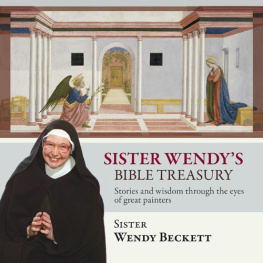

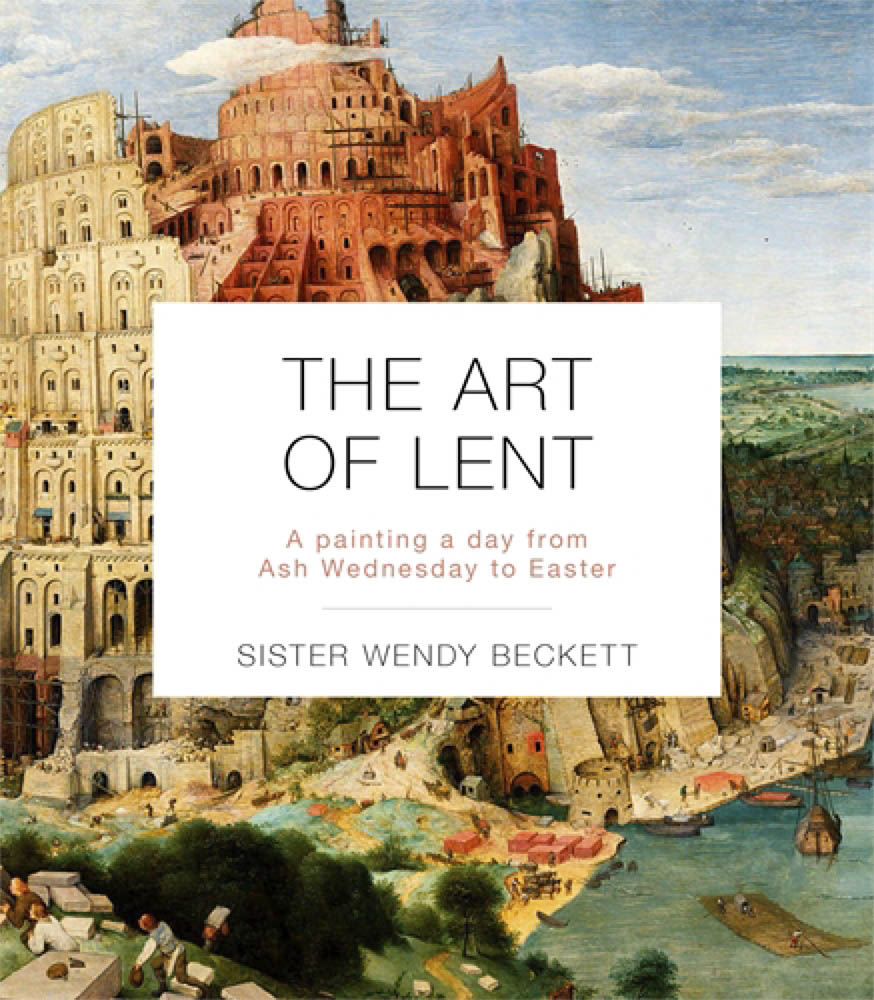

Sister Wendy Beckett went straight from school to the novitiate of an active teaching order, which sent her to Oxford and then engaged her in its schools and at a university. Her longing to spend her time in prayer was finally answered when she was 40 and she was allowed to lead a contemplative life under the protection of the Carmelites. She has spent her time in prayer ever since, which includes making programmes on art for the BBC and writing books on art, on icons and on prayer. Now, nearing the end of her life, she is a deeply content and grateful woman.

The Art of Lent

A painting a day from Ash Wednesday to Easter

Sister Wendy Beckett

The Art of Lent

The Great Wave , 1831, Katsushika Hokusai

We cannot control our life. As Hokusai shows so memorably, the great wave is in waiting for any boat. It is unpredictable, as uncontrollable now as it was at the dawn of time. Will the slender boats survive or will they be overwhelmed? The risk is a human constant; it has to be accepted and laid aside. What we can do, we do. Beyond that, we endure, our endurance framed by a sense of what matters and what does not. The worst is not that we may be overwhelmed by disaster, but to fail to live by principle. Yet we are fallible, and so the real worst is to forget our fallibility, to refuse to recognize failure and humbly begin again.

Ash Wednesday reminds us of our constant need to acknowledge and confess our fallen humanity, to repent of the past and throw ourselves on the loving mercy of God. For we have been assured that nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (Romans 8.3839).

The Return of the Prodigal Son , c. 166169, Rembrandt van Rijn

If we had nothing of Jesus teaching, except this one parable, we would still understand his message of love. It is his supreme example of the immensity, almost the folly, of Gods love for us. Rembrandt, most tender of painters, is sensitive to every nuance of the prodigals return. This is the bad son, the wilful spendthrift, who cared nothing for his father or his adult responsibilities while the money lasted. It is only when he is starving and homeless that he returns home. Rembrandt shows him in his ragged humiliation. It is not just that his father receives him back with such compassion: it is the fathers eagerness that astonishes us. He is watching out always for this lost child, abundantly ready to lavish upon him the good clothes, the feasting and cherishing, that have been so wilfully disregarded. The other son (is that him on the right?), the good, prim, self-righteous son, cannot understand the fathers attitude. Perhaps we cannot understand it either, but this is what it means to love and forgive.

