Praise for Peter Singer and

The Most Good You Can Do

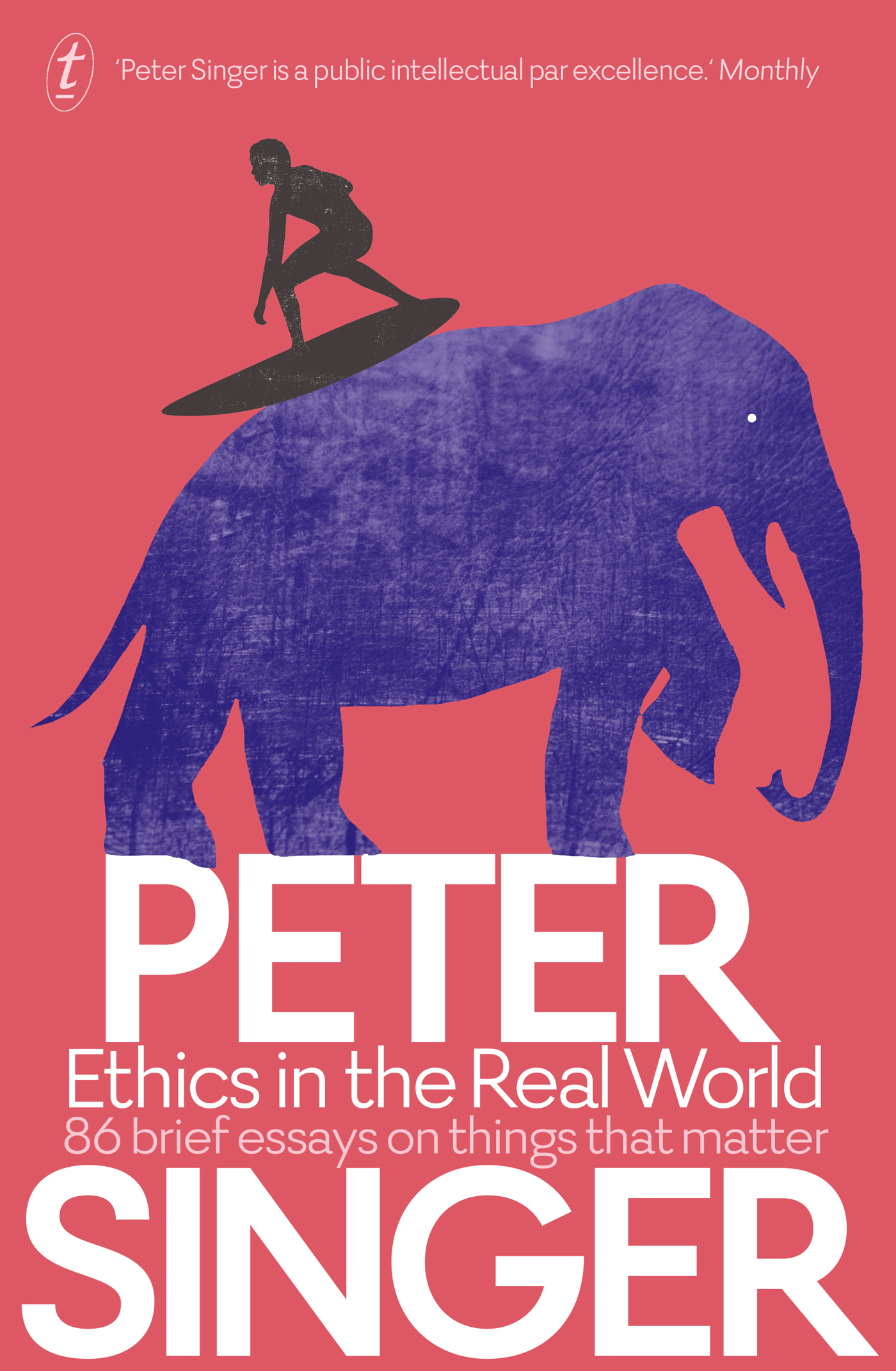

Peter Singer is a public intellectual par excellence; he takes complex philosophical notions and relates them directly to the general reader without a hint of loftiness or superiority.

MONTHLY

Peter Singers status as a man of principles and towering intellecta philosopher extraordinaire, if you willis unrivalled in Australia.

SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

Peter Singer may be the most controversial philosopher alive; he is certainly among the most influential.

NEW YORKER

Singer makes a strong case for a simple ideathat each of us has a tremendous opportunity to help others with our abilities, time and money. The Most Good You Can Do is an optimistic and compelling look at the positive impact that giving can have on the world.

BILL AND MELINDA GATES

The Most Good You Can Do is an important book. Reading it may change your life and save someone elses.

