When I was a little boy my father once lifted me upon his shoulders that I might see the President of the United States as he passed us. That was not the first time I had stood upon the shoulders of another, nor was it the last.

I would be shamefully dishonest and disgracefully uncharitable if I were not to acknowledge those who, like my parents, have challenged me to be dissatisfied with my present accomplishments, and have stimulated me to new ones.

Much thanks must go to my wife, Nancy, and my four children, Jimmie, Joey, Judy, and Johnnie, who were patient when time was stolen from then. Their love and devotion are irreplaceable.

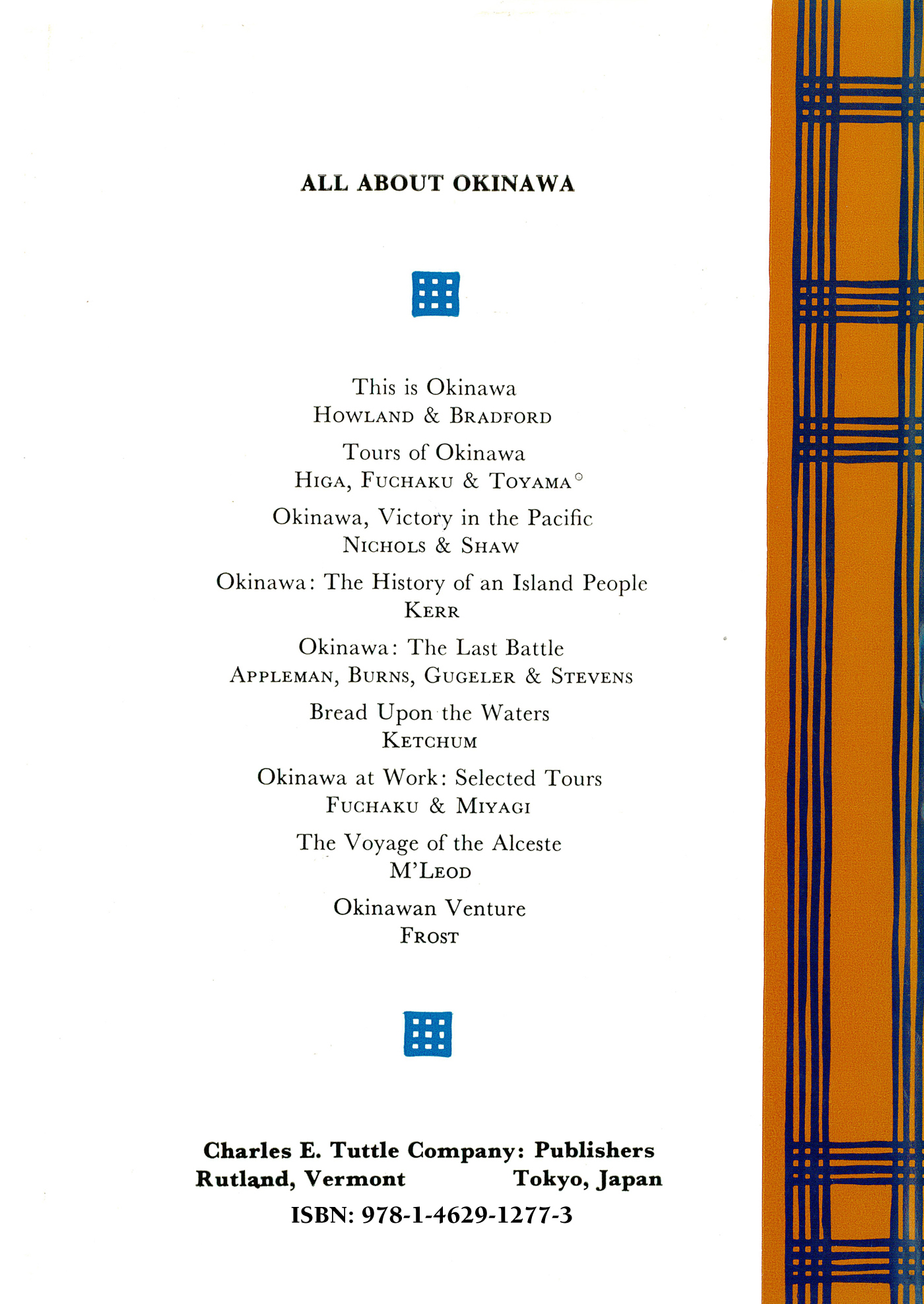

Publications by Dr. William Lebra, Okinawan Religion; and Dr. George H. Kerr, Okinawa: The History of an Island People; and Dr. Clarence J. Glacken, The Great Loochoo, were especially helpful. Professor Sokyo Ono's Shinto: The Kami Way, was both stimulating and informative. Thanks are also due the University of Hawaii Press for permission to quote from Okinawa Religion by William P. Lebra and from Ryukyuan Culture and Society: A Survey.

Special appreciation must go to Dr. William Stockton, Anthropologist, and Mr. Sam Kitamura, Public Relations Department, USCAR, for encouragement and constructive criticism. Any errors or false conclusions, however, must rest upon me.

