The In-Between Church

The In-Between Church

Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations

Alice Mann

An Alban Institute Publication

Scripture quotations in this volume are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Copyright 1998 by the Alban Institute, Inc. All rights reserved.

This material may not be photocopied or reproduced in any way without written permission. Go to http://www.alban.org/permissions.asp.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-73670 ISBN 978-1-56699-207-7

Contents

Readers may be puzzled at the phenomenon of a Scottish bishop writing a foreword to a book by an American Episcopal priest on how to navigate the complexities of size transitions, so I offer a word of explanation and introduction.

The 1988 Lambeth Conference called upon the provinces of the Anglican Communion to inaugurate a decade of evangelism and there-by precipitated a crisis for many of the bishops. My own dilemma was probably characteristic. I describe myself as a liberal Catholic, one of the many subspecies within Anglican zoology. Historically, we have rarely been explicitly evangelistic in our missionary approach, tending instead to the magnetic model of church growth: doing our liturgy and our Christian living in a way that exerts a powerful gravitational pull on people, who are drawn by the beauty of what they see.

After Lambeth 88 it was quite obvious to me that our communion could no longer rely solely on the magnetic model of evangelism if it was to survive, let alone flourish. But most of the models of active evangelism came from within the evangelical tradition, and the methods they espoused were usually based on an understanding of the Christian message with which I was not theologically comfortable. When I tried to adapt methods evolved by evangelical Christians to the more Catholic ethos of the Scottish Episcopal Church, I encountered little success and not a little opposition. And thats when I met Alice Mann.

I was invited by the Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas to act as chaplain at one of its conferences on parish evangelism. Mann was the consultant at the conference, and she combined a passion for church growth and a skill in the methodologies that can deliver it with a theological approach and personal style that was sympathetic to our ethos. We soon appointed her as a consultant to the Scottish Episcopal Church. As a result of Manns work with us, we have come to recognize the vexing phenomenon of the size plateau, in which a congregation is stuck in a behavioral syndrome that makes its life and work hard to develop. Mann likened this experience to living with a turbulent adolescent, and she knows we need strategy as well as insight if we are to use the experience creatively. The fundamental insight required is an honest acknowledgment of what is happening.

Manns gift for using every crisis as an opportunity for the practice of faith is well expressed in this little book. It is rich with organizational insight, but its theological approach is what will make it a particularly useful primer for congregations enduring the turbulence of size transitions. One of its truly incarnational insights is the importance of applying organizational theory to the life of the Church: we must understand the human nature of structures that express the Spirit. The book convincingly demonstrates that understanding institutional life can help us discern the unconscious forces that often drive the life of the church. Mann calls us to a process of self-examination that can be entertaining as well as illuminating.

In Scotland, give or take a cultural nuance or two, well soon be working with this book, so it gives me great pleasure to commend it to readers everywhere.

The Most Reverend Richard F. Holloway Bishop of Edinburgh, Primus

Scottish Episcopal Church

When I was ordained 24 years ago, I had barely thought about the meaning of a congregations size. To me, a big church mostly meant a cathedral-type building. Tiny, family-size congregations were also outside my comprehension. I had grown up somewhere in the middle.

My childhood parish, once a country church, found itself surrounded by the suburban explosion of the 1950s. I was in the first class of children to attend the brand-new school (still under construction for my whole elementary education) instead of the two-room building behind the church. I remember what big news it was when, for the first time, a young priest was assigned to assist Father Daly. By the time I left college, that church had far outgrown its century-old stone building, even with multiple service times, and had spawned a brand-new congregation on the other side of town. Somehow, with little theory and no consultants, that church figured out how to change size in response to its environment.

While some congregations today may still make sound, intuitive judgments about scaling up (or scaling down) in response to their environment, most church leaders find these issues daunting. I hope that the following chapters will clear away some of the fog around questions of changing size, and help you discern the leading of God for your congregation.

While the book should be useful to the individual reader, it is meant to be the sort of volume that pastors and lay leaders can pass around to each other or read in the context of a study group. Each chapter ends with a section entitled Biblical Reflection and one called Application Exercise. I hope you will not skip over the passages and questions provided. They are integral to the process of discernment.

What Is a Size Transition?

Weighing the Giant Fly

One of my math teachers in high school was also the football coach. Mr. Clark liked to liven up the classes with some sort of action, so he showed us part of a horror movie and asked us to estimate the weight of the villain, a giant fly about 12 feet tall. To create this towering insect, the filmmakers had photographed a real housefly and showed the enlarged image standing next to human beings apparently half its height.

Look at those legs, Mr. Clark said. Could those legs hold up a twelve-foot fly?

Well, why not? we asked.

The whole figure had been enlarged in exact proportion to the original. If the legs of the little fly were sufficient to support the body, why would it be any different for the big fly?

Suppose a real housefly is a centimeter long, a centimeter tall, and a centimeter wide. Suppose he weighs one gram. Wouldnt a fly twice as big weigh two grams? In fact, if you double all the dimensions of the fly, you will quadruple the shadow he casts on the picnic table at noon and increase eightfold the amount he weighs. Our giant fly would need thick legs like an elephant in order to stand up, and he wouldnt be much of an aviator.

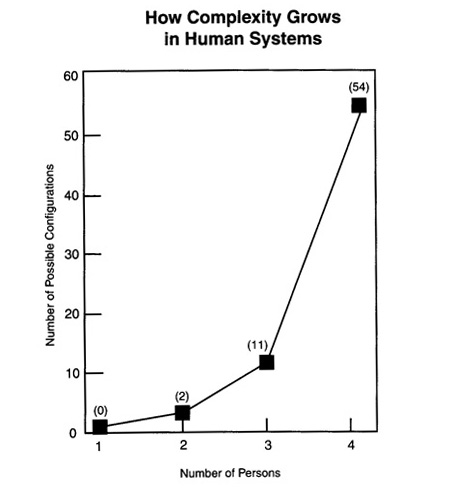

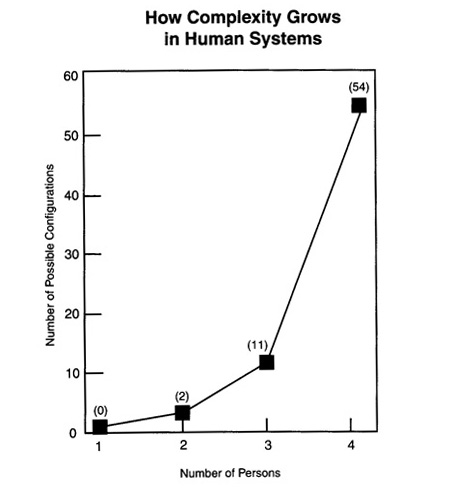

When organisms change significantly in size, they must also change inform. Thats just the way the world works, and the rule holds true for social as well as biological organisms. Kenneth Blanchard has shown how the number of possible interactions multiplies as a social system grows in tiny increments. With three people in a room, 11 different configurations of communication are possible: A speaks to B; A speaks to B in the presence of C; and so on. Add a fourth person and the number spikes to 54.

For the last three decades or so, students of religious systems have tried to describe the changes inform that must occur in order to allow a congregation to change in size.