I

THE EPOCHAL INVENTION OF PRINTING

Table of Contents

The invention of printing at about the middle of the fifteenth century marks an epoch in the world's literature and in the history of the human race. Previous to this invention were spread out the events, the scenes, and the achievements of ancient and medieval times; after it came the marvelous unfoldings of the modern age.

The introduction of typography or the art of printing by means of movable types set in operation an instrumentality which, for multiplying the effectiveness of all literary productions, is far beyond all adequate conception;and this all apart from the time of its origin and the person of its originator.

Printing as an invention and an artfor it is bothhas been ascribed to the Chinese, and is said to have been known from, or from before, the dawn of the Christian Era. Mr. George H. had its real beginning in Germany, dates from the middle of the fifteenth century, and is associated with one named Johannes Gutenberg.

Gutenberg was of patrician parentage and was born at Mainz (the modern Mayence), Germany, about 1400 A. D. His life was a prolonged struggle with adverse circumstances. He died in 1468, poor, childless, and almost friendlessscarcely dreaming that he had laid the foundations of a benefaction which chronicled the turning-point of universal history, set a permanent guide-post in the world's progress, and proclaimed a new era in civilization. But so it was.

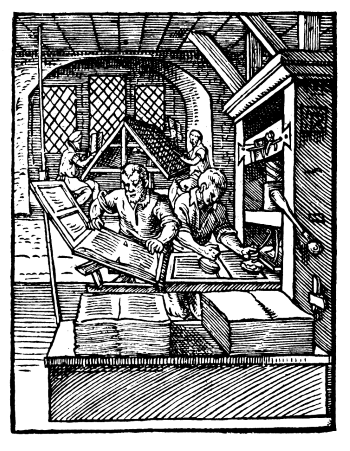

While we are without definite information as to how the first copies were printed, yet it is obvious from Gutenberg's famous forty-two line Bible that they used a mechanical press. The earliest picture of a printing-press shows an upright wooden frame with a screw post attachment by means of which the required pressure for impression was obtained and then reversed to release and remove the printed sheet. This screw post was operated by a movable bar. This kind of press continued to be used for a hundred and fifty years. The first types were cut from wood, but the ink used had a softening effect thereupon and lead was substituted. Lead, in turn, was found to be too soft a metal to resist the pressure requisite for printing. After experimentation, an alloy of antimony and lead proved to have the adaptable strength and softness; it was also capable of delicate and clear-cut manipulation. These metal types were first cast in sand and, later, in clay molds. The ink used for printing with the Gutenberg press was a mixture of linseed oil and lamp-black and was applied to the type-form by means of a "dabber" made of skin and stuffed with wool. It is stated that the first types as used in China were made of plastic clay; later, of copper; and then of lead, inasmuch as copper had come to be utilized as coin. (Putnam.)

It is worthy of our note in this connection that the first important product of the printing-press was the Bible;was devoted, as has been said, "to the service of heaven." This first "production" was on 641 leaves of vellum, two columns to a page, and forty-two lines to each column. "Probably," says Professor Dobschtz, "not more than 100 copies of the Bible were printed, a third of these on parchment. Out of thirty-one copies which have been preserved, or, to speak more accurately, are known as such, ten are luxuriously printed on parchment and illuminated, each in a different way, but all very fine and costly." printed on paper (two of which are in New York City) are all that are known to the bibliographers of the first "edition" of the printed Bible. While engaged in the production of this first book (which required four years, 14531456, to complete) Gutenberg printed smaller worksschool books and the likefor immediate financial returns. In this first edition of the printed Bible the initial letters were not struck off by press but were left, together with the marginal decorations, for after illumination by hand. A Bible printed at Mainz in 1462 is the first printed book that bears the date of its production.

II

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE PRINTING PRESS

Table of Contents

The printing-press, in many essential respects, is the most significant invention of all human history. It has touched and vitalized civilizations, countries, nations, languages, and dialects. As an invention it has contributed immeasurably to the currency and the perpetuity of all literature. It also sounded the doom of the written book. Hallam, the Historian of the Middle Ages, says: "Since the invention of printing the absolute extinction of any considerable work seems a danger too improbable for apprehension. The press pours forth in a few days a thousand volumes, which, scattered like seeds in the air over the Republic of Europe, could hardly be destroyed without the extirpation of its inhabitants." And, concerning the exposure to which the manuscript production of all previous history was subjected, he says: "In the times of antiquity manuscripts were copied with cost, labor, and delay; and if the diffusion of knowledge be measured by the multiplication of books (no unfair standard) the most golden ages of ancient learning could never bear the least comparison with the last three centuries. The destruction of a few libraries In a word, printing has the double advantage over writing of a more rapid multiplication of copies and their increased accuracy. But even with the increased accuracy of printing, few books of considerable size are issued in which errors are not to be found. It is said to be the fact that, after incredible care on the part of editors and professional proofreaders, the offered reward of a guinea for each detected error in the Oxford Revised Version of the Bible brought several errors to light. (International Stand. Bib. Encyclopedia.)

The invention of printing, through its associated process of proof corrections, has virtually exempted books from the mundane laws of decay and has greatly aided as well in their preservation and their widest circulation. This invention has made definite and immutable the records of the world since then and it has contributed also to the purification and renewal of the more ancient literary productions. Printing as an invention has given to an edition of a particular work a measure of importance hundreds or thousands of times greater in every respect save one, viz., the labor of transcription, than that which had previously attached to the production of a single book. The invention has therefore involved and necessitated a proportionately larger consideration in the making of a printed book, lest defects and errors in the type-plates from which the book is printed should become permanently fixed in a thousand or ten thousand impressions therefrom. (Isaac Taylor.) And it was printing that made uniformity of text possible. Guizot estimates the importance of this invention thus: "From 1436 to 1452, printing was invented:printing, the theme of so much declamation, and so many commonplaces, but the merit and the effect of which no commonplace nor any declamation can ever exhaust."

The invention of printing has peculiar significance within the realm of religious life and knowledge; for, in relation to the scripture text, to the spread of religious intelligence and the progress of Christianity, and to the growth and stabilization of the individual character,in a word, in relation to Redemption itself, who can apprehend, much less measure, the significance of this invention? Truly, the Bible which