Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

EDITORS INTRODUCTION

1925. Broch, or the Pedagogue

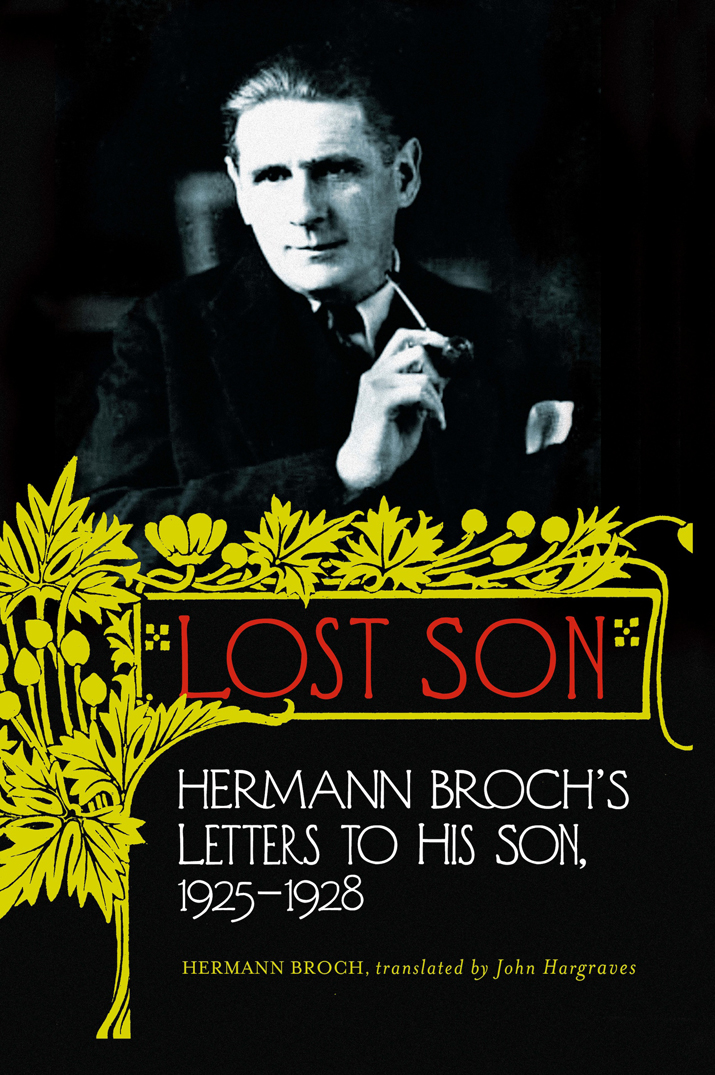

HERMANN BROCH (18861951) was one of the greatest writers of German in the twentieth century, ranking with Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka, Hermann Hesse, and Robert Musil. Like Musil, with whom he is often compared, Broch became a writer after first pursuing a technical and commercial career. The works for which he is best remembered are The Sleepwalkers and The Death of Virgil, the publication of which prompted his being twice nominated for the Nobel Prize.

Broch felt that his true calling was teaching. He never cared for the career his father had more or less forced upon him, working in the familys textile business, and as an alternative he set his sights on becoming a university-level professor. His 1933 novel, The Unknown Quantity, has elements of autobiographyto the extent, at least, that the protagonist is an assistant professor of mathematicsand elements also of that frontier where epistemology and mathematics meet. In 1925, when Broch was nearly forty, he matriculated as a student of mathematics and humanities at the University of Vienna and was at the time planning the sale of his familys textile-weaving factory in Teesdorf near Vienna. He planned to get a doctorate in the faculty of philosophy, but he became so disillusioned by the day-to-day-business of academe that he soon gave up his wish to become a professor. His interest in literature was just as strong as his scientific bent, and he hoped that a wider field of influence would be available to him as an independent writer. When one examines Brochs philosophical poetics, as expounded in numerous essays and letters from the early 1930s, one is struck by the ethical intentions inherent in his literary efforts. He wants to uncover new realities, and to lend new insights to the understanding of his age, to point out future trends. This basic ethical impulse can be noted in Brochs novels, The Sleepwalkers, The Spell, The Death of Virgil, and The Guiltless. Even his eventual abandonment of literature, more or less after the 1945 publication of The Death of Virgil, had a pedagogical motivation. During the time of National Socialismbefore and during his exile in the United Stateshe wanted to educate the public through political studies of democracy, through juridical deliberations on human rights, and through psychological analyses of mass hysteria, to help make a contribution to pest control, as he called it.

