Pushing Time Away

My Grandfather and the Tragedy of Jewish Vienna

Peter Singer

Contents

Acknowledgments

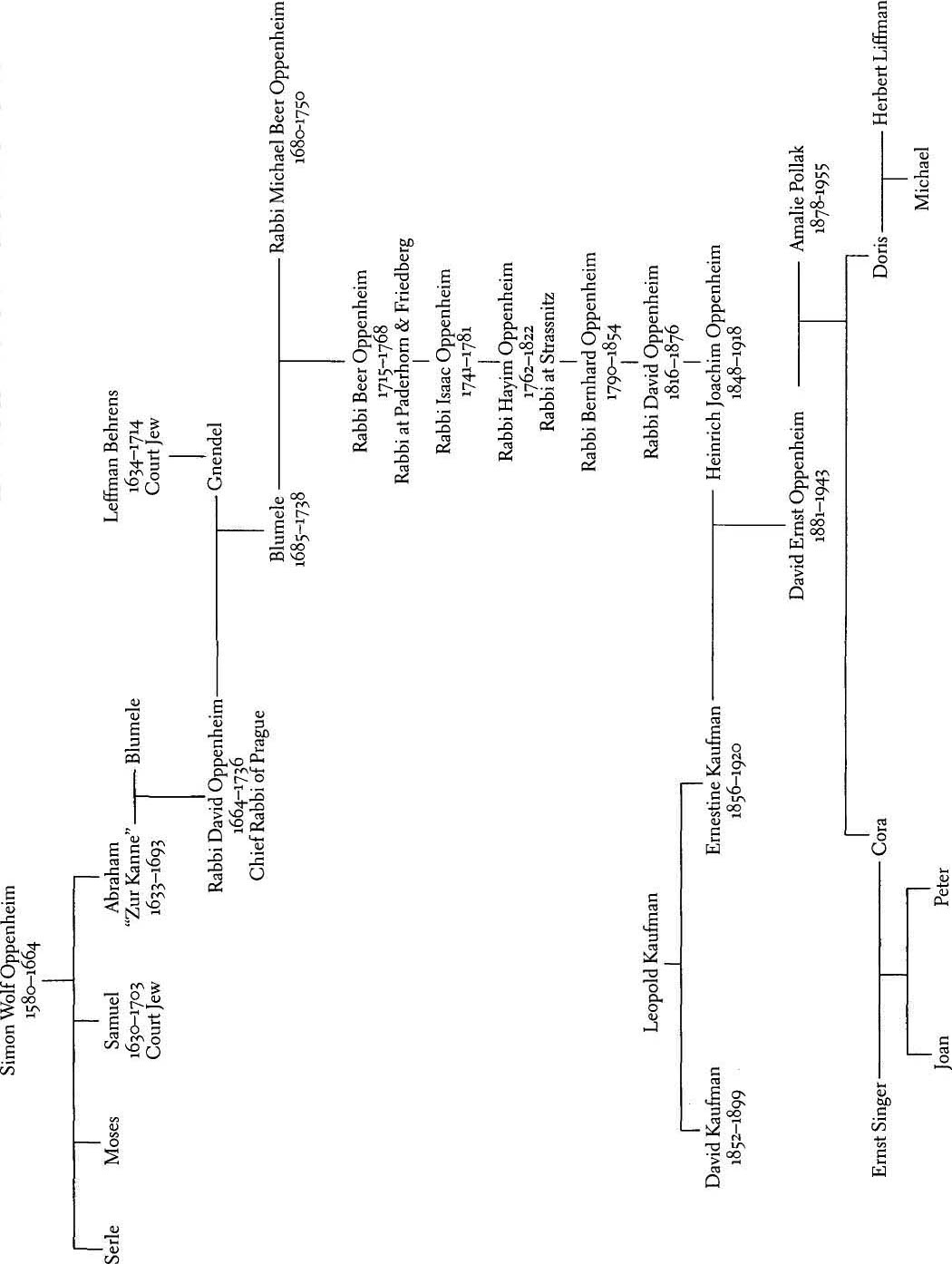

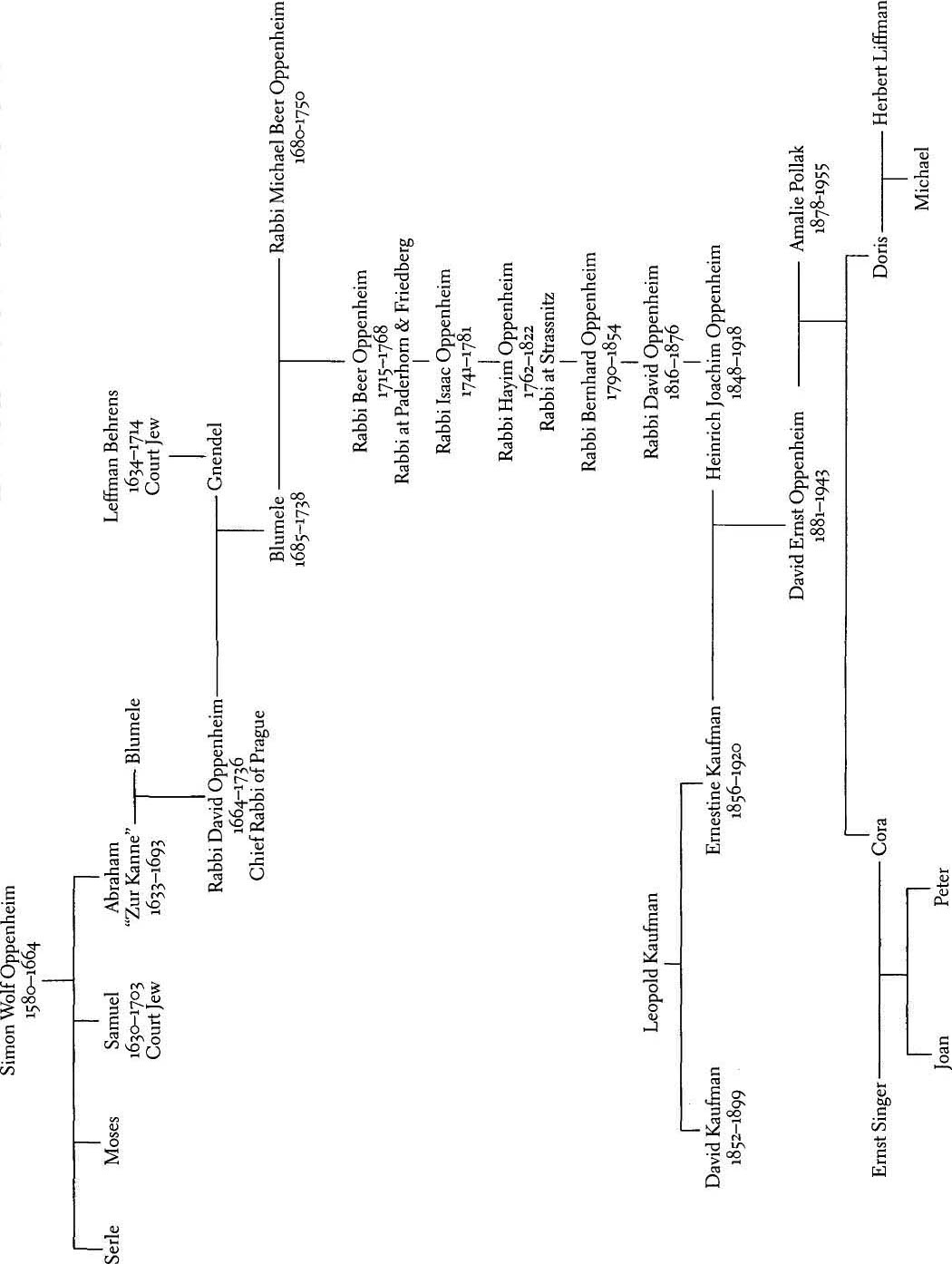

This book draws on the work of Dr. Adolf Gaisbauer, who, in collaboration with my aunt, Doris Liffman, published an edited selection of the letters that her parents (and my grandparents) wrote to their children in Australia between 1938 and 1941. Dr. Gaisbauer prefaced the letters with a biographical sketch of my grandfather, which in turn drew on Doriss Master of Arts thesis on her fathers life and times. I am most grateful to Dr. Gaisbauer for generously sharing his materials with me. I am also very thankful to Doris, as well as to Michael Liffman, her son, for allowing me free access to the wealth of materials in her possession. Other family members also contributed. My sister, Joan Dwyer, shared with me her memories of our grandmother and helped me to locate family photographs and documents. The curiosity of my daughter Esther about the contents of an old case in my mothers home led to the discovery of the letter from Amalie that is quoted extensively in Chapter 33. My grandparents nieces and nephew, Gerda Buchler, Alice Ritter, and George Kunstadt, told me all that they remembered and gave me copies of letters and photographs in their possession. Thanks to Elisabeth Mark-stein, I was able to speak to her mother, Hilde Koplenig, who remembered well meeting my grandmother on her return from Theresienstadt. Nava Kahana, the daughter of Max Rudolfer, and her daughter, Smadar Shavit, found an informative letter from my grandmother. David Stern put me in touch with his father, Kurt Stern, who not only knew my grandparents but could recall visiting the home of my great-grandparents.

