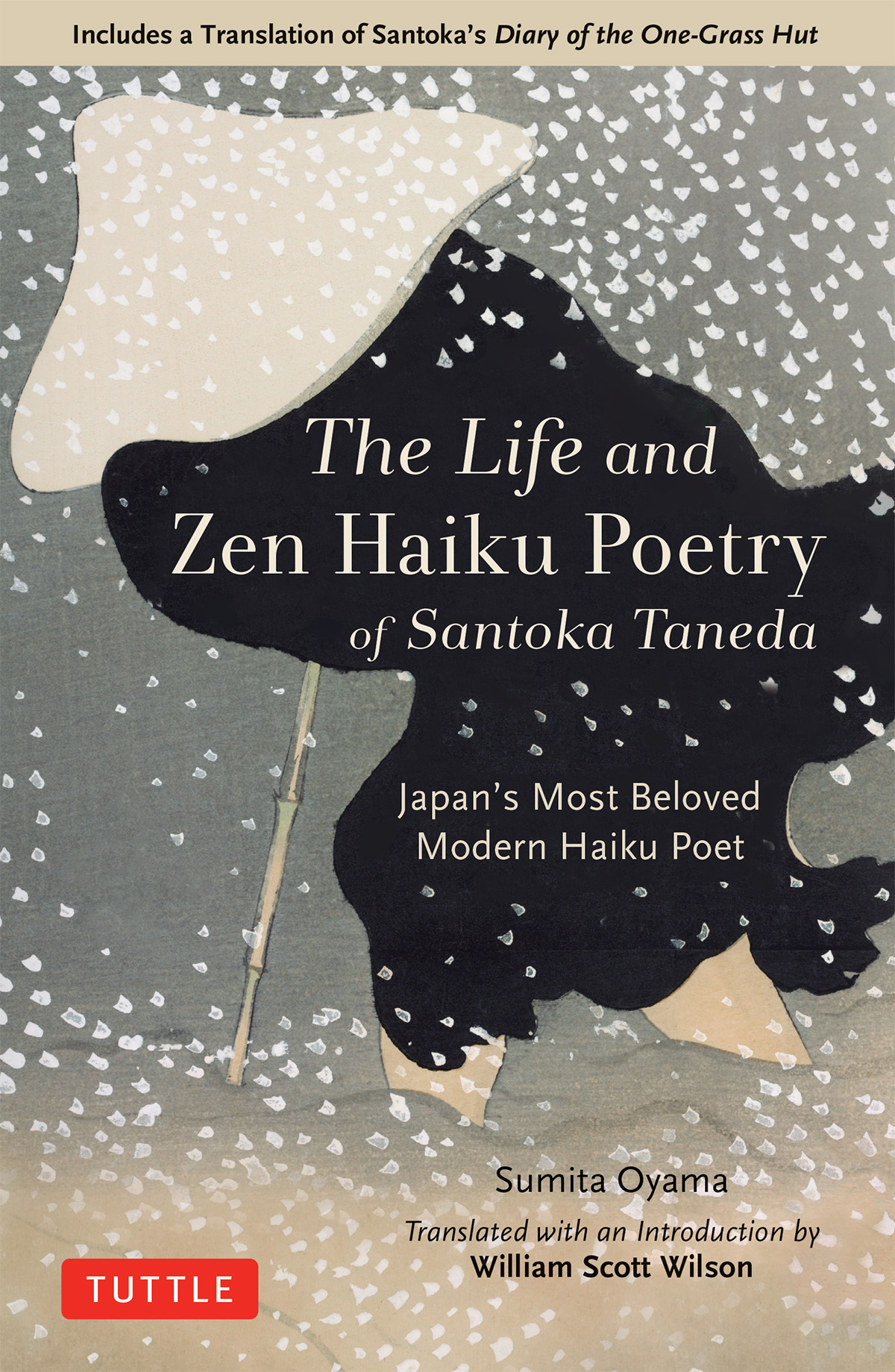

Sumita Oyama - The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda

Here you can read online Sumita Oyama - The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Tuttle Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda

- Author:

- Publisher:Tuttle Publishing

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Life and

Zen Haiku Poetry

of Santoka Taneda

This translation is dedicated to Robin D. Gill.

