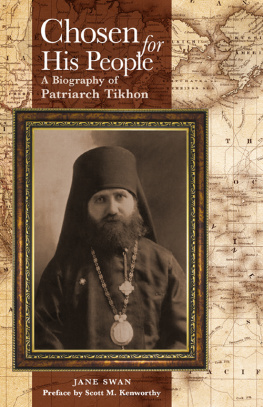

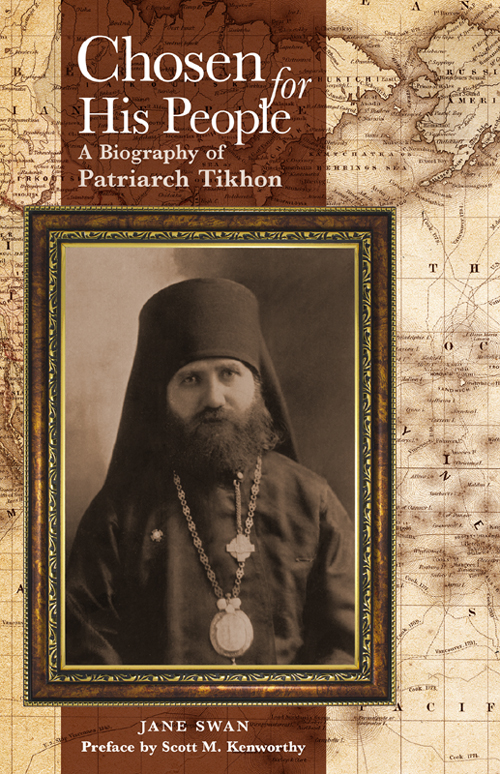

Chosen for His People

A Biography of Patriarch Tikhon

by Jane Swan

Preface by Scott M. Kenworthy

H OLY T RINITY S EMINARY P RESS

Holy Trinity Monastery

Jordanville, New York

2015

Printed with the blessing of His Eminence, Metropolitan Hilarion, First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

Chosen for His People: A Biography of Patriarch Tikhon, 2nd Edition

2015 Holy Trinity Monastery

An imprint of

H OLY T RINITY P UBLICATIONS

Holy Trinity Monastery

Jordanville, New York 13361-0036

www.holytrinitypublications.com

First Edition: A Biography of Patriarch Tikhon

1964 Holy Trinity Monastery

ISBN: 978-1-942699-02-6 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-942699-03-3 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-1-942699-04-0 (Mobipocket)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933221

Scripture passages taken from the New King James Version.

Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission.

Deuterocanonical passages taken from the Orthodox Study Bible.

Copyright 2008 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission.

Psalms taken from A Psalter for Prayer, trans. David James

(Jordanville, N.Y.: Holy Trinity Publications, 2011).

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

PREFACE

S t Tikhon (Bellavin, 18651925), Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia from 1917 to 1925, was one of the most important figures in twentieth-century Orthodox Church history. Moreover, as head of the largest nongovernmental institution in Russia at the time of one of the twentieth centurys pivotal eventsthe Russian Revolutionhe is a key figure in modern world history. It is a remarkable fact, therefore, that Jane Swans book, originally published half a century ago, remains the only English-language biography. When Swan wrote her doctoral dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania in 1955, which was published as A Biography of Patriarch Tikhon in Jordanville in 1964, the sources available were quite limited. The main sources that Swan used consisted of migr accounts such as those by Metropolitan Anastassy, Archimandrite Constantine (Zaitsev), Protopresbyter Michael Polsky, and others; and accounts by Western observers, some of whom (like W. C. Emhardt) were supportive of the Russian Church, but others, such as Matthew Spinka (professor of church history at Hartford Seminary) and Julius Hecker, tended to be quite critical of the Church. Swan also utilized primary sources, especially St Tikhons own proclamations as well as Soviet newspaper reports. Not many new sources became available until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Since the fall of communism, there has been a burgeoning interest in Russia both in the person of St Tikhon and in the fate of the Orthodox Church during the Revolution. This, combined with greater access to archival documents (especially in the late 1990s), resulted in very significant publications, including a massive volume of documents gathered by the secret police (Cheka/GPU) as it prepared the trial against the patriarch. Russian scholars have also written biographies and more specialized monographs about St Tikhon or particular aspects of his life, both before and after the Revolution. It is therefore possible to know much more now than half a century ago when Swan published her book. It is possible to answer with much greater certainty long-standing questions, such as the governments motivations behind the confiscation of church valuables and involvement in the Living Church schism in 1922, what precipitated the patriarchs change of course in 1923, and the circumstances around his death and last will. All of this requires an entirely new and thorough investigation.

Nevertheless, Swans book remains the only biography available in English, and it has stood the test of time. It is particularly valuable because it presents in English many of St Tikhons key epistles and addresses, as well as documents from the Soviet side. There are, to be sure, some inaccuracies and factual errors, especially about his early life and his family, which have been indicated in the notes of the current edition. Recent scholarship has not overturned her key insights, however, but in many cases has strengthened them. Her presentation of the intent of St Tikhons harsh criticisms of the Soviet regime in 1918, for example, is an important corrective to much western scholarship, which tended to accept the Soviet accusation that his actions were counter-revolutionarythat is, intended to overthrow the regime. She also presents a nuanced portrayal of the patriarch willing to make certain compromises with the Soviet regime by 1923 in order to preserve the Church from total fragmentation from within, while at the same time not completely capitulating to the demands of the regime. In the former, as in the latter, Swan argues, St Tikhon was guided by the same principle: while not interfering in politics, that the Church and its unity must be protected above all else.

Scott M. Kenworthy

Miami University

CHAPTER 1

Years of Preparation

I n 1865, the town of Toropets in the province of Pskov was almost untouched by any of the advantages or disadvantages of the modern era. The nearest railroad was 200

The family of Bellavin had long been connected with the Church. Vasilys father was a priest who had spent his entire life at Toropets and, as was the custom, his sons also would be expected to enter the priesthood. was a town bathed in religious atmosphere. Churches set the keynote. It could be compared to Moscow, for both were ancient, both were primarily religious strongholds and towns only as an afterthought, and both contained famous relics to which pilgrims continually flocked.

Except for the bare outlines of schooling, one would die a youth, and one would be brought back to Toropets, and Vasily would become great.

In 1878, Vasily entered the Pskov Seminary. Seminaries in Russia provided free religious training for future priests. Seminary education was usually the end of a priests formal schooling and was finished when the student was twenty years old. A few of the most brilliant students were elected to continue their studies at one of the four academies in Russia. These men were trained as learned theologians and professors, and often, after taking vows, they became bishops.

Vasily was one of the few selected to enter the Theological Academy at St Petersburg, where he went in 1884 at the age of nineteen. Because the normal age at entrance was twenty years old, his early admission attested to his superior scholastic abilities. From almost the beginning of his studies, his comrades affectionately nicknamed him Patriarch.