Published by Otago University Press

PO Box 56 / Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

Fax 64 3 479 8385

Email:

First published 2011

Copyright Liz Lightfoot 2011

ISBN 978-1-877578-08-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859227-5 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859228-2 (Kindle)

ISBN 978-1-98-859229-9 (ePdf)

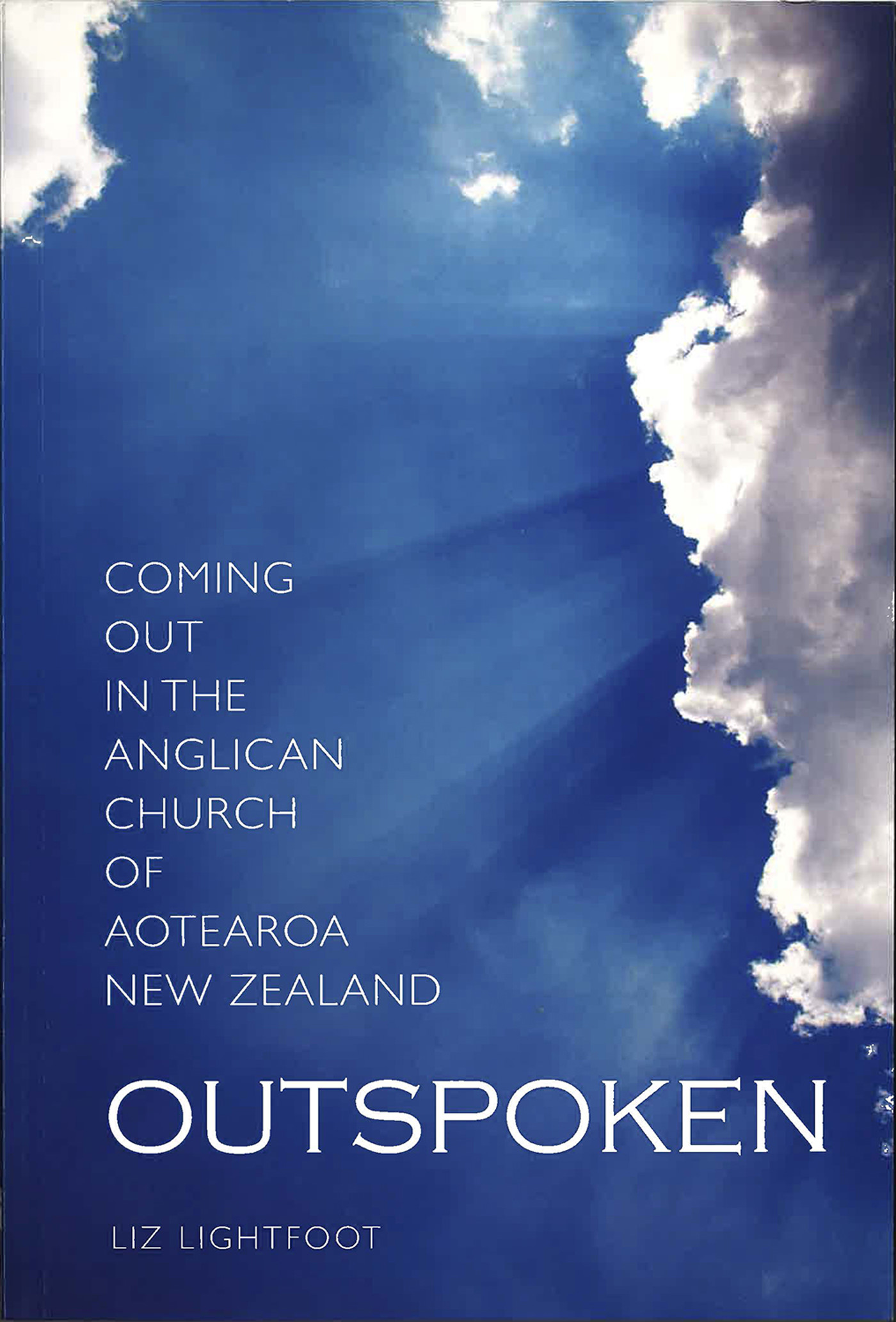

Cover image Andreea Manciu/istockphoto.com

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

CONTENTS

I n 2007, I underwent a crisis of sexual identity. I was married, with two young children, when I became attracted to another woman. While that attraction did not lead to any other action, it triggered the end of my marriage. The hostility I encountered at the Anglican church I was attending made me curious and concerned about other peoples experiences. I wondered what kind of reaction someone who has a partner of the same gender might elicit in the Church and what impact that might have on a persons life and faith.