The offspring of pedagogues do not have an easy time of it, and Armand, the only child from the marriage of Hermann Broch and his wife, Franziska, eventually got to know this better than most. Most families are divided by generational conflict at some point or other, but the gap here dividing the fathers and the sons views of life seemed unbridgeable. Hermann Broch belonged to the Expressionist generation, for whom the First World War had brought a historical break that marked them for life. Their reaction to this historic catastrophe was characterized by a heightened interest in philosophy and literature, in criticism and utopian ideas. Armand, on the other hand, came of age in the era of the so-called New Objectivity (neue Sachlichkeit), during the raucous, hedonistic decade of the Roaring Twenties.

Armand was fourteen when in the fall of 1924 his father sent him to one of the most expensive, elite, and exclusive boarding schools of Europe, the Collge de Normandie in Clres near Rouen. Hermann Brochs schooling had been nothing like this: He had attended the Technical College for Textile Manufacture in Vienna (19046) and the Spinning and Weaving College in Mlhausen (19067). Brochs parents were both Jews, but the family was not observant, and Broch eventually converted formally to Catholicism when he married his aristocratic fiance Franziska von Rothermann. Although Broch was broadly familiar with Jewish culture, he did not feel particularly Jewish himself and raised his son apart from this tradition. The attempt to give his son advantages that he had been denied could perhaps be seen as another facet of Brochs assimilationist upward social mobility.

At the Collge de Normandie, however, Armand was surrounded by students from millionaires families or the aristocracy, most far wealthier than the merely well-off Brochs. The tone was set by students interested in sport of all kinds: especially fencing, tennis, golf, and riding, or who were crazy about the professional race car drivers in the latest model Mercedes, Fiats, or Renaults, and on school open days, the Collge horse show was a major event. There was no instruction per se in hunting, but there was a school club dedicated to teaching the art of playing the bugle or hunting horn. Dignitaries like the American ambassador were invited to such events, as were celebrities like the air travel pioneers Clarence Chamberlin and Charles Levine, the first pair to fly across the Atlantic, two weeks after Charles Lindberghs solo flight. The students were jazz fans, played saxophone and banjo, danced the Charleston, saw the latest films from Hollywood and Europe in the school movie theater, took extravagant trips, and paid visits to one another at their parents castles and villas, and apart from that made sure they acquired the necessary knowledge to pass the baccalauratthe bachot, as it is informally calledand thus attend and graduate from one of the grandes coles in France or elite universities in England or America before following in their fathers footsteps to run the family business, inherit the familys ancestral estate, or take a leading role in business, politics, or a government ministry. That was the general rule, and at first Armand seemed no exception. He, too, spent most of his time playing tennis, dancing the Charleston, reading car magazines, and making sketches of the latest model automobiles, taking trips and weekend excursions to fellow students villas or French spas, which had by now become the established watering places of high society.

One friend of Armands who is often mentioned in the letters was a classmate, Ernest Labouchre, whose father was an exceedingly rich Dutch banker, and whose grandfather, the chief executive of Standard Oil in France, was married to an heiress and lived in a castle. Armand visited the family on occasional school breaks. The Labouchres lifestyle in Paris, in the French countryside, and in Amsterdam was to Armand like a dream come true, and his father had a difficult time bringing his son back down to earth, and to the reality of his own background: that of a minor manufacturing family. Simple etiquette would normally require the Brochs inviting young Ernest on a reciprocal visit to Teesdorf, their provincial hometown outside Vienna, and stay in their less-than-baronial superintendents residence located directly on the weaving mill grounds. His fellow students knew intuitively that Armand did not quite belong to their social class. And so the son writes to the father at the very start of their correspondence that he feared the bullies in his class might make him their favorite victim. Nonetheless he was able to gain their respect and a certain popularity through better-than-average performances at tennis and golf. Of course his father did not recognize accomplishments of that sort: He only wanted to see superlative grades in his sons academic subjects, and with this son they were just not forthcoming. The only thing the father ever reluctantly praised was Armands skill at sketchingbut not, alas, the boys drawings of his favorite subject, automobiles. At one point he arranged a little job for Armand: to design a new letterhead for the canvas factory of his friend Felix Wolf, which was accepted and for which the son received a small fee.