in general dissipating the family fortune, which had been of considerable size at the time he fell heir to it.