Vienna, Now and Then

January 1997

A freezing fog hangs over Vienna, softening the light of the street-lamps. There is snow on the ground, and the bare branches of the trees are tipped with frost. I am walking down Porzellangasse, a broad street in Viennas Ninth District. It is 7:00 P . M . The street is quiet, for most people prefer not to drive in this weather, the roads are too slick. The street is lined with buildings four or five stories high. They have changed little since the days before the First World War, when Vienna was one of the great cities of the world, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and that empire was a major power, surpassed only by Russia in the extent of the European territory over which it ruled. Its lands spread northeast as far as what is now Ukraine, east over todays Czech and Slovak Republics, and southeast through Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia to the fateful city of Sarajevo.

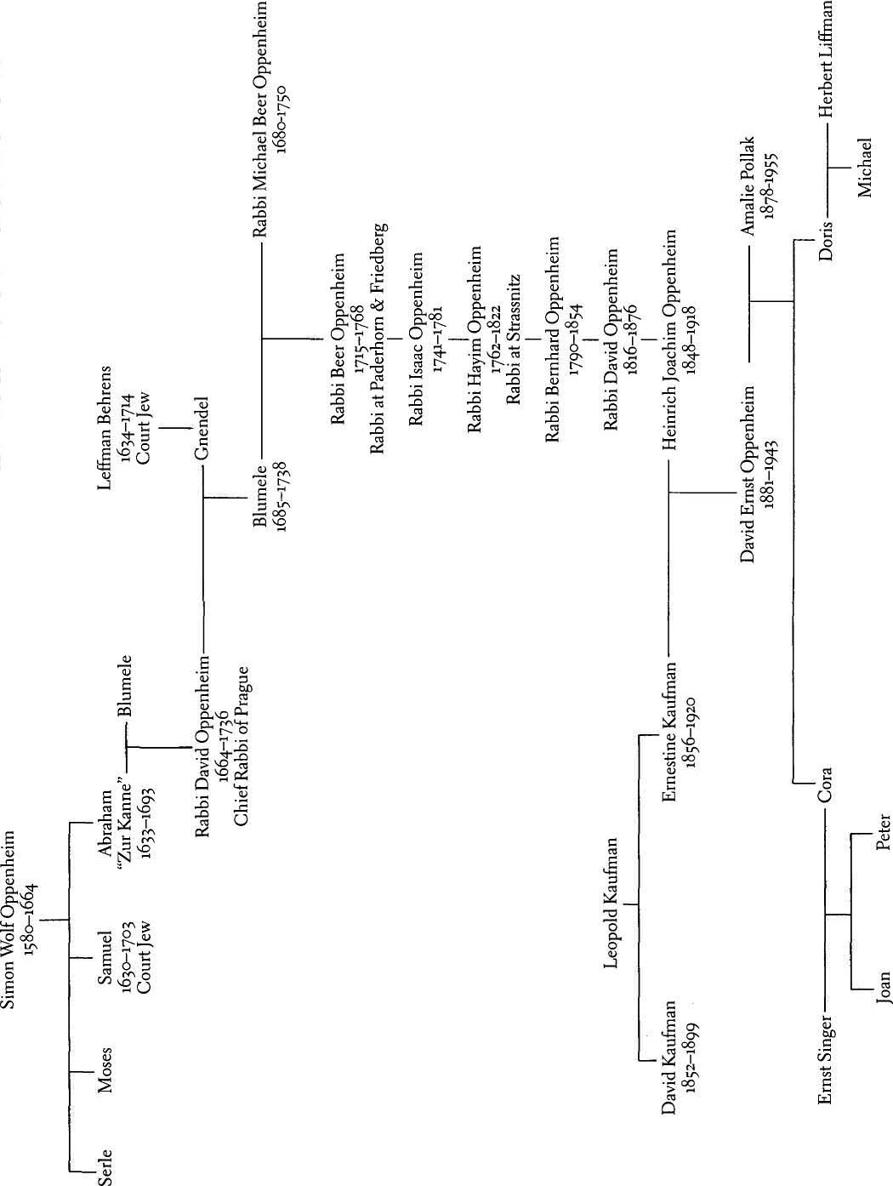

All of my grandparents lived in this city then. I knew only my mothers mother, Amalie Oppenheim, the sole survivor of the tragedy that overwhelmed Viennas Jews after the Nazi annexation of Austria. But tonight, pushing away the time that has passed since that calamity, I will begin to get to know one other grandparent. In a backpack I am carrying a stack of papersthey must weigh about fifteen poundsby and about my mothers father, David Oppenheim.

