Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books hardback original 2022

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Repeater Books 2022

ISBN: 9781914420023

Ebook ISBN: 9781914420030

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

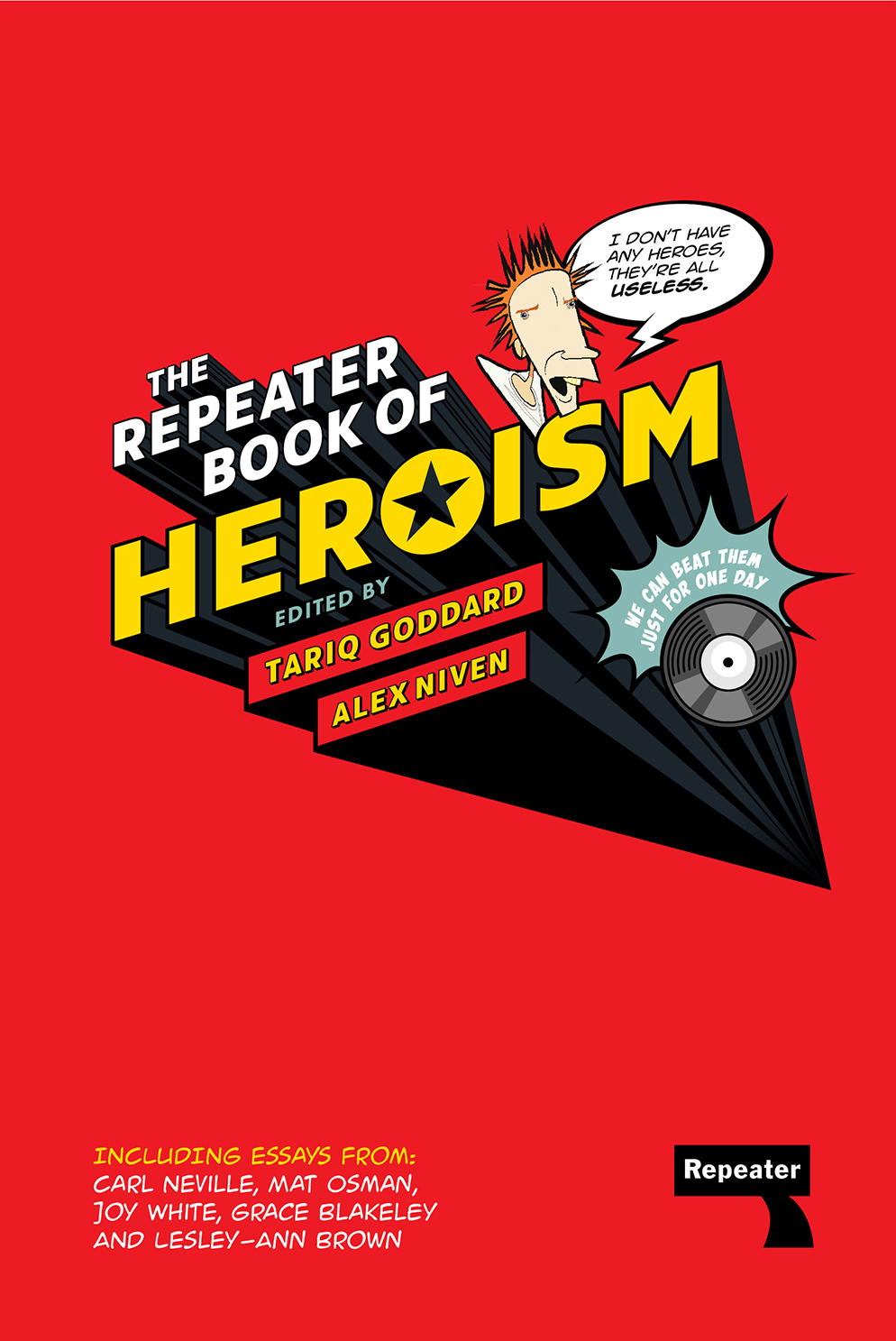