Many of my grandfathers former students told me about their experiences of him as a teacher; they include Livia Karwath, Walter Friedmann, Ellen Kemeny, and Frank Klepner. In Vienna I spoke to my mothers close friend Eva Berger (formerly Hitschmann) and to the remarkable Albert Massiczek. Romana Jakubowicz generously made me welcome in my grandparents apartment, where she now lives. Thanks to Google.com and a little luck, I was able to make contact with Liz Tarlau Weingarten and Jill Tarlau, who told me what they knew of my grandmothers friend and their grandmother, Lise Tarlau.

I owe an enormous debt to Hermann Vetter and Wendelin Fischer, who between them read more than a hundred letters in my grandfathers indecipherable (to me, anyway) handwriting and e-mailed me the transcripts. Hermann Vetter was especially untiring in this work and was also extremely helpful in answering many questions I had about the content of the letters. Agata Sagans belief in the value of this project was encouraging at times when I wondered if it was worth doing, and she found information on some of the most obscure references in my grandfathers letters. Hyun Hchsmann commented on a draft and helped me to find some of the German literary sources to which my grandfather referred. Helga Kuhse and Udo Schklenk gave me valuable comments at an early stage of the project. In the Austrian court records, Marianne Schulze found for me documents about my family that I did not even know existedand thanks to Dymia Schulze for starting that search. John Oldham allowed me to see the manuscript that my grandfather wrote with Sigmund Freud. Clemens Ruthner and Reinhard Urbach provided me with information about the life of Otto Soyka and comments on my grandfathers early letters. Bernhard Handlbauer answered my queries about the records of the founding of the Society for Individual Psychology.

The support and advice of Kathy Robbins, of the Robbins Office, has been splendid. Dan Halpern and Julia Serebrinsky of Ecco have made a wonderful publisher/editor combination. Kathy and Julia bullied me into paring down a much longer typescript, a painful task that has, I grudgingly concede, resulted in a better book. Adam Goldbergers copyediting cleaned up many infelicities and inconsistent spellings.

I began work on this book while still at Monash University, in Australia, and thanks are due to Professor Marian Quartly, then dean of arts, for allowing me to take leave without pay to complete a first draft. Since coming to Princeton University, my work has benefited from the outstanding research resources available here, and from helpful comments at two Princeton University seminars. I am grateful to Josh Ober of the classics department for organizing a seminar at which some of my grandfathers letters on the classical ideas of eros were discussed and I received many helpful suggestions. Bob Kaster, of the same department, kindly assisted with the translation of a Latin quotation. For comments on a paper that raised the philosophical issue with which this book ends, about the possibility of benefiting someone after he or she is dead, I thank the faculty of the University Center for Human Values and the Centers 20012 Rockefeller Fellows. Kim Girman, my staff assistant at Princeton, was always willing to help with every task I gave her. Finally I thank Renata, my wife, for her love and companionship during the long period that it took to bring this project to fruition.

David Oppenheims Family Tree

What binds us, pushes time away.

David Oppenheim to Amalie Pollak,

March 24, 1905

PART I

Prologue

Vienna, Now and Then

January 1997

A freezing fog hangs over Vienna, softening the light of the street-lamps. There is snow on the ground, and the bare branches of the trees are tipped with frost. I am walking down Porzellangasse, a broad street in Viennas Ninth District. It is 7:00 P . M . The street is quiet, for most people prefer not to drive in this weather, the roads are too slick. The street is lined with buildings four or five stories high. They have changed little since the days before the First World War, when Vienna was one of the great cities of the world, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and that empire was a major power, surpassed only by Russia in the extent of the European territory over which it ruled. Its lands spread northeast as far as what is now Ukraine, east over todays Czech and Slovak Republics, and southeast through Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia to the fateful city of Sarajevo.

All of my grandparents lived in this city then. I knew only my mothers mother, Amalie Oppenheim, the sole survivor of the tragedy that overwhelmed Viennas Jews after the Nazi annexation of Austria. But tonight, pushing away the time that has passed since that calamity, I will begin to get to know one other grandparent. In a backpack I am carrying a stack of papersthey must weigh about fifteen poundsby and about my mothers father, David Oppenheim.

Included in this treasure trove of family history are more than a hundred letters my grandparents wrote to my parents, Kora and Ernst Singer, and to my mothers sister, then Doris Oppenheim, after they left for Australia in 1938. I have just collected them from Dr. Adolf Gaisbauer, director of the Library of the State Archives of Austria, who last year published some of them in a book called David Ernst Oppenheim: Von Eurem Treuen Vater David. The subtitle means from your faithful father David and is the way in which my grandfather closed his letters. Although I had long known of the existence of the letters, which Doris and my mother had carefully preserved, I had never read them. I can read German, but my grandfathers handwriting was difficult to decipher, and its legibility was not helped by the fact that the letters were often written on both sides of very thin paper. When my mother and Doris had, many years ago, read one or two letters to me, I had been busy with my work as a philosopher and bioethicist, writing and teaching about the ethics of our treatment of animals, and life-and-death decisions in the care of infants born with severe disabilities. I did not ask them to read me the other letters.