As when the Sun, new risen,

Looks through the horizontal misty air,

Shorn of his beams, or from behind the Moon,

In dim eclipse, disastrous twilight sheds

On half the nations, and with fear of change

Perplexes monarchs.

Milton, Paradise Lost, 1667

Storms at sea, as well as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, are possibly the only other natural phenomena which affect people like a total solar eclipse, never to be forgotten. In the case of a solar eclipse, it affects them even though no threat whatsoever emanates from it. Calculated a long time in advance with plenty of notice, the celestial spectacle takes place and yet people are still shocked and deeply touched by the silent immensity of the Sun being covered by darkness. We ourselves become as quiet and speechless as nature surrounding us: no dog barks, no birds sing when the greenish-grey darkness of the core shadow of the Moon falls across the landscape and the sky becomes so dark that planets and bright stars become visible during the day.

One would have to be a poet in order to be able to express the strong and changing feelings provoked by a solar eclipse, which is why the words of Wordsworth and the report of the last visible solar eclipse in Central Europe by Adalbert Stifter are included at the end of this little book. Anyone who has ever experienced a solar eclipse will see no pathos in the words of the Austrian writer.

It is easy to understand that, in earlier times, people were filled with fear and terror by a solar eclipse, because in ancient Greece, for example, only a few educated people understood the astronomical circumstances leading to an eclipse. The theft of the sunlight by the Moon suddenly called into question the goodness and divinity accorded to the Sun in religious experience. The Moon turned into a dragon which devoured the Sun that is how many ancient cultures thought about the eclipse. Yet why are we still affected just as strongly today, in a time when everyone understands the astronomical details to a greater or lesser extent and everything can be explained?

It is because, in the same way as an earthquake, the secure foundation of our existence is suddenly called into question for a short period of time: in this instance, the certainty that the Sun shines during the day. We may object that it simply becomes night for a brief period of time, but that is to miss the point. The kind of darkness which arises during a solar eclipse is not the kind of darkness we know from night. It has nothing of the romantic mood of a beautiful dusk. It is a greenish light, sallow and strangely oppressive, in which the visible veil-like ring of rays of the Suns corona thrones majestically above the lowering atmosphere.

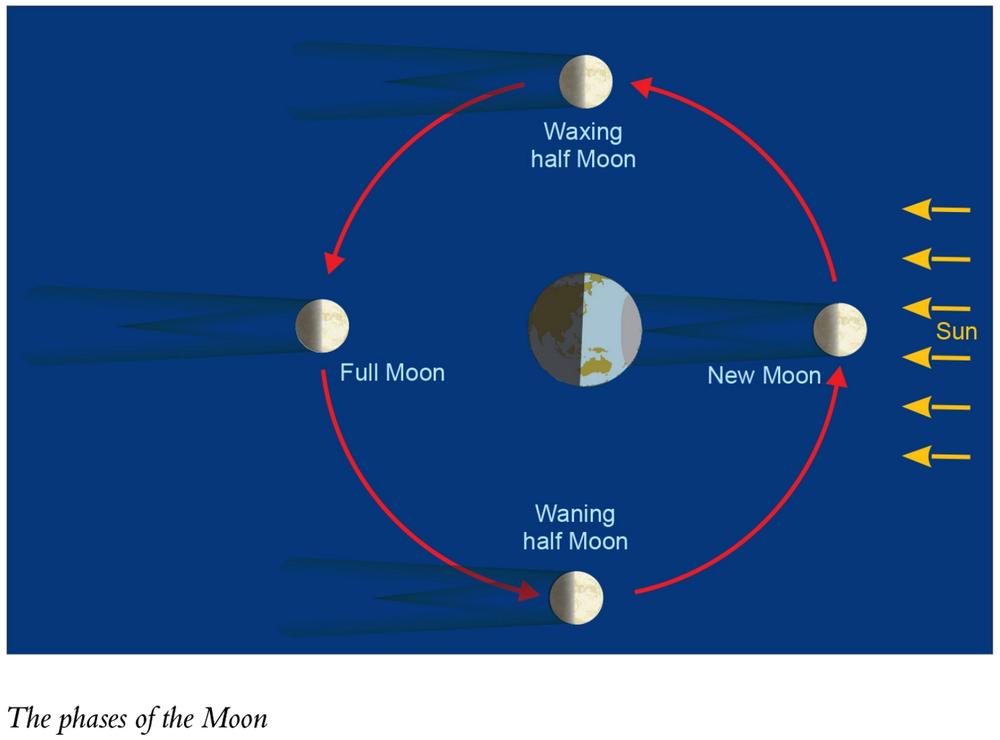

To understand a solar eclipse, we need to understand the movement of the Moon. The different phases of the Moon come about as it moves around the Earth. If the Moon is next to the Sun, its a New Moon. If its positioned at right angles to the Sun, its a waxing and waning half Moon. If its opposite the Sun, its a Full Moon. The name New Moon is, however, misleading because the Moon is not yet new. In fact, in antiquity the New Moon designated the small lunar sickle when the Moon was visible again for the first time in the evening sky as a New Moon. The Roman priests proclaimed the new month when they saw the New Moon. The word calendar is reminiscent of this, since calere means to call. In this respect the New Moon should actually be called the non-moon.