Typing and editing was done by Mr. William Stem, Jr., who labored long and hard over penmanship that has always served as a bewilderment both to my teachers and to my friends.

James C. Robinson

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bull, Earl R., Okinawa or Ryukyu: The Floating Dragon. Newark (Ohio), 1950.

Bunce, William K., Religions In Japan . Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1960.

Burd, William W., Karimata: A Village in the Southern Ryukyus. Pacific Science Book, National Research Council, Washington, 1952.

Fuchaku, Isamu, Gasei Higa & Zenkichi Toyama, Tours of Okinawa . Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1963.

Glacken, Clarence J., The Great Loochoo . Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1960.

Haring, Douglas, "Chinese & Japanese Influences," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey . University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Kaneko, Erika, "The Death Ritual," Ryukyuan Culture and Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Kerr, George H., Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1958.

Kokubun, Naoichi & Kaneko, Erika, "Aspects of Prehistory," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Lebra, William P., "The Okinawan Shaman," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Lebra, William P., Okinawan Religion. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Mabuchi, Toichi, "Spiritual Predominance of the Sister," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Meighan, Clement W., "Early Prehistory," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Narita, Yoshimitsu, "Dialect Areas," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Ono, Sokyo, Shinto: The Kami Way. Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1962.

Takamiya, Hiroe, "Late Prehistory," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

Uemura, Yukio, "Ryukyuan & Japanese Dialects," Ryukyuan Culture & Society: A Survey. University of Hawaii Press, 1961.

The Cultural Assets Protection Commission of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands. Cultural Assets of the Ryukyus, Naha.

Anonymous. "Ryukyus Hold On 70 Ancient Superstitions," Life On Okinawa, October 1965.

Okinawa Christian Mission Directory, 1965.

Missions Directory Ryukyu Islands, 1965.

Chapter 1

SOME

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS

OF OKINAWA RELIGION

KAMI

From time immemorial the people of Okinawa seem to have believed in kami; it is a basic expression of their ancient folk religion. Kami is an animistic concept that all things living and dead possess a spirit; they may dwell, therefore, in all things animate or inanimate. As superhuman forces they possess the power to either help or hinder human endeaver. There are many kami, each independent from the other; it is necessary, therefore, to be in bad grace with only one kami to experience unfortunate consequences. Kami are deities, but the line between man and kami is as vague as the concept of kami itself. Nevertheless, since kami are seen as the source of divine intervention in human life, they function as gods for the believer.

Kami act in various ways: they supervise, influence, alter, or inform. They may also be organized in categories and arranged according to rank. According to one writer the heaven or natural phenomena kami is the highest. This is the kami who is said to have ordered two sibling-kami to create Kudaka Shima and populate the island. This kami is not to be confused with the Judeo/Christian God of Creation. Next in rank are the place or location kami. These are the kami of the well, pigpen, hearth, or paddy. Third in rank are the occupational or status kami. It is believed that every person has a kami that determines his spiritual status. Kami-persons (kaminchu) are thought to possess the highest spiritual status because of the kami that has possessed them. Status kami (saa) can be neither acquired nor rejected. One's status, it is believed, may be determined by a yuta or a fortuneteller; but since most religious offices are inherited, this tends to be determined by birth.

Ranking fourth, but by no means unimportant, are the ancestral kami (futuki). The last category is that of the kami person (kaminchu) who, despite human responsibilities (by some as a wife and mother), assumes a semi-devine status when she dons the white kimono and functions as a priestess. Both priestesses and yuta are commonly considered to be kami persons, although there is some question concerning the latter.

Since kami may be present in all things, their number is almost without end. Among the most influential kami in every day life are the hearth/fire kami (fii nu kang/kami); ancestral kami (futuki); life sustaining kami (mabui); remote ancestor kami (chiji), whom one serves and who offer guidance; ghosts (majimung); and a male spirit who lives in the Indian banyan reet (kijimunaa). In addition to these there is thought to be a nonpoisonous snake called "akamataa," who is said to possess the power to transform himself into a handsome young man with the power to seduce women. Those who fall prey to his charms are said to give birth to snakes. At least one shrine has been built in celebration of his defeat, the Kannondo Buddhist temple, at Yabu Village; this temple was originally built about 400 years ago.

AUTHORITY FOR KAMI FAITH

In traditional Okinawan thought there are two sources of knowledge: empirical, which is available to everyone; and supernatural revelation, which is limited to kami-persons. Kami-persons are instructed through hearing or dreaming, while being bodily possessed (completely or partially), or during a waking vision at which time the kaminchu is in full possession of her senses. In the latter experience the individual is a spectator or participant in something which he both hears and sees. Since this instruction is revelatory in nature, formal training is rejected as being not necessary; actually, training for the religious office is acquired through association with other priestess and yuta are considered to be divinely conferred. This is balanced in the thinking of the ordinary person by consultation with several kaminchu and the acceptance of the most reasonable opinion.