I decided to return to the middle-to-high Anglican church I had earlier been a part of and found worshipping there to be a source of great strength and healing. Fortunately, I had encountered a broad spectrum of approaches to worship and doctrine within the Anglican Church. On reflection, I wondered how my faith might have been affected if evangelical or literalist Anglicanism had been the only Christian world I had known and where that might have left me with regard to my faith community.

At my church I exercise a ministry as a liturgist. This involves leading the congregation in the prayers of confession and intercession and administering the chalice. It is an immense privilege, accompanied always regardless of how I am feeling by a sense of Gods presence.

Most liturgists in the Anglican diocese in which I live are licensed; I am not, but it occurred to me to ask what the process would involve. Would the same restrictions that apply to those who have a call to the ordained ministry apply to liturgists, who are considered lay people? Would I have to be either in a heterosexual marriage or celibate? If I were to enter a same-sex relationship, would I have to relinquish my licence and duties? The answer was that if I did enter a same-sex relationship, I would not be able to continue as a licensed liturgist. I could occasionally, at my vicars discretion, say some prayers or read a lesson, but I would not be able to administer the chalice.

Soon after this experience, I became privy to the stories of several Christians in similar situations. Their stories illustrated the painful and long-lasting damage that coming out in the Church can have on ones psyche. Others I spoke with had more positive experiences. It seemed to me imperative that stories of being gay in the Church be heard, especially in the context of the current maelstrom within the worldwide Anglican community, in which the Church has been encouraged to undergo a listening process.

Encouraged by others to gather the stories of gay and lesbian people in the Church, I looked into the possibility of doing that as part of a university degree. One academic I talked to was Dr John Paterson, who was then Chair of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Waikatos Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, and who teaches research methodology and regularly supervises graduate research projects. John has roots in Christianity and an interest in issues of social justice. I knew that I wanted to do the project under his supervision but academic regulations prohibited me from doing even an Honours-level paper in his department. In the end, with the help of a scholarship from Te Kotahitanga, the Trust Board of St Johns Theological College, I undertook the study independently, not as part of a degree. Dr Paterson kindly offered to supervise this project and to provide me with advice throughout.

From the outset, things have fallen into place. It is as if the research was waiting to be done and thanks to a strange, unplanned and completely unanticipated sequence of events both personally and with regard to people who have crossed my path, it has proved possible to do it. Nonetheless, I could not have begun the work without the guidance, support and encouragement of Dr Paterson and the unflagging back-up of cheerleading friends and family in New Zealand and well beyond. I gratefully thank and acknowledge each one of them.

Aims

Some truths are not worth the pain they cause. Others might be necessary for the pain they can prevent. Herbert & Irene Rubin, Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data

By presenting a number of personal histories of the experience of coming out as a lesbian or gay person in the Anglican Church of Aotearoa New Zealand, my intention is to give voice to those most affected by the debate in this country. My application to Te Kotahitanga stated:

The aim is to document typical stories as well as to provide some indication of the variety of participants experiences. I will work to let participants stories be heard from their own perspective, as a contribution to the listening process upon which the Anglican Communion is embarked.

I am interested in such dimensions as the individuals place in the Church, the role of the local church community, the meaning of Christian commitment in relation to sexual identity, experiences of support and tension, and the impact on the participants relationship with God and on their involvement with the Church.

I hope thereby also to contribute to the thinking about pastoral care by conveying the implications of the outworking of a range of theological stances on the lives and faith journeys of lesbian and gay people.

Peoples lives are sacred ground. The area of sexuality is one where people are arguably at their most vulnerable. In the Anglican Communion, fractured as it is by disagreements on this topic, it is my hope that this research will constitute a community-building exercise.

Preparation

At the beginning of 2009 I undertook an intensive two-month course in research ethics and methodology under the direction of Dr Paterson. The principal ethical concerns were to ensure the protection of participants and to give participants control over their stories. After determining the aims, ethical framework and scope of the research, I wrote an introductory letter outlining the project (see Appendix). I asked the coordinator of the New Zealand branch of Changing Attitudes, a group drawn by Gods love to work for the full inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the Anglican Communion, to circulate an email request for participants in a project in which I wished to interview people about their experience of coming out in the Anglican Church in New Zealand. One person on the list contacted two people he knew, of whom one decided to participate. Another list member got in touch with me directly. Two members of clergy reprinted the ad in their pew sheet, with one contacting me:

Before I use my position to send your request to gay and lesbian members of the congregation I need assurance that their stories will be heard sympathetically and non-judgementally. (The opposite unfortunately has happened in the past even though supposedly under the direction of a university.) In short, I need someone to vouch for you.

I referred the clergyperson to my vicar, who provided a phone reference.

Next page