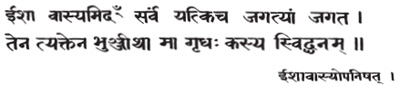

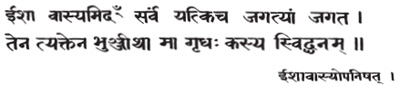

I In a world where everything changes [where nothing is permanent] the divine is everywhere present [in flowers, birds, animals, in forests, in man].

II Enjoy fully what the god concedes to you and never covet what belongs to others [neither their goods, nor their talent, nor their success].

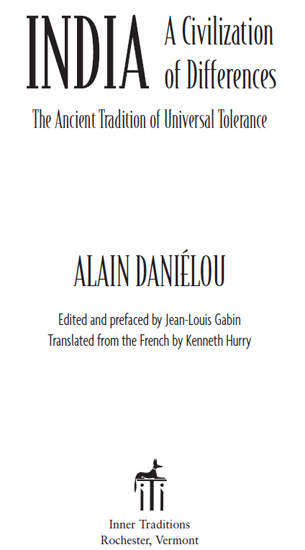

ISHA UPANISHAD, TRANSLATED BY ALAIN DANILOU

FOREWORD

Caste and Freedom for Alain Danilou

C aste problems reared their head in Alain Danilous family before his birth. Indeed, his mother belonged to the Clamorgan family, one of the most ancient noble families in Normandy, some of whose members were crusaders. The father of Madeleine Clamorgan was, according to the traditions of his caste, a general in the French Army. She herself was a devout Catholic and devoted to Pius X.

The Danilou family, on the other hand, was non-religious, with neither glorious family traditions nor noble title. Alain Danilous grandfather, the Mayor of Douarnenez, was buried without religious rites, a fact that was scandalous and very rare at that time. Charles, Alains father, had not been baptized when he met his wife. A member of Parliament, he became the leader of the parliamentary radical party, a movement that was considered to belong to the extreme left. In the thirties, at Chteaulin, a tiny sub-prefecture and Danilous constituency, one of my distant relations, Guillaume Laurentknown familiarly as Tonton Laoucwas his electoral agent. They defended secularism and the state schools and violently fought against the clergy and the Catholic movements at a time when the school war was raging in Brittany. They were the Reds against the Whites.

Curiously enough, it was the Dreyfus affair that brought together Alain Danilous parents, persons not very likely to meet. On the subject of this racist affair that divided French opinion, they both declared in the Captains favor, which may seem evident for Charles, but was much less so for Madeleine, a soldiers daughter.

Very early on, Alain Danilou became aware of the strange nature of this marriage and the problems it raised. In his memoirs, he writes about his mother: The truth was that my mother thought of her children as bastards; because she was an uncompromising woman, she must surely have faced that problem at some point in her life. She always refused to introduce us into her world, nor could she bear to see us mingle with her husbands political friends....

In 1926, Alain Danilou spent a year at Saint Johns College in Annapolis, Maryland. He was amazed at the profound racism he encountered in the United States: the Blacks were relegated outside the towns; he was briskly reprimanded by the college dean for having spent the weekend at the home of a Jewish friend.

In 1930, a study trip to Algeria was cut short because the local colonials looked disapprovingly on this Parisian who frequented the natives on an equal footing, the height of dissidence!

His set of articles, Le Tour du monde en 1936, gives us a better glimpse of Alain Danilous ideas at that time. Speaking about Harlem, where he saw Macbeth played by a Negro cast, he wrote: Shakespeare corrected, arranged, erased by these Negroes, I feel a racial prejudice within me I should never have thought myself capable of.... Harlem is boring; I dream of the beauty, the refinement, the poetry of other colored peoples, in the dazzling Indies.

On the American Indians, of whom he was a passionate defender, he wrote: They contemplate this last defeat: the conquerors, covered with their spoils, ridiculously imitating the dances they danced for the gods.... A gust of civilization reaches us like the desert wind when, in the middle of all the pretentious and vulgar junk of imitation products, these objects appear, in which every detail is noble, each line of which has been pondered for centuries.

This first work of his, written in 1936, gives us a foretaste of the orientation of his work, and the great idea that he ceaselessly pursued. Dazzled by India, its level of culture and its arts, he devoted his life to obtaining world recognition for the great civilizations of Asia and to showing that Western economic imperialism should not be tied to any kind of cultural imperialism. He never ceased in his struggle to get the West to understand that, for example, the gagakuthe orchestra for traditional music at the Japanese courtwas comparable to the Berlin Philharmonic, and that the raga interpretations of Ravi Shankar are not folklore, but artistic works in no way inferior to those of Mozart, Ravel, or Bernstein. He started with the musical worldto win recognition for the values of an art little known in the Westand then extended his scope to include other sectors.

He decided which side he was on very rapidly and, at Benares, became a native, violently anticolonial, connected with the orthodox independence movements, to the amazement and reprobation of the occupant British community. He even accepted the designation of mleccha, which in Hindi means a barbarian, one who has not been born on the sacred soil of India. In traditional Indian society, the foreigner, whatever his origin, is classed as a Shudra, that is, as belonging to the artisan and workers caste, which is by far the most numerous, since it includes about eighty percent of the entire population.

As Alain Danilou explains in his memoirs, this statuswhich was his for many long yearsis in no way an obstacle to the gaining of knowledge. He was able to study with the pandits, the Brahman scholars of Benares, so long as he observed the duties of a good Shudra student: vegetarianism, which is not usual for members of this caste; daily ritual bathing in the Ganges; not touching his master; not entering certain parts of his masters house; and so on.

Having become the disciple of the scholarly monk Swami Karpatri, Danilou spent many years studying traditional cosmology and metaphysics with Pandit Vijayanand Tripathi and the rudra vina with Sri Sivendranath Basu. At the order of Swami Karpatri, he was regularly initiated into Hinduism and received the name of Shiva Sharan (the protected, or protg, of Shiva).

After plunging into the orthodox Hindu world (learning Hindi and Sanskrit and studying philosophy) he became a Hindu himself and returned to Europe to show the West the true face of Hinduism. This orthodoxywhich he made his ownis totally opposed to puritanism, of which his later translation of the Kama Sutra is living proof.

He shocked people by his ideas, which separated him from what was in fashion. The Aryan invasions, the barbarian hordes from the north, were for him the end of the golden age of the great civilizations. He opposed the later moralist religions, starting with Buddhismwhich he castigated for its proselytismand in particular the monotheistic religions, Islam and Christianity. Marxism and socialism he considered as pernicious utopias. His Shaivite approach to Hinduism also put him against many Indian circles, which have become, thanks to Western influence, puritan and integralist, contrary to the true spirit of this tradition.

Another problem arose owing to his homosexuality, which he did not hide. He rapidly detached himself from his family and, during his Paris years, led a bohemian life, getting to know Gide, Cocteau, Jean Marais, and even the dancers of the Moulin Rouge: a whole society of suspects that were not very commendable in his familys eyes. From the end of the fifties, he supported Arcadia, one of the first homosexual movements in Europe.

Next page