Self-portrait with Dr Arrieta , 1820, Francisco de Goya

As the holiest among us know (in fact especially the holiest), we are a sick and sinful people. We all fall short of the glory of God and none of us, to our grief, can say, I do always the things that please him. In this wonderful self-portrait the ageing Goya looks without illusion at his state of sickness. It is this clear, hard, realistic look at ourselves that we all need. But Goya also shows that he is not alone. His beloved doctor friend is with him, comforting him, healing him, in fact saving him. Skilful though Doctor Arrieta was, his very look of anxiety reveals that he knows that he is not all-powerful. But our doctor, our Saviour, is all powerful. As our Lord himself said, Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick; I have come to call not the righteous but sinners (Mark 2.17).

The Harvest is the End of the World and the Reapers are Angels , 1989, Roger Wagner

The essential sign that we have grown up is that we can accept responsibility. All actions have consequences, but the consequences may not be visible. Jesus is adamant that he will not destroy the wheat and the tares, that he will let the sheep and the goats pasture together until the time of judgement. None of us is wholly wheat or wholly tare: we are a mixture of both. But every tare we have sown must be destroyed so that we can be pure wheat for Gods holy bread. Either we must wait until the time of judgement for the angels to reap Gods harvest or we must cooperate with him and do it while we are still alive. Wagners picture, with a dark, threatening sky and the angels with their sickles, forewarns us of what is to come. We may look over our lives and see a vista like the golden grain, but God knows there are tares hidden there. He will destroy them if we truly desire him to make us pure.

First Sunday in Lent

For God alone my soul waits in silence.

PSALM 62.1

Woman with a Pink , 166569, Rembrandt van Rijn

The capacity for silence a deep, creative awareness of ones inner truth is what distinguishes us as human. All of us, however ordinary or flawed, have at heart a seemingly boundless longing for fulfilment, and it is their consciousness of this that makes Rembrandts portraits so beautiful. The Woman with a Pink is lost in the depths of her private reflections. Her dark background is symbolically unimportant, lending greater expression to the soft brightness that plays upon her face. Visibly silent, she is explicitly encountering the mystery of being human. She does not contemplate the carnation (the pink), usually an emblem of love, but looks within, in silence, quiet and engrossed.

