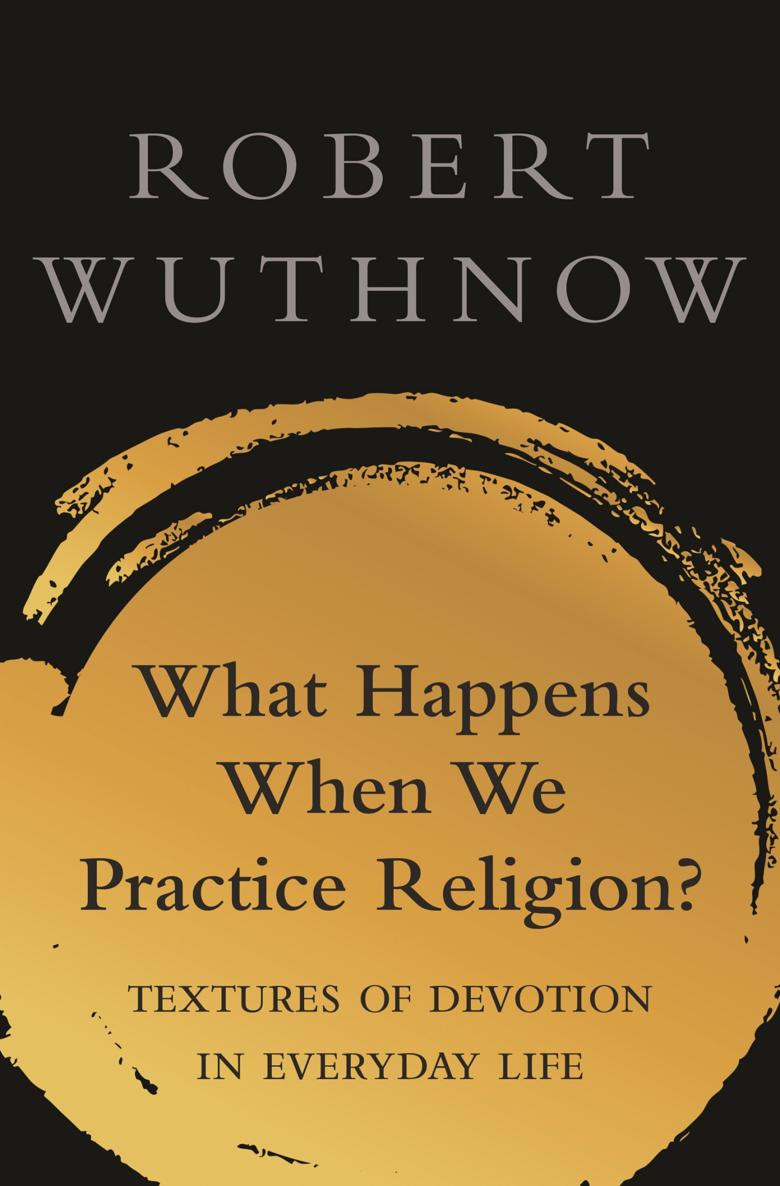

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WE PRACTICE RELIGION?

What Happens When We Practice Religion?

TEXTURES OF DEVOTION IN ORDINARY LIFE

ROBERT WUTHNOW

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wuthnow, Robert, author.

Title: What happens when we practice religion? : textures of devotion in everyday life / Robert Wuthnow.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019024278 (print) | LCCN 2019024279 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691198583 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691198590 (paperback)

eISBN 9780691201276 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Religious life. | Spirituality.

Classification: LCC BL624 .W88 2020 (print) | LCC BL624 (ebook) | DDC 204/.4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024278

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024279

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and Jenny Tan

Production Editorial: Debbie Tegarden

Jacket/Cover Design: C. Alvarez-Gaffin

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Nathalie Levine and Kathryn Stevens

Copyeditor: Karen Verde

Jacket/Cover Credit: the cover art is from iStock

PREFACE

IN THE MID-1980S, I had the privilege of being asked to co-direct an interdisciplinary seminar tasked with bringing together faculty and graduate students interested in the intersections of religion and culturescholars from anthropology, history, religious studies, sociology, and several related programs. The seminar evolved into a center that eventually became the Princeton University Center for the Study of Religion, and under the centers auspices the seminar continued to meet weekly, engaging scholars in sustained cross-departmental conversations and serving as an extraordinary space for critical discussions of research papers, dissertations, and books in progress. The present volume is an outgrowth of those conversations and is an attempt to address one of the recurring questions that inhabited those discussions.

