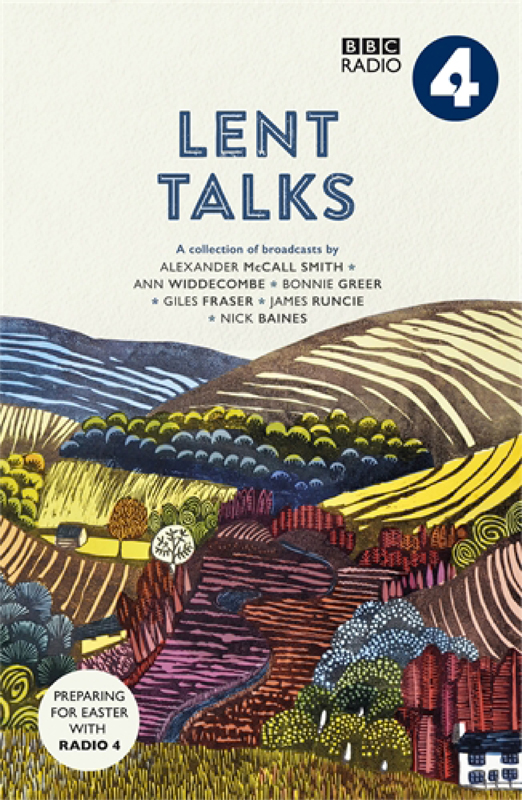

LENT TALKS

LENT TALKS

Preparing for Easter with Radio 4

BBC Radio 4

Stories provide a vehicle for learning about life, its richness and its depths, but when stories become too familiar, there is a risk that they cease to have the impact on us they had when we first encountered them. Thats even true of the stories of the temptation, trials and death of Jesus Christ stories that have been told over and over throughout the season of Lent for two millennia now.

What the BBC Radio 4 Lent Talks do each year is retell those stories through the eyes and experiences of a series of stimulating contemporary speakers and writers. Listening to them tell of their thoughts and feelings, passions and reflections, we see how those familiar stories play out in and resonate with the lives of individuals from our own time. In this way, key events in the life of Jesus take on a vivid, up-to-date dimension.

At the heart of the season of Lent is a story that is dramatic and rich in themes, but its not an easy setting for a non-Christian audience: self-denial, introspection, temptation, betrayal and abandonment against a background of supernatural events. Yet Lent is a season that encompasses some of the most profound dimensions of the human condition, and these talks help to bring that home. As with so many things in life that are demanding or require perseverance, Lent can be a time of increased self-knowledge.

For a broadcaster, the challenge is to speak to a general audience that consists of people of all faiths and none, and so the group of writers in this book represent a rich mix to illuminate the themes. In broadcast terms, such single-voice talks can be the hardest thing to get right. The presenter has to hold the listeners attention for 14 minutes with an engaging style and delivery and, most important, offer something that will linger in the mind long after the broadcast has ended.

This volume offers some vivid examples of that. The writer, director and literary curator James Runcie, author of the series The Grantchester Mysteries, draws on his know-how as a crime writer to view Christs Passion in the light of that expertise. He says, Crime writing... gives the author the opportunity to put characters under extreme pressure and see how they react to the continual threat of death and disaster.

The playwright Bonnie Greer reflects on Jesus silence before Pilate and asks, Why did he not defend himself? She finds an answer in the story of the character Solomon Northrup in 12 Years a Slave , who demonstrates the power of silence to name ones own terms. She concludes, there is power, too, in not speaking.

Ann Widdecombe explores the events from the perspective of a politician. She contemplates the business of making choices that are freely, bravely arrived at. She suggests that Jesus, in his decision to go to the cross and the devastating effect of that on his family and friends, offers a fearful reminder that we must be prepared to let people down, to disappoint those whom we love, to refuse to live up to the expectations of others if by doing so we do what is right.

For a while, Giles Fraser thought that he might become a chaplain in the army. It was a daunting call and, reflecting on it in the 2010 series, he dwells on what might be asked of him and whether or not his faith would survive the first-hand experience of so much suffering in what he likens to a parallel of Christs Holy Week, which is a searching audit of our moral courage.

