English Romantic Verse

INTRODUCED AND EDITED BY

David Wright PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England www.penguin.com First published 1968

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 1986

32 Copyright David Wright, 1968

All rights reserved Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser EISBN: 9781101491263

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

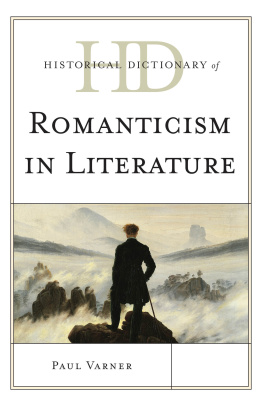

What used to be called the Romantic Revival in English poetry was sometimes reckoned to have begun with the publication of

Lyrical Ballads in 1798 and to have more or less ended with the death of Byron in 1824. By then Shelley and Keats were dead, and Wordsworth and Coleridge mainly silent. Since most English poetry labelled Romantic which includes some of the best English poetry ever written belongs to this period, that view was tenable, convenient, and misleading. For the Romantic Movement manifested itself before Wordsworth and Coleridge collaborated to produce

Lyrical Ballads, and went on long after Byron died at Missolonghi.

Under many and various metamorphoses it may even be said to have continued to our own day. The term Romantic obfuscates. It asks for comparison, always partisan, with its mirror-image, the Classical; the first being seen as the antithesis of the second. A ding-dong battle so far as writing about writing is concerned has gone on between Romantic and Classical. This debate is really a side-issue perhaps it would not be too much to claim that the Classical is an essentially Romantic concept largely introduced, so far as England is concerned, by Matthew Arnold. The glosses given to the two epithets have been many and confusing.

They have become, as often happens in the field of literary criticism and poetic theory, terms of abuse. But generally the Romantic is held to signify the daemonic, subjective, personal, irrational, and emotional; the Classical to indicate whatever is objective, impersonal, rational, and orderly. Klassisch ist das Gesunde, romantisch das Kranke, All of which is true enough if one is thinking chiefly of what Wyndham Lewis calls the extremist wing of Romanticism to which Professor Mario Praz devoted a good deal of his well-known book, The Romantic Agony. Too much value has been given to the Romantic decadence, just as too much attention has been paid to the more obvious and vulgar manifestations of the Romantic sensibility its gothic sensationalism and its later cult of the horrible. When these largely secondary symptoms of Romanticism are contrasted with an opposing temperament called Classical much of the real significance of the phenomenon known as the Romantic Movement goes out of the window. And when Professor Grierson in his lecture Romantic and Classical goes back it would seem to the very beginning of western culture to claim Plato and St Paul as the first Romantics, against Aristotle as the first Classical, the line-up of the two teams becomes a game: e.g. Shakespeare is Romantic, Ben Jonson Classical; or if you like, Marlowe is Romantic, Shakespeare Classical, and so on ad infinitum.

Which is to miss the point. Romanticism is a historical phenomenon that should be approached as such. When did it begin? The word romantic itself dates from the middle of the seventeenth century. The revolutionary character of the 1650s might almost be demonstrated from the history of one word the word romantic, writes F. W. Bateson in English Poetry. He goes on: Until 1650 no need seems to have been felt for an adjective for the common word romance.

But between 1650 and 1659 the word romantic is used by no less than seven writers. On most of these occasions the word would seem to have been an independent creation. Now, as Eliot remarked in a famous essay, it was in the seventeenth century that a disassociation of sensibility from which we have never recovered set in. The language became more refined, the feeling more crude, he says. The feeling, the sensibility expressed in The Country Churchyard (Gray) is cruder than that in To his Coy Mistress (Marvell). The sentimental age begins early in the eighteenth century.

What Eliot noted was the first symptoms of a difference in outlook which separates the modern from what for want of a better term one may call the pre-Newtonian sensibility.when he has been pushed to the periphery of an illimitable and apparently expanding universe. That is to say, it was the spiritual and metaphysical implications of the scientific and technological revolution which began in the seventeenth century and which was going at full throttle by the end of the eighteenth, together with the changed and changing view of mans place in the universe, that sparked off the Romantic Movement. In other words, the more sensitive and serious intelligences, which usually turn out to belong to poets and artists the antennae of the race in Pounds phrase began to react, and in most cases to record disquiet. The Romantic Movement, if we are to understand what it really was about, should be viewed in its relation to the Industrial Revolution and its consequences. There was in fact no such thing as a Romantic revival. It was rather a birth of a new kind of sensibility which had to do with the new kind of environment that man was in the process of creating for himself.

If the individual was on the way to being regimented, then poets and artists, with as it were intuitive prescience, began to seek to balance the scale by giving the greatest value to individual consciousness. In doing so they exalted Imagination as the noblest of human faculties. In parenthesis, one reason why the French Revolution of 1789 was a central experience to Romantic poets is that they saw it as essentially a revolution to emancipate the individual. The outward form of the inward grace of the Romantic imagination was the French Revolution, and the Revolution failed. the two key poems to the Romantic sensibility were begun about the same time; some of Coleridges poem may have been written partly as an answer to Wordsworths. The interaction of the two poems on one another is illuminating.

ENGLISH ROMANTIC VERSE DAVID WRIGHTS Selected Poems appeared in 1990 and his Collected Poems after his death in 1994. He edited The Penguin Book of Everyday Verse, Longer Contemporary Poems, Thomas Hardy: Selected Poems, Edward Thomass Selected Poems and Prose, Trelawnys Records of Shelley, Byron and the Author, Thomas Hardys Under the Greenwood Tree and De Quinceys Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets for Penguin. He translated Beowulf and The Canterbury Tales, and published an autobiography entitled Deafness.

ENGLISH ROMANTIC VERSE DAVID WRIGHTS Selected Poems appeared in 1990 and his Collected Poems after his death in 1994. He edited The Penguin Book of Everyday Verse, Longer Contemporary Poems, Thomas Hardy: Selected Poems, Edward Thomass Selected Poems and Prose, Trelawnys Records of Shelley, Byron and the Author, Thomas Hardys Under the Greenwood Tree and De Quinceys Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets for Penguin. He translated Beowulf and The Canterbury Tales, and published an autobiography entitled Deafness. INTRODUCED AND EDITED BY

INTRODUCED AND EDITED BY