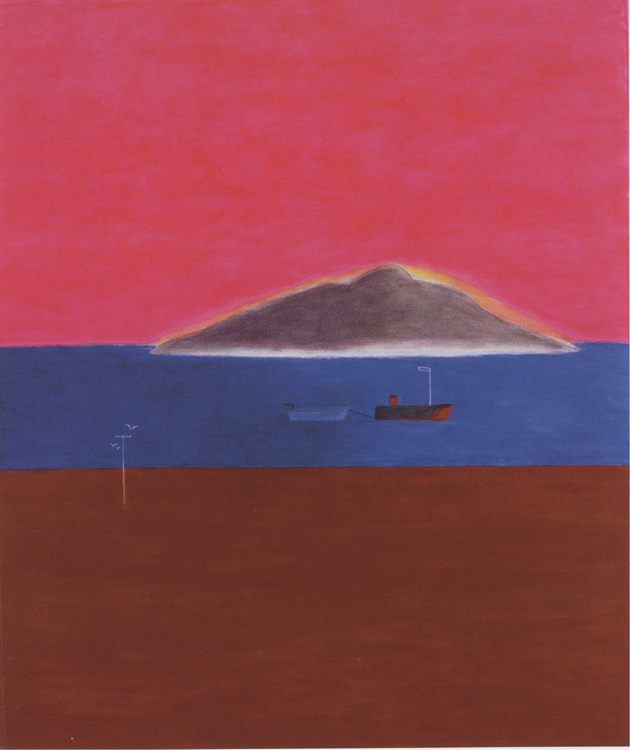

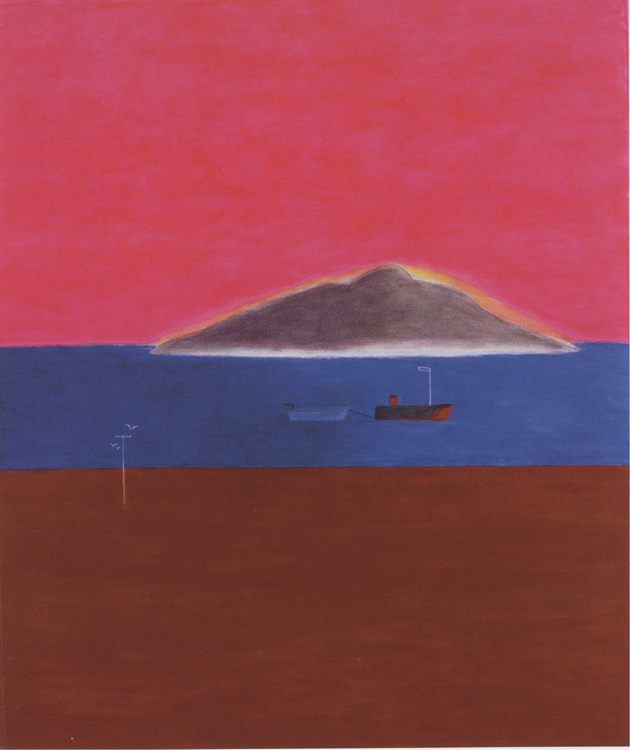

Holy Island from Lamlash , 1994, Craigie Aitchison

Profound silence is not something we fall into casually. This may indeed happen, and a blessed happening it is, but normally we choose to set aside a time and a place to enter into spiritual quietness. (Those who never do this, or shrink from it, run a very grave risk of remaining half-fulfilled as humans.) Craigie Aitchisons view of Holy Island pares this choice down to its fundamental simplicities. Brown earth, blue sea, red sky, Holy Island a stony grey lit by glory. There is a small ship to take us across, if we choose to ride in it. There are no fudging elements here: all is clear-cut. This is not silence itself but rather the desire for silence. Silence, being greater than the human psyche, cannot be compressed within our intellectual categories; it will always escape us. But the desire to be silent, the understanding of the absolute need for it: this is expressed in Aitchisons wonderful diagram of life within the sight of the holy.

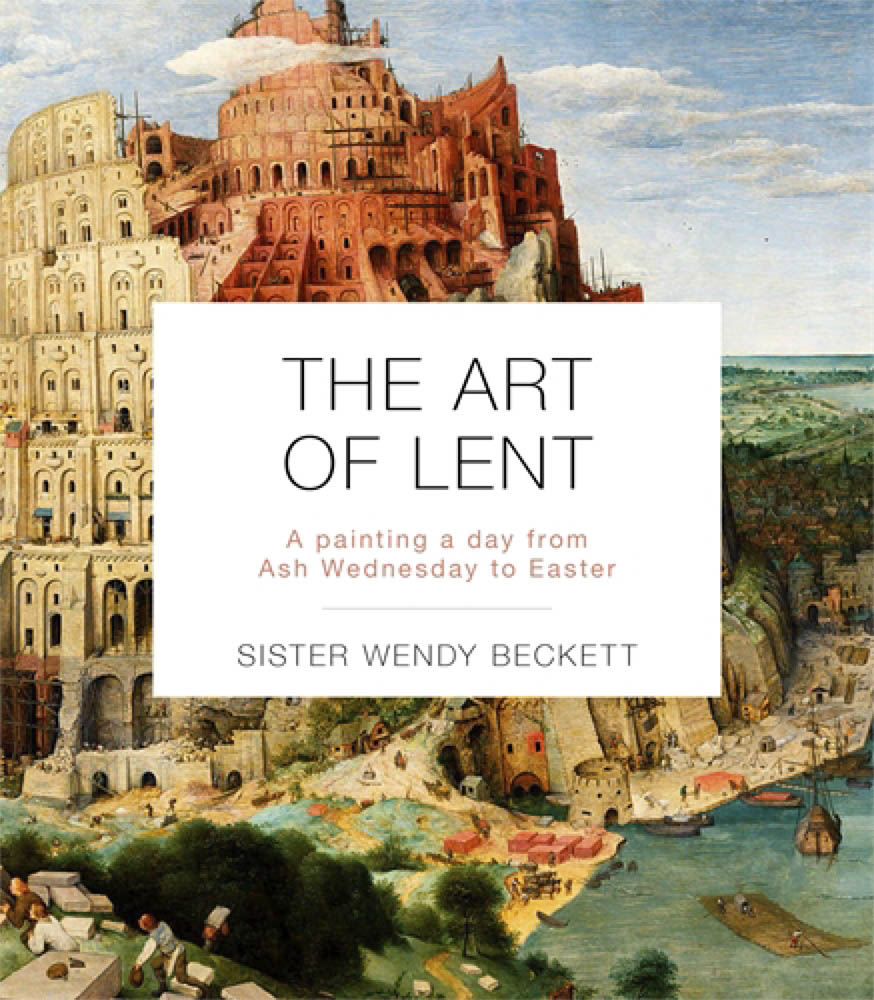

The Tower of Babel , c .1563, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

What silence principally armours us against is Babel: the endless foolish chatter, words used to confound thought, words misused to ward off friendship or attachments, words as occupation. The biblical Babel was a metaphor for the loss of human ability to communicate as a consequence of the rise of different languages; but the foreignness of other tongues is a smokescreen. To express what one means, and to hear what another means: this is a rare thing. Babel is profoundly destructive of our energies, as Bruegel so splendidly shows. This monstrous tower is consuming all who labour on or near it. We have an absolute need for quiet, for the hearts wordless resting on God.

Next page