Writings on an Ethical Life

Peter Singer

Acknowledgments

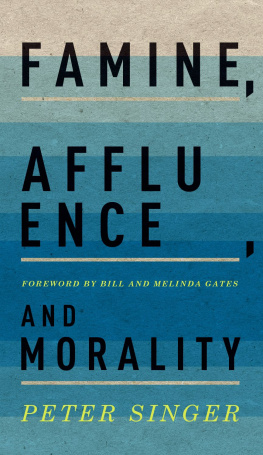

Moral Experts first appeared in Analysis, vol. 32 (1972), pp. 115117. About Ethics from Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2nd ed., 1993), pp. 114. Preface to the 1975 Edition from Animal Liberation (New York Review/Random House, New York, 1975), pp. vii-xiv. All Animals Are Equal from Animal Liberation (New York Review/Random House, New York, 2nd ed., 1990), pp. 121. Tools for Research from Animal Liberation, 2nd ed., pp. 4042, 4547, 8183, 8586, 9092, 94. Down on the Factory Farm from Animal Liberation, 2nd ed., pp. 9597, 129136. A Vegetarian Philosophy from Consuming Passions: Food in the Age of Anxiety (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1998), pp. 7275, 7780. Passages from Bridging the Gap have appeared in Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of Our Traditional Ethics (Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1994; St. Martins Press, New York, 1995) and in The Rights of Ape, BBC Wildlife, June 1993, pp. 2832. Environmental Values from The Environmental Challenge (Lanman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1991), pp. 324. Famine, Affluence, and Morality, from Philosophy and Public Affairs (Spring 1972), vol. 1, pp. 229243. The Singer Solution to World Poverty from The New York Times Magazine, September 5, 1999. Whats Wrong with Killing? from Practical Ethics, 2nd ed., pp. 83109. Taking Life: The Embryo and the Fetus from Practical Ethics, 2nd ed., pp. 138174. Prologue from Rethinking Life and Death, pp. 16. Is the Sanctity of Life Ethic Terminally Ill? from Bioethics vol. 9, no. 3, p. 4 (1995), pp. 327343 and, in part, in Rethinking Life and Death. Justifying Infanticide from Practical Ethics, 2nd ed., pp. 181191. Justifying Voluntary Euthanasia from Practical Ethics, 2nd ed., pp. 193200. Euthanasia: Emerging from Hitlers Shadow was delivered at the Third World Congress of the International Association of Bioethics, San Francisco, 1996. In Place of the Old Ethic from Rethinking Life and Death, pp. 187222. The Ultimate Choice from How Are We to Live? (Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1993; Prometheus: Amherst, NY, 1995), pp. 120. Living Ethically from How Are We to Live? pp. 154170. The Good Life from How Are We to Live? pp. 225235. Darwin for the Left from Prospect, June 1998, pp. 2630; portions of this essay also appear in A Darwinian Left (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1990; Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2000). A Meaningful Life from Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD, 1998), chapter 6. Animal Liberation: A Personal View from Between the Species, vol. 2 (Summer 1986), pp. 148154. On Being Silenced in Germany from The New York Review of Books, August 15, 1991. An Interview is excerpted from an interview aired on September 10, 1999, on WNET-TV and an interview that appeared in New Scientist, January 8, 2000.

Introduction

Had there been no protest rallies at the gates of Princeton University, had the superrich aspiring presidential candidate Steve Forbes not vowed to freeze his donations to his alma mater until it got rid of me, had my appointment as DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton not turned into what The New York Times called the biggest academic commotion since an American university tried to hire the notorious advocate of free love, Bertrand Russell, the book you now have in your hands would not have existed. For without those events the media would barely have noticed my arrival in the United States, my controversial views on a variety of ethical issues would not have become the topic of conversation around the country, and it could never have occurred to Daniel Halpern at The Ecco Press that while everyone was discussing Peter Singers views, the discussions were based largely on short quotations and secondhand summaries. Many had strong opinions about my work but few had actually read any of my books or articles. They did, however, have the excuse that my writings are scattered across a number of books and journals, not all of them easy to obtain. What people needed, Dan thought, was a handy, one-volume selection that would present my central ideas, in my own words and with sufficient context to enable them to be understood. So here it is.

What are the ideas that have caused so much controversy? They are to be found in the pages of this book, and I would prefer them to be read in their context, not in bald summary. I have spent close to thirty years working in practical ethics, which means that when I began there was no such field. The study of ethics, in philosophy departments in the English-speaking world, was then focused on the analysis of moral language and was supposed to be morally neutral; that is, it did not lead to any judgments about anythings being right or wrong, good or bad. A moral philosopher, so the standard view went, is not in any way an expert on moral issues. The short essay entitled Moral Experts that immediately follows this introduction was written to challenge this conception of the subject matter of ethics. Since its appearance in 1972, the field has changed dramatically, though not, I am fairly sure, because of any influence that essay may have had. More probably, the article was a sign of times that were already changing. The momentous issues of civil rights, racial equality, and opposition to the war in Vietnam had made the subject matter of most university ethics courses seem dry and insignificant and to spend time studying them, self-indulgent. There were more important things to do. Students were demanding relevance, and philosophers began to realize that their area of expertise did, after all, have something to say on how we can find answers to such fundamental and perennially important questions as why racial discrimination is wrong, whether we are under an obligation to obey an unjust law, and what, if anything, can make it right to go to war.

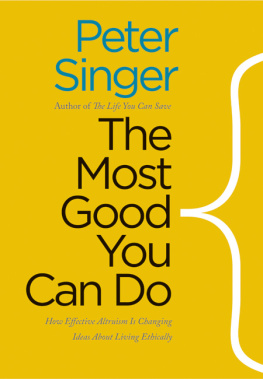

The issue on which I have made my most significant contribution to ethical thinking took a little longer to become prominent. Claims that I am the most influential living philosopher generally refer to my work on the ethics of our relations with animals. There is an element of media hype in such claims, of course, but the grain of truth in them is the fact that my book Animal Liberation played a significant role in kicking off the modern animal rights movement, and very few living philosophers have had their ideas taken up in that way. In contrast, my views on the obligation of the rich to help the worlds poorest people are potentially as significant as my thinking about animals, but they have, unfortunately, had much less influence. The issues raised by the critical work I have done on the idea of the sanctity of human life, including the discussion of euthanasia that has aroused such hostility, are in one respect less important than those two topics, simply because the treatment of animals and maldistribution of wealth affect far more people (or in the case of the animals, sentient beings), and relatively simple changes in those areas could relieve so much suffering. It is my critique of the sanctity of human life that gets the media headlines, however, because it can easily be made to sound quite shocking and there is no problem in finding people who will strenuously oppose it. Hence it provides the controversy on which the media feed.