Sumita Oyama (18991994) was born in Okayama Prefecture, Japan. He practiced haiku and Zen for over sixty years. He was a prolific writer, publishing many books on the haiku poet Santoka Taneda. Oyama was a good friend and benefactor of Santoka, and studied free haiku under the poet Seisensui Ogiwara.

William Scott Wilson has published more than twenty books that have been translated into more than twenty foreign languages. His first book, a translation of Hagakure, an eighteenth century treatise on samurai philosophy, was featured in the film Ghost Dog, directed by Jim Jarmusch. He was awarded a Commendation from the Foreign Ministry of Japan in 2005 and inducted into the Order of the Rising Sun in 2015.

Prologue

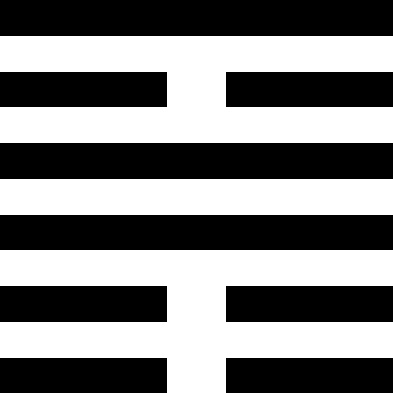

The fifty-sixth hexagram of the ancient Chinese divination text, the I Ching is Lu, defined as journey, travel or traveler. It is composed of two trigrams: fire and mountain. The lower trigram, mountain, is explained as signifying good, stopping, or looking backward. Its virtue is stopping in peace. The upper trigram, fire, is defined as separation, or possibly nightingale. Its virtue is bright wisdom. Thus, fire over the mountain.

Exactly when or why Santoka took his pen name, which is literally Fire on the Head of the Mountain (), is unclear, but it was a prescient choice, as he would spend most of his life after the age of forty traveling, saying goodbye to his friends, looking back on his character, and composing haiku, much like the elusive nightingale, which is sometimes heard but rarely seen.

According to the I Ching, if the traveler is steadfast, he will meet with good fortune; and with timing and faith, he will become great. Certainly, Santokas personal life was a mess, but through perseverance and faith in his only abilityto write poetrythis lonely traveler lit up the Japanese literary sky like a fire over a mountain.

Preface

Those who do not know the meaning of weeds, do not know the mind of nature. Weeds grasp their own essence and express its truth.

Santokas diary, August 8, 1940

This book portrays the life of the haiku poet and Zen priest Santoka, a man who could well identify with weeds: unruly, unkempt, taking sustenance from wherever he could find it, and inexorably expressing his own truth with the small irregular blossoms of what might be called free haiku. Like a weed, he was inimical to restraintin both his life and poetry, which he accounted for as indivisible. We have to explain ourselves, not control ourselves, he wrote.