That question can be simply stated even though it cannot be simply answered: What do we mean when we say that people practice religion? What do we look at? What do we need to think about, not to discern some essential universal feature of religion or to advance yet another grand theory, and certainly not to revisit thoroughly trod ground about how religion functions or what it causes people to do, but to piece together the intricate textures of how it is present in ordinary life? What takes place in the immediate moment that illuminates, not the consequences of religion or what people hope to get out of it, but what they do? In brief, what happens? And what do we scholars do as we seek to understand the diverse manifestations of religious practice? What provisional concepts do we have at our disposal? What insights are there in the existing literature? What promises to be of continuing benefit? From week to week and from year to year, these were the topics that kept appearing in the background of the seminars discussions.

The discussions turned, without anyone quite being able to say precisely when or why, in two decisive directions. The first was a shift from descriptive generalizations about American religion toward approaches offering greater capacity to take account of the vast variety of religious expression in wider contexts as well as the remarkable diversity within American religion itself. To converse constructively about monastic Buddhism in China and hospice care in Japan and Pentecostal worship in a Brazilian favela, or even about yoga practice and choir practice and prayer in the United States, the point of research has to shift. Important as it is for scholarship about religion to examine the intricate details of these vastly diverse practices and to depict them in their distinctive social and historical contexts, it must also be reflexive about its aims. It has to quit searching for the underlying empirical commonalities and start looking for the heuristic devices that equip the investigations to better understand the richness of the topics at hand. It has to plunge more deeply into the webs of significance in which we are suspended, as Clifford Geertz described them, not by seeking only to discern the meanings present but also by examining how the webs are constructed. The second was a shift toward an epistemological framework that foregrounded the inevitably messy habit-driven but also improvisational character of action in the unfolding events of day-to-day life while including sufficient attention to the inequities of power that inevitably constrain those activities. Attentiveness to these situated agentic processes further underscores the importance of bringing multiple analytic tools to bear as opposed to ambitiously parsimonious explanations.

The conversations that form the back story of what I have attempted to do here operated at several levels. There was the topic of the day, which posed familiar graduate seminar questions about clarity of argument and credibility of evidence. Many of these draft presentations became journal articles and chapters in books. They contributed immensely to my own thinking, as is evidenced in the frequent references I make to them in the pages that follow. Besides the publications themselves, the seminar discussions brought to the group and to me insights from the latest developments in the various disciplines from which the participants came, thus significantly broadening the range of ideas, concepts, and considerations beyond what generally happens within single departments. Those connections were furthered in opportunities the Center provided for personal interaction with scholars in the various humanities and social science departments at Princeton and with guest speakers, panelists, conference participants, postdoctoral fellows, and visiting scholars from numerous other universities.

Any seminar worth its time leaves far more questions unanswered than it answers. The questions I was left with range far too widely to have ever been given sufficient attention. Many of them nevertheless concern the micro details of what happens when people say they practice religion, whether in mumbling a prayer they learned in childhood, embarking on an exhausting pilgrimage, arranging the items on display at a home altar, wearing a hijab, viewing an icon, or walking the dog. The questions Ive tried to address here have been with me for a long time and I do not claim to have found the best ways of thinking about them. My approach has been mostly to ask what a concept, such as practice, that appears frequently in discussions of religion is taken to mean in treatments that have little to do with religion and then to move back and forth among those discussions to see what is of greatest interest and why. As a sociologist drawn to empirical research, my approach is also to seek insights from the numerous empirical studies that have been conducted by scholars of religion in various disciplines and to interrogate those as examples of the approaches and concepts that have been of interest.