Alexander McCall Smith, the author of The No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency series, taps into the abandonment many feel when they get older and ponders what Christianity has to say about fairness and forgiveness. Nick Baines, writing against the backdrop of the 2011 riots in Croydon, where he had been bishop, explores how we live with ourselves and one another; how we love and hate; who we love and hate and the values and core beliefs that reflect and challenge both the individual and the community.

Lent is a season that showcases the strengths and frailties of humanity. It explores the reason were alive here today. It is a time of temptation and trial that confronts us with how we must wrestle with what is ahead and prepare ourselves perhaps to be tested to the limit. But it is also a time of reassurance for humanity. For those seeking a spiritual connection with God, it offers ways to discover his purposes and the way we should live them out. Lent, with the increased self-knowledge it can bring, can be a time of growth. In these talks, present-day voices offer new insights into profound new ideas. They signpost ways to recognize the pitfalls ahead. They give permission for us to accept that some things are hard and demand perseverance. Even in the face of failure, they tell us, there is new wisdom to be found that may be ultimately more far-reaching. And success may take shapes it is hard for us to recognize at the outset. The words of these Lent talks offer a kind of nourishment. This book is a feast for the contemporary soul.

Christine Morgan

Head of Radio, BBC Religion and Ethics

WHETHER WE APPRECIATE THE STORY OF THE PASSION AS DIVINE REVELATION OR SIMPLY AS POETRY OR METAPHOR IT IS THE ARCHETYPAL PRESENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE MYSTERY DRAMA: THE MYSTERY OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE ALIVE.

First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 25 February 2015

James Runcie is a writer, director and literary curator. He is the author of the series The Grantchester Mysteries, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, Visiting Professor at Bath Spa University and the Commissioning Editor for Arts at BBC Radio 4. He was a founder member of The Late Show and made documentary films for the BBC for 15 years. He then went freelance to make programmes for Channel 4 and ITV. He was Artistic Director of the Bath Literature Festival from 2010 to 2013 and Head of Literature at the Southbank Centre in London from 2013 to 2015.

Back in 2010 I started to write a series of detective novels with the provisional title The Grantchester Mysteries. The stories begin in an English village in 1953 when the death penalty was still extant, homosexuality was illegal and human relationships were probably conducted in a more private manner than they are in our contemporary world of relentless self-disclosure.

What I wanted to do was tell a tale of post-war Britain using the mystery story as a framework. It was to be an account of social and ethical change with murder, theft, betrayal and injustice.

Crime writing is helpful for this. It gives the author the opportunity to put characters under extreme pressure and see how they react to the continual threat of death and disaster.

The precariousness of the human condition, the awareness of time and mortality, and the ability to react to abrupt shifts in fortune, whether good or bad, are paramount. They would be morality tales, parables even, aiming for the economy of storytelling found in the Bible; meditations on the sin and suffering that underpin religious thinking, particularly in Lent.

When I began to plan the stories I realized that the central character could easily have been a doctor or a teacher, but I chose a priest. I wanted someone with easy access to personal secrets; present at key moments of birth, marriage and death; someone who also had sufficient freedom of movement to go where the police could not.

I also wanted religion to be taken seriously as a subject. I hoped to escape the sitcom clichs of All Gas and Gaiters and Bless Me, Father and to have, as the main character, a questioning, thoughtful Church of England vicar rather than the kind once played by Derek Nimmo, Dick Emery or Rowan Atkinson, the latter in Four Weddings and a Funeral . That didnt mean comedy would not have its place, but it would be a world in which the comic and the tragic, the profound and the trivial could exist side by side. This genre of writing is often belittled as cosy crime historically these are stories in which one doesnt need to worry too much about the graphic depiction of the violence found in hard-boiled alternatives and, indeed, in the Bible. Cosy crime is not a term I like very much. One has to remember that under the cosy, the pot may be scalding and the tea poisoned. Violence, and the consequences of crime, cannot be ignored so easily.

Next page