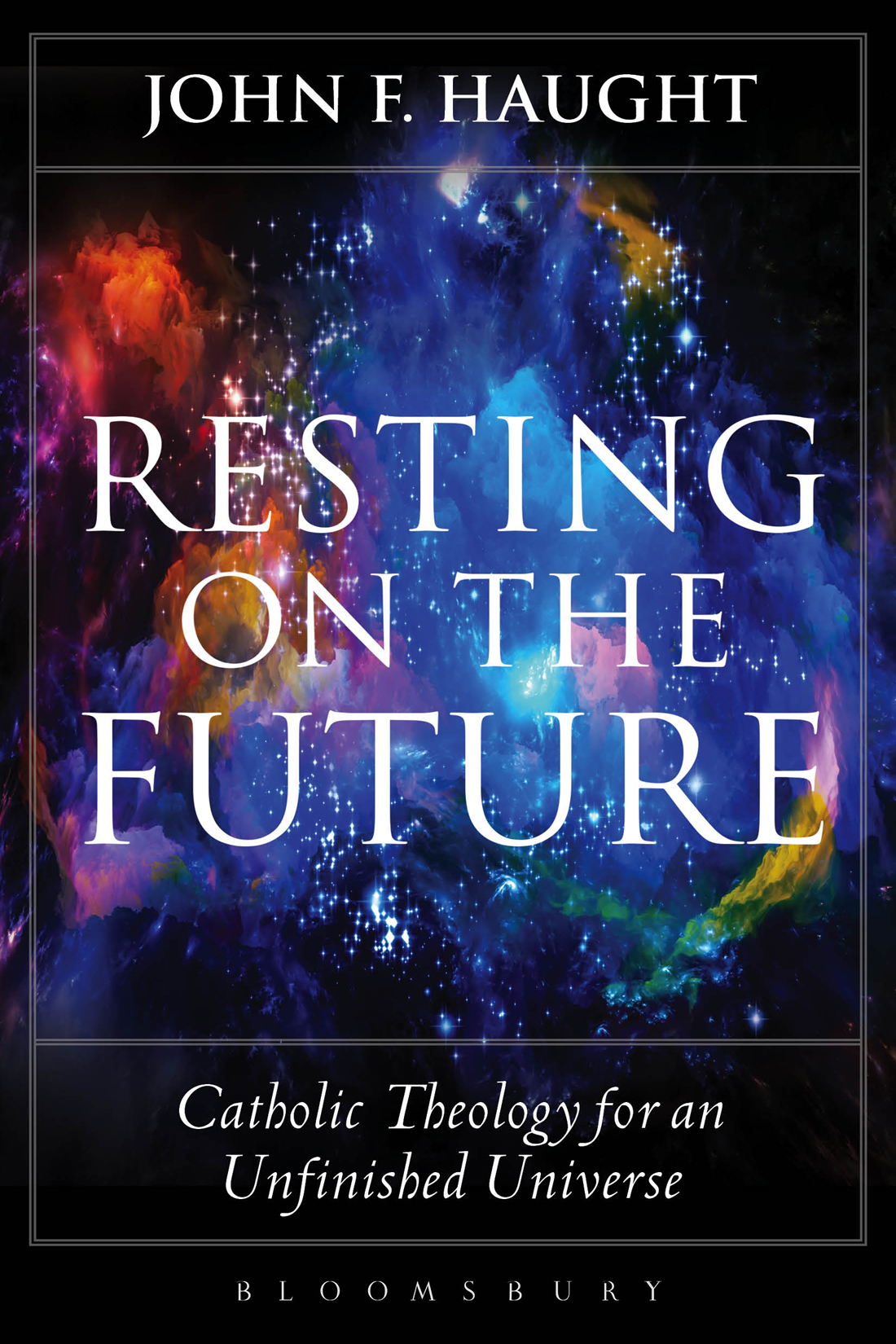

Resting on the Future

To Evelyn

Resting on the Future

Catholic Theology for an Unfinished Universe

John F. Haught

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc

Contents

The theological vision expressed here has been developing for many years, and it is far from finished. I offer it now only with the expectation that it will require further scrutiny and revision in the future, a process that I welcome. The present book considers in a fresh way, this time in the context of Roman Catholic theological inquiry, issues in science and theology that I have been working on for many years. Several chapters adapt and modify ideas presented in more rudimentary form earlier, and so I wish to acknowledge the following: Chapters 1 and 2 borrow from my chapter Teilhard de Chardin: Theology for an Unfinished Universe, in Ilia Delio (ed.), From Teilhard to Omega: Co-creating an Unfinished Universe (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2014), 723. Chapter 4 uses material from my chapter To Women and Men of Science: Science, Spirituality and Vatican II, in Anthony J. Ciorra and Michael W. Higgins, (eds), V atican II: A Universal Call to Holiness (New York: Paulist Press, 2012), 15065. Chapter 5 modifies and expands on a lecture I delivered to the American Teilhard Association, Darwin, Teilhard, and the Drama of Life. And Chapter 13 draws in part on my essay Transhumanism and the Anticipatory Universe, in John Haughey and Ilia Delio (eds), Humanity on the Threshold: Religious Perspectives on Transhumanism (Washington, DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, 2014).

