Paul Spencer

Youth and Experiences

of Ageing among Maa

Mod els of Society Evoked by the Maasai, Samburu,

and Chamus of Kenya

Managing Editor: Kathryn Lichti-Harriman

Language Editor: Steve Moog

Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/.

Copyright 2014 Paul Spencer

ISBN: 978-3-11-037232-8

e-ISBN: 978-3-11-037233-5

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

Managing Editor: Kathryn Lichti-Harriman

Language Editor: Steve Moog

www.degruyteropen.com

Cover illustration: Paul Spencer

Contents

Outline of Chapters

Introduction

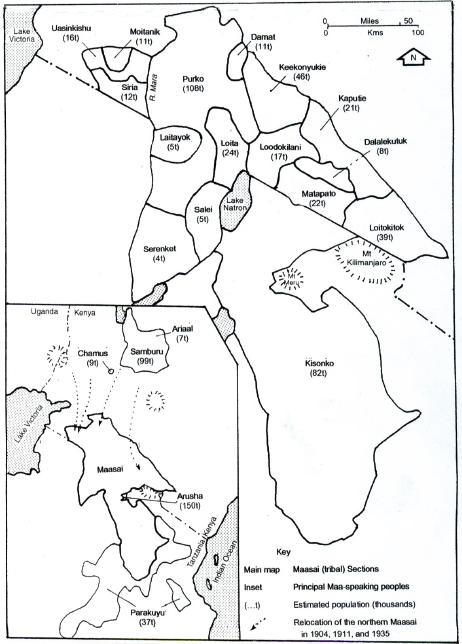

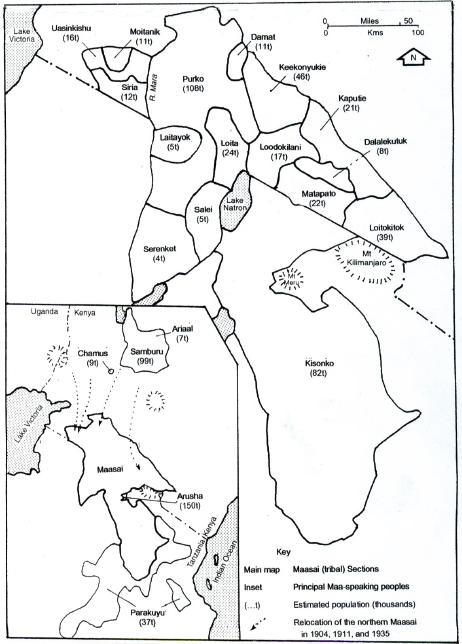

The Maa peoples of East Africa share the same language and are predominately nomadic pastoralists. The Maasai have a dominant position at the centre of this area, with 60% of the Maa population dispersed among 16 independent tribal sections. This volume stems primarily from anthropological fieldwork among the Maasai of Matapato and among the Maa-speaking Samburu, who live in the northern reaches where conditions are harsher. It is convenient although a matter of speculation to regard the Samburu as close to some proto-Maasai ancestral group before the Maasai expanded southwards against other Maaspeakers, spurred by their legendary Prophet Supeet during the first half of the nineteenth century. Conditions were more arid in the north, families were more nomadic and warfare seems to have consisted of lightly armed skirmishes and mobile tactics. The easier conditions of the south permitted the Maasai to mount more heavily armed and organized companies and the development of more stable territories defended by strategic warrior villages (manyat, s. manyata). A third Maa-speaking group are the Chamus, who have had close links with the Samburu, borrowed the idea of manyat from the Maasai at one point, and provide an independent insight into the history of the area.

A significant feature of inland pastoralist societies in East Africa is the variety of age-based organizations that group men into cohorts according to age from initiation in youth until the cohort or age-set dies out. Historically, this type of society has been described in every continent, displaying a similar range of ramifications. This suggests some basic principles of age-based existence, parallel to those of kinship elsewhere, but raising questions in some quarters of whether this type of society could possibly have worked. East Africa provides the principal surviving cluster of age-based societies, among whom the Maasai are the best known.

A likely cause of the demise of age systems generally is the emphasis on equality within each age-set that cuts across family interests, whereas the spread of world trade and hence capitalism has created inequalities that tend to be perpetuated within families. The strong commercial streak in Islamic societies in East Africa, for instance, has led to cumulative inequalities that are inherited down the generations. Differences of wealth between families also occur among age-based pastoralists, compromising their ideals of equality within each age-set. However, these tend to be temporary rather than cumulative: their herds can multiply quite rapidly over a period of years and then be wiped out through drought, epidemic or raiding, giving the impression of a sawtooth profile of growth and collapse. In these conditions, the ideal of age-set equality applies to long-term prospects and opportunities rather than current wealth. In the short term there is an emphasis on sharing products of the family herd rather than sharing the living herds which are treated as a reserve capital. With no trade routes through the area, Islamic and other traders were unable to penetrate the Maasai in their traditional setting, and the Maasai were unable to build up capital in the long-term. In contemporary society, the Maa are an anachronism, but they can provide useful insights into aspects of ageing from childhood onwards that have a more general relevance.

Map: The Maasai and Maa-speaking Peoples in 1977

The present work arose indirectly from an invitation by Oxford University Press to submit an annotated bibliography on The Maasai and Maa-speaking Peoples of East Africa for their Oxford Bibliographies Online programme in African Studies. The strict format that they proposed appealed to me and the labour involved stretched my understanding of the Maa-speaking region. This led to the notion of resurrecting some earlier dispersed articles and bringing them together as a collection that complemented my published ethnographies. These articles reflect opportunities to pursue particular models of Maa society, responding to conference themes and seminar series. They lay bare some fundamental aspects of structure that tend to be obscured in comprehensive ethnographic accounts.

Two approaches to models of age systems are possible. The first is to strip them of their social context and discern some basic rules that govern the process of ageing and the succession of generations. This provides a series of ideal types constructs that pose and resolve some basic problems of how they work. It is this approach that Frank has adopted in his outstanding analysis of recorded age systems throughout the world, stripping them down to the bare bones of rules and principles, simplifying them in order to arrive at a basic understanding of complexity. Maa age systems are at the simplest end of Stewarts spectrum with no generational complications (Maasai) or just one unproblematic restriction (Samburu). In this sense, the Maasai provide an ideal type at the level of rules and procedures.

An alternative approach towards models is adopted here with reference to selected topics that arose from the study of Maa society and especially their age systems. These models were the product of perspectives offered by my Maa informants on the one hand and insights borrowed from a variety of disciplines and parallel fields on the other. Each chapter in this volume views the Maa through a different lens that throws light on their system in order to clarify some aspect of a more complex whole. As Max Weber pointed out, models are abstractions that simplify and distort reality, but they also throw further light on it, and ultimately we can only perceive reality through models. There are cross-threads and a logical sequence between the chapters, but there is no overarching model other than an attempt to expand an understanding of Maa society by viewing it from a variety of angles and comparing the Maasai, Samburu and Chamus as a means towards this diffuse end.