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW

Forty years on from Animal Liberation, Peter Singer is still challenging our complacency with his advocacy for new ideas and movements...In clear prose, Singer weaves effective altruism into a timely and convincing ideology.

BOOKS+PUBLISHING

Other books by Peter Singer

Democracy and Disobedience

Animal Liberation

Practical Ethics

Marx

Animal Factories (with Jim Mason)

The Expanding Circle

Hegel

The Reproduction Revolution (with Deane Wells)

Should the Baby Live? (with Helga Kuhse)

How Are We to Live?

Rethinking Life and Death

The Greens (with Bob Brown)

Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement

A Darwinian Left

Writings on an Ethical Life

Unsanctifying Human Life

One World

Pushing Time Away

The President of Good and Evil

How Ethical is Australia? (with Tom Gregg)

The Ethics of What We Eat (with Jim Mason)

The Life You Can Save

The Most Good You Can Do

Peter Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946, and educated at the University of Melbourne and the University of Oxford. He is Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University and Laureate Professor, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, at the University of Melbourne.

An internationally renowned philosopher and acclaimed author, Peter Singer was named one of the worlds 100 most influential people by Time magazine in 2005.

He divides his time between New York City and Melbourne.

www.princeton.edu/~psinger

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright Peter Singer 2016

The moral right of Peter Singer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in the USA 2016 by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

This edition published in 2016 by The Text Publishing Company.

Cover design by Text.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication

Creator: Singer, Peter, 1946 author.

Title: Ethics in the real world : 86 brief essays on things that matter / by Peter Singer.

ISBN: 9781925355857 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925410228 (ebook)

Subjects: Ethics. Ethical problems. Essays.

Dewey Number: 170

CONTENTS

WE ALL MAKE ETHICAL CHOICES, often without being conscious of doing so. Too often we assume that ethics is about obeying the rules that begin with You must not.... If that were all there is to living ethically, then as long as we were not violating one of those rules, whatever we were doing would be ethical. That view of ethics, however, is incomplete. It fails to consider the good we can do to others less fortunate than ourselves, not only in our own community, but anywhere within the reach of our help. We ought also to extend our concern to future generations, and beyond our own species to nonhuman animals.

Another important ethical responsibility applies to citizens of democratic society: to be an educated citizen and a participant in the decisions our society makes. Many of these decisions involve ethical choices. In public discussions of these ethical issues, people with training in ethics, or moral philosophy, can play a valuable role. Today that is not an especially controversial claim, but when I was a student, philosophers themselves proclaimed that it was a mistake to think that they have any special expertise that would qualify them to addresses substantive ethical issues. The accepted understanding of the discipline, at least in the English-speaking world, was that philosophy is concerned with the analysis of words and concepts, and so is neutral on substantive ethical questions.

Fortunately for mebecause I doubt that I would have continued in philosophy if that view had prevailedpressure from the student movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s transformed the way moral philosophy is practiced and taught. In the era of the Vietnam War and struggles against racism, sexism, and environmental degradation, students demanded that university courses should be relevant to the important issues of the day. Philosophers responded to that demand by returning to their disciplines origins. They recalled the example of Socrates questioning his fellow Athenians about the nature of justice, and what it takes to live justly, and summoned up the courage to ask similar questions of their students, their fellow philosophers, and the wider public.

My first book, written against the background of ongoing resistance to racism, sexism, and the war in Vietnam, asks when civil disobedience is justified in a democracy. Since then, Ive very largely sought to address issues that matter to people outside departments of philosophy. There is a view in some philosophical circles that anything that can be understood by people who have not studied philosophy is not profound enough to be worth saying. To the contrary, I suspect that whatever cannot be said clearly is probably not being thought clearly either.

If many academics think that writing a book aimed at the general public is beneath them, then writing an opinion piece for a newspaper is sinking lower still. In the pages that follow you will find a selection of my shorter writings. Newspaper columns are often ephemeral, but the ones I have selected here discuss enduring issues, or address problems that, regrettably, are still with us. The pressure of not exceeding 1,000 words forces one to write in a style that is not only clear but also concise. Granted, in such essays it is impossible to present ones research in a manner that can be assessed by other scholars, and inevitably some of the nuances and qualifications that could be explored in a longer essay have to be omitted. Its nice when your colleagues in philosophy departments appreciate what you are doing, but I also judge the success of my work by the impact my books, articles, and talks have on the much broader audience of people who are interested in thinking about how to live ethically. Articles in peer-reviewed journals are, according to one study, read in full by an average of just ten people. An opinion piece for a major newspaper or a syndicated column may be read by tens of thousands or even millions, and as a result, some of them may change their minds on an important issue, or even change the way they live. I know that happens, because people have told me that my writing has changed what they donate to charity, or led them to stop eating animal products or, in at least one case, to donate a kidney to a stranger.

Next page