I want to thank Haaris Naqvi and the editorial staff at Bloomsbury Press for the cordial and careful way in which they have received and shepherded this work toward publication. And in a special way I want to express my gratitude to Ursula King and Charles OConnor, III for their helpful comments and advice.

Science has now demonstrated beyond all doubt that our universe is unfinished. It is still coming into being. Discoveries in geology, biology, cosmology, and other fields of science have shown that nature is on a journey far from over. Knowledge that the world is a work in progress, I believe, provides a fertile new framework for thinking about the meaning of Catholic faith and life. If we take seriously the fact that the universe is a drama still unfolding, we may think new thoughts about God and other perennial themes of theology, and we may do so without losing any of the traditions great treasures. Above all, hope will gain an expansive new horizon, one that can renew our spiritual lives and widen our sense of the coming kingdom of God.

News that the universe is dramatic, however, has yet to penetrate deeply into Catholic sensibilities. Our devotional life still presupposes an essentially static cosmos. The Church continues to nurture nostalgia for a lost original perfection and longs for union with an eternal present untouched by time and history. Its ageless inclination to restore an idyllic past or take flight into eternity has bridled the spirit of Abrahamic adventure and dampened the sense of a new future for the whole of creation. Meanwhile, intellectual culture at large remains stuck in a stagnant materialist pessimism that also suppresses our native need for a future in which to hope.

This book asks what Catholic faith might mean if we take fully into account the fact that our universe is still on the move. What would it imply theologically if we looked forward to the future transformation of the whole universe instead of trying to restore Eden, or yearning for a Platonic realm of perfection hovering eternally above the flow of time? What if Catholic theologians and teachers began to take more seriously the evolutionary understanding of life and the ongoing pilgrimage of the whole natural world? What if we realized that the cosmos, the earth, and humanity, rather than having wandered away from an original plenitude, are now and always invited toward the horizon of fuller being up ahead?

The new scientific setting is one in which our universe must be pictured as still coming to birth. We live in the age of evolutionary biology and Big Bang cosmology. These fields of research, along with many others, have demonstrated that cosmic and biological origins were relatively rudimentary and that enormous spans of time were required to bring about the wondrous outcomes we call life, consciousness, and culture. The universe has always had a future and has always had to wait. We know this better than ever now that the new sciences have lengthened our sense of cosmic time beyond all previous imagining. Until recently, we had no idea of the almost fourteen billion years during which the universe has labored to reach its present state of being. Creation, we must now acknowledge, has not been instantaneous, and it has a future stretching toward we know not where.

This new sense of a cosmic journey, I believe, is much more momentous spiritually than most Catholics seem to have noticed. Since Christianity is a forward-looking faith and feeds off the future, Catholics cannot be content with seductive dreams of an initially perfect creation or with contemplation of an eternal now. In our age, it is more appropriate instead to picture the fulfillment and healing we look for, in a more biblical way, as a state that has never yet been fully actualized but that we hope will come into being in the future by Gods grace and creaturely cooperation. The Bibles sense of time and history arouses hope for an unprecedented future even as it deflects nostalgia for a paradisal past or a state of perfection cut off from the world of becoming. The ancient narratives of a promising God, one who always opens up a new future whenever dead ends appear, encourage us now to move beyond preoccupation with a lost Eden and an eternal present. Abrahamic faith directs us outward and forward into an open future. It instructs us to look for fulfillment up ahead, in the direction of new creation and a fulfillment of the cosmic process yet to appear. It encourages us to wait for the advent of a God who draws the world toward new being from out of the future.

Evolution and the cosmic process, I argue in these pages, sit comfortably in a religious setting grounded in wayfaring hope. Instead of diminishing our sense of divine transcendence, science now allows us to experience and cherish the all-surpassing love and power of God in a vitalizing new way. A science-conscious theology, therefore, can remain entirely continuous with the long history of our religious searching even as it widens the quest for fulfillment. Evolution and cosmology do not require the termination but the transformation of our search for meaning and redemption.

Without intending to do so, scientists over the last two centuries have raised the curtain to a new future for the universe and, along with it, spiritual space for a fresh throb of hope. Theologians may still draw upon Catholic traditions affirmation of divine transcendence, incarnation, and sacramental presence. However, science now gives these classic themes an unprecedented dramatic twist that tilts all of creationand spiritual seekingin the direction of a new future. Sciences fresh picture of nature-as-narrative invites theology to transplant the central biblical motif of divine promise onto a cosmological terrain that can give new breadth, nourishment, and vitality to our spiritual and ethical lives. It makes room for a theology that frames our unfinished universe with Abrahamic hope. So, when I refer in these pages to an unfinished universe, I am pointing to a world that may have future outcomes unimaginable at the present. In any case, if there were ever an occasion for the renewal of hope, it lies in our new sense of a still-emerging cosmos.