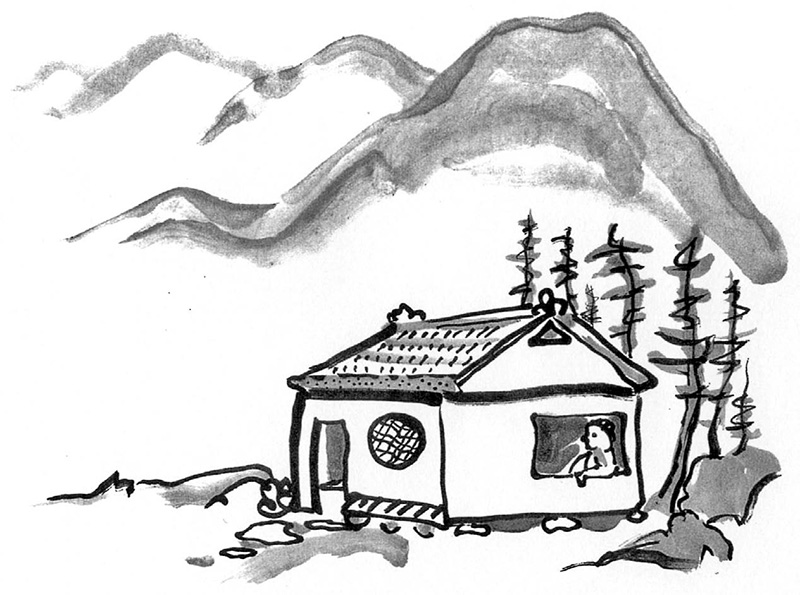

As a responsible human being, Santoka was hopeless. Having left his wife and child, he suddenly became a Buddhist priest. Unable to stay in the confines of a temple, he hit the road. When not on the road or staying over at someones house, he lived in small huts paid for by his friends and apprentices. One of these hermitages was finally so broken down that his biographer punned that it might have been called the home of a haijin () or abandoned person, rather than that of a haijin (), or haiku poet. He was sometimes found so drunk that he could only make it back to his hermitage with the help of a friendly neighbor. By his own admission, he was incapable of really doing anything other than wandering on his own two feet and writing his own verses. These two, with his Buddhist vows and a hopeless love of sake, made up the karma he was determined to follow through.

I first became interested in Santokas eccentric, generally technique-less poetry during the late 1960s, reading through R. H. Blyths History of Haiku, while living in a small village in Mino, Japan, in a thatched hut not much better, I think, than Santokas Gochu-an hermitage. Built around the year 1700, it was a typical traditional peasants house with walls of clay and straw, and a roof of thick miscanthus thatch. With low mountains almost up to the front yard and a small Buddhist temple across the nearby stream, it seemed the perfect place to absorb the material I was reading. During the rainy season, as I daily rearranged the pots collecting the rainwater dripping through the thatch, Santokas haiku were never far from mind.

My rainhats

leaking

too?

Not long afterward, I discovered a copy of Sumita Oyamas Haijin Santoka no shogai (Life of the Haiku Poet Santoka) also translated in the appendix to this book. This short, three-month diary contains the poets views on everything from writing verse to cooking rice, his anxieties about his inability to live an ordered life, and a number of wonderful short anecdotes concerning his last days. Together, these two works give a fuller image of this mostly wandering shabby manonce a literary prodigy in collegewalking through the fields and back roads of Japan, looking under hedges for some shy wild flower, and always finding, as was his wont, himself.

Sumita Oyama (18991994) was one of Santokas greatest friends and benefactors. A minor government official, an educator and a serious student of Zen Buddhism, he was also a prodigious author, writing books and articles on Far Eastern philosophy, on literary figures such as Basho, Ryokan and Toson Shimazaki, and, a miscellany of his own country in his book Nihon no aji (A Taste of Japan). He lived the latter part of his life in Matsuyama on the island of Shikoku, not far from Santokas last hermitage, the One-Grass Hut.

There are always a number of people who have given their help, either editorially or spiritually, consciously or unconsciously, in any one work. For this one volume, it must be stated first that the translation itself would have never been possible without the extraordinary generosity of my late friend, Takashi Ichikawa, who provided me at his own cost with many of the works in the original listed in the bibliography. He was a benefactor and mentor beyond compare. A special thanks to Ms Yasuko Imai, who also helped with providing me with books hard to obtain. I would also like to thank those friends who have encouraged and spiritually supported me over the years, and especially concerning this project: Kate Barnes, Gary Haskins, Jim Brems, John Siscoe, Jack Whistler, Dr. Daniel Medvedov, Dr. Justin Newman, Tom Levidiotis, Bill Durham Roshi, Professor Steven Heine, and especially my wife, Emily, who has patiently proofread this and other of my manuscripts over the years. To my late professors, Noburu Hiraga and Richard McKinnon, I owe a deep bow of thanks for all they tried to teach me concerning every aspect of Japanese language and culture. I also owe a special debt of gratitude to Sean Michael Wilson, Barry Lancet, Prof. Masako Kubota, Nanae Tamura, Terufusa Fujioka, Yasuhiro Ota, and Tsurugi Takata for helping me find the places so important to Santoka in Kyushu and Shikoku; and to my editor at Tuttle Publishing, Cathy Layne, who has patiently seen this project through to the end. Finally, I am profoundly grateful to Masakaze Oyama, who kindly gave us the rights to translate and publish his fathers book in this English translation.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

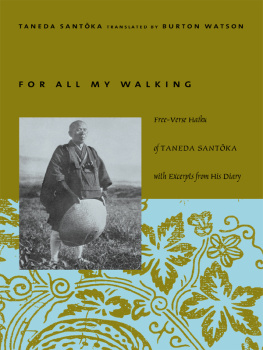

Similar books «The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda»

Look at similar books to The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Life and Zen Haiku Poetry of Santoka Taneda and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.