Included in this treasure trove of family history are more than a hundred letters my grandparents wrote to my parents, Kora and Ernst Singer, and to my mothers sister, then Doris Oppenheim, after they left for Australia in 1938. I have just collected them from Dr. Adolf Gaisbauer, director of the Library of the State Archives of Austria, who last year published some of them in a book called David Ernst Oppenheim: Von Eurem Treuen Vater David. The subtitle means from your faithful father David and is the way in which my grandfather closed his letters. Although I had long known of the existence of the letters, which Doris and my mother had carefully preserved, I had never read them. I can read German, but my grandfathers handwriting was difficult to decipher, and its legibility was not helped by the fact that the letters were often written on both sides of very thin paper. When my mother and Doris had, many years ago, read one or two letters to me, I had been busy with my work as a philosopher and bioethicist, writing and teaching about the ethics of our treatment of animals, and life-and-death decisions in the care of infants born with severe disabilities. I did not ask them to read me the other letters.

I learned more about my grandparents ten years ago, when Doris retired from her career as a social worker and wrote a masters thesis about her father. I returned it with a scribbled note:

Doris,

I read this with great interest. Congratulations on making your father live again. Now Id like one day to read his works myself, to see what parallels (if any) there are with my own views, despite our rather different fields, and intellectual backgrounds.

One sentence from Doriss summary of an essay my grandfather wrote on the Roman philosopher Seneca struck a particular chord with me. She described how her father distinguishes between the genuine philosopher, who aims to integrate his teaching and his life, and the theoretical professor, who is concerned only with his professional standing and personal reputation. This distinction resonated with me. I certainly hoped that I was a genuine philosopher, in this sense, and for the first time I wondered how much I had in common with this grandfather I had never known.

Nevertheless, my work in ethics continued to take priority over delving further into my grandparents life. So last year, when I read the selections from the letters in Dr. Gaisbauers book, I was reading them for the first time. They reached across nearly sixty years, and opened up a world that was closely linked with mine and yet utterly different from it. My parents were educated people, my father a businessman and my mother a doctor, but neither of them was a serious scholar, and they did not spend much time thinking about the big questionsabout understanding human nature, or how we ought to live. My career had seemed, to some, a surprising turnmy cousin Michael Liffman, Doriss son, once told me that of all the people he had known at university, I was the only one who had followed a path that he could not have predicted. By that he meant, I think, that he had expected me to go into my fathers business, or perhaps to practice law, like my sister. Instead, I had taken up philosophy. David Oppenheim, I now learned, wrote about fundamental values, and what it is to be human. Was my own life echoing that of a grandparent I had never known? That thought began to take hold of me, and would not let go. I had to find out whether, despite the different times and places in which we lived, there was something that bound us together.

At the end of Porzellangasse, I cross Berggasse, just a few doors from number 19, where Sigmund Freud had his home and his consulting rooms. Earlier in the day, seeking traces of my grandfather, I had visited Freuds rooms, now a museum. Here the famed Wednesday Group, more formally known as the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society, met. My grandfather became a member of the group in January 1910, and attended its meetings for nearly two years. On April 20, 1910his twenty-ninth birthdayhe gave a presentation entitled Suicide in Childhood to a group of sixteen people, including Freud and most of the regular members of the society. His paper was a great success, stimulating so lively a conversation that the group voted to publish a pamphlet including Davids talk and the ensuing discussion. Quite a birthday present for a young high school teacher! As I left Freuds rooms, I imagined my grandfather walking down those same steps in a state of elation. As a talented young scholar with whom Freud was eager to collaborate, he appeared to have a bright future ahead of him. Yet within eighteen months my grandfather had parted from Freud, following instead the first of the great heretics of psychoanalysis, Alfred Adler. In opposition to Freuds insistence on unconscious sexual desire as the key to understanding human behavior, Adler developed the idea of the inferiority complex, and saw the drive to gain power, as compensation for a sense of inferiority, as more significant. Why, I wondered, did David take the decision to side with Adler, knowing that this must mean the end of all further contact with Freud?