Total and annular solar eclipses

A solar eclipse occurs when the shadow of the Moon falls on the Earth. Two different shadows are actually created the core shadow or umbra, and the half shadow or penumbra. If we, standing on the Earth, are positioned within the core shadow, the Sun appears completely covered. This is a total solar eclipse, and its range can be up to 165 miles (270 km) wide. The movement of the Moon means that, in the course of an eclipse, the umbra sweeps a path of darkness across the Earth. Outside this core zone, in the range of penumbra, the Sun appears partially covered by the Moon. The diameter of the penumbra is approximately 4,500 miles (7000 km).

It is one of the mysteries of the planetary system that the Sun and the Moon display correlations which can hardly be coincidence: for example, the Moon takes 29.5 days to move from Full Moon to Full Moon, which is almost the same amount of time as the Sun requires on average for one rotation around its axis. The Moon thus reflects not only the light of the Sun, but also its type of movement.

A second correlation between Sun and Moon lies in their size in the sky: although the Sun with a diameter of 865,000 miles (1,390,000 km) is approximately 400 times as big as the Moon at 2159 miles (3476 km), both appear to be the same size when looked at from Earth. The Moon, with its average distance from the Earth of 238,600 miles (384,000 km) is thus 400 times closer than the Sun.

However, the distance between the Moon and the Earth fluctuates due to the elliptical path of the Moon around the Earth. At apogee (furthest from Earth), the distance is about 221,462 miles (356,410 km) and at perigee (closest to Earth) about 252,711 miles (406,700 km). This means that the distance of the Moon moves by one seventh. It is worth trying to visualize this difference in size by comparing the Full Moon when close to and distant from the Earth. Since the height of the Moon above the horizon influences the impression of size, try this when Moon is as high as possible. The problem is that the Full Moons at perigee and apogee lie approximately half a year apart. Nevertheless, we may become more aware that the Full Moons from December 2016 to March 2017 are particularly large, and in summer (May, June, July) 2017 are particularly small.

But it is not only the Moon which fluctuates in its distance and thus in its size when seen from the Earth. Since the Earth also moves in an ellipse around the Sun, even if it is less elongated, the distance between the two and thus the apparent size of the Sun also change. The distance between Sun and Earth ranges between 91 and 94 million miles (147 and 151 million km) in the course of the year, so correspondingly the apparent diameter of the Sun changes by 3%. This fluctuation is four times smaller than the fluctuation in diameter of the Moon, but it contributes to the complexity of time and character of solar eclipses.

In optimum conditions, that is, when the Moon is at perigee and the Sun at apogee, the tip of the umbra cone projects an umbra which is 165 miles (270 km) wide. In the opposite case, when the Sun is large (perigee) and the Moon is relatively small (apogee), the shadow cone does not reach the surface of the Earth. Instead of a total eclipse, an annular one occurs in which the Moon is surrounded by a ring of light. In such a case the remaining brightness is so great that the corona described above cannot be seen, but the ring of light around the Moon, which shimmers in an anthracite colour, is still a breathtaking sight.

The rhythm of solar eclipses

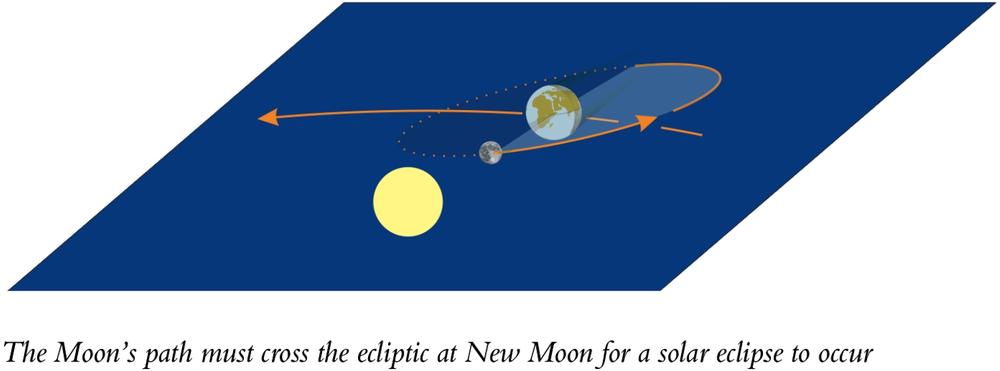

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon casts its shadow on to the Earth, but why does this not happen at every New Moon when the Moon is between the Earth and the Sun?

The path of the Moon is inclined by 5 to the Earths. The angle of its path means that the Moon, as a rule, travels above or below the Sun as it passes. As a consequence its shadow mostly does not fall on the Earth but passes above or below it.