To

Leslie David for the utter wonde of passing and becoming

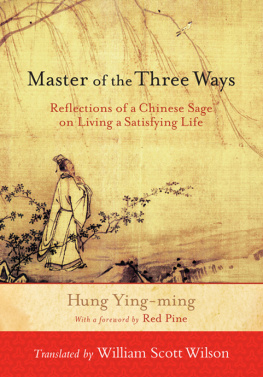

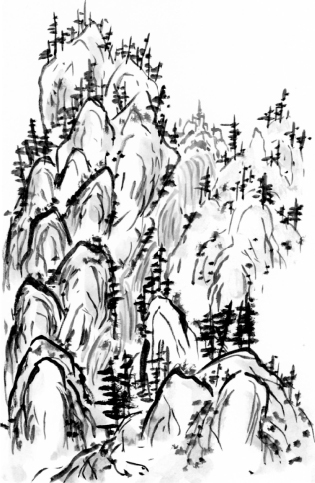

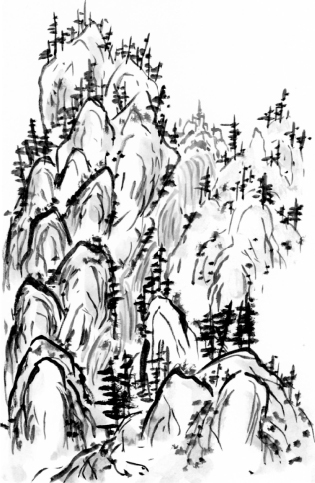

Acknowledgement for Illustrations: William Gaetz has been an accomplished vocalist, classical pianist, philosopher and photographer. But his life-long interest in the creative process and the sophisticated discipline of Zen led him to study Chinese brush painting under the tutelage of Master Professor Peng Kung Yi. He has since become a master of this technique, with works hanging in homes and businesses throughout Canada and the United States. His paintings, sold under his Chinese name Koy Sai, are still available through local galleries and from his studio in Victoria, British Columbia. The Sages Way is the fifth book by Ray Grigg that William Gaetz has illustrated. In this instance, Mr. Gaetz uses the elegant and rustic simplicity of traditional Chinese brush painting to match the grounded and earthy character of The Sages Way. The author deeply appreciates Mr. Gaetzs generous contribution to this book.

The Sages Way

Teachings & Commentaries

Ray Grigg

Copyright 2004 Ray Grigg. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

All ink drawings are 2004 by William Gaetz and are reproduced by kind permission of the artist.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

A cataloguing record for this book that includes the U.S. Library of Congress Classification number, the Library of Congress Call number and the Dewey Decimal cataloguing code is available from the National Library of Canada. The complete cataloguing record can be obtained from the National Librarys online database at: www. nlc-bnc.ca/amicus/index-e.html

ISBN: 1-4120-2168-5

ISBN: 978-1-4122-2129-0 (eBook)

This book was published on-demand in cooperation with Trafford Publishing.

On-demand publishing is a unique process and service of making a book available for retail sale to the public taking advantage of on-demand manufacturing and Internet marketing. On-demand publishing includes promotions, retail sales, manufacturing, order fulfilment, accounting and collecting royalties on behalf of the author.

Suite 6E, 2333 Government St., Victoria, B.C. V8T 4P4, CANADA

Phone 250-383-6864 Toll-free 1-888-232-4444 (Canada & US)

Fax 250-383-6804 E-mail

Web site www.trafford.com

TRAFFORD PUBLISHING IS A DIVISION OF TRAFFORD HOLDINGS LTD.

Trafford Catalogue #03-2717 www.trafford.com/robots/03-2717.html

10 9876543 2 1

Contents

The same narrow path still leads from the village of Chang-an in the Wu Valley, crosses a footbridge over the Han River, then wanders through a rough flatland of scattered pines and broken boulders. Beyond the fork to the Kai-tung Monastery, it begins winding upward between great outcroppings of rock, carefully searching its way to the Tien-po Temple at the base of Mount Shan. Here the path ends and the mountain towers skyward, tumbling toward the sun and moon in huge heaving masses of stone. And the people of Chang-an still believe that special powers reside on this mountain because it is so close to Heaven.

High on Mount Shan, the villagers still say, grows a hidden forest of ancient trees where twisted branches breathe the clear air of wisdom and gnarled roots drink the calm of cool water. And all agree that a sage once lived in this secret place between Heaven and Earthindeed, may even have visited their village. But no one had ever met this mysterious sage of Mount Shan. And no one had ever ventured beyond the temple to find him, for all asserted they were too busy with the affairs of ordinary life to climb such a mountain in search of such a person.

Old Shu, who was often wandering through the village and along the paths of the valley, said he had never encountered this mysterious sage of Mount Shan. Nevertheless, the villagers insisted that such a sage must exist. Who else, they reasoned, could bring the good fortune that had blessed Chang-an? The seasonal rhythms of weather had welcomed both planting and harvesting, the fields of the Wu Valley had been bountiful, even the catches in the Han River had been generous. So the passing of their lives, without the famines and wars of earlier years, had assumed a natural and ordered grace. In brief, they contended, the harmony of Heaven that pervaded their village and valley was testament to the influence of a sage.

Indeed, only the presence of a sage could account for the ragged manuscript that was found beside the path near the Tien-po Temple. Although no one could agree whether the writings were old or new, no one could doubt that such a find confirmed that a sage was living among them. So, in the comfort of a confidence that arose from unquestioned conviction, the people speculated and imagined who this sage might be.

Once, during a gathering on a Chang-an street, one man even joked that Old Shu might be this mysterious sage of Mount Shan. The other men laughed uproariously at the obvious absurdity. Old Shu himself flashed a broad grin, his eyes shining and dancing as he cocked his head sideways to look up at their mirthful faces. The mature women in the gathering just smiled with polite restraint. Other women shuffled awkwardly at the questionable humour. But the younger villagers, too unschooled in social proprieties to control themselves, giggled openly at the suggestiona suggestion that would not have been so comical if Old Shu had not seemed so confused and forgetful, so lost and different. Or, perhaps, if he had not looked so strange.

Old Shu was a hunchback. His shoulders towered above his head, his neckbone pointed to the sky and his chin rested on his belly button. His bent and twisted body was a disordered heap of flesh and bonesribs draped over hips, vital organs hanging upside-down, hands dangling beside his feet.

Despite this condition, he managed well enough. With eyes so close to the ground he found useful things to trade and sell. By weeding gardens and gathering firewood, he earned a few extra coins. From harvested fields, he gleaned a little grain for his winter stores. During famines, he was given extra rations of rice because the government officials thought he was crippled and helpless. When wars broke out, he was never conscripted because the passing armies considered him unfit and useless. My twisted body has adjusted to itself, he once said, and I have accepted its strangeness. By learning to live with myself, I have learned to live with the world. And by knowing myself, I have found more than myself.

Old Shu said many things but the villagers did not usually listen. Sometimes they found him difficult to understand because he talked about subjects that did not interest them. Sometimes he made no sense at all, as if his thinking had become as peculiar as his body. Other times he was strangely silent. Or he wandered away and no one saw him for days.

So the people of Chang-an decided that Old Shus mind was also bent and twisted, as upside-down as his organs. They listened politely when he spoke. They treated him with patience and tolerance, with the bemused respect accorded to his age and condition. But they did not take him seriously. And they did not hear what he had to say. Besides, when all was well in their village and valley, when they were contented with the unfolding course of their lives, what was the need for the musings of an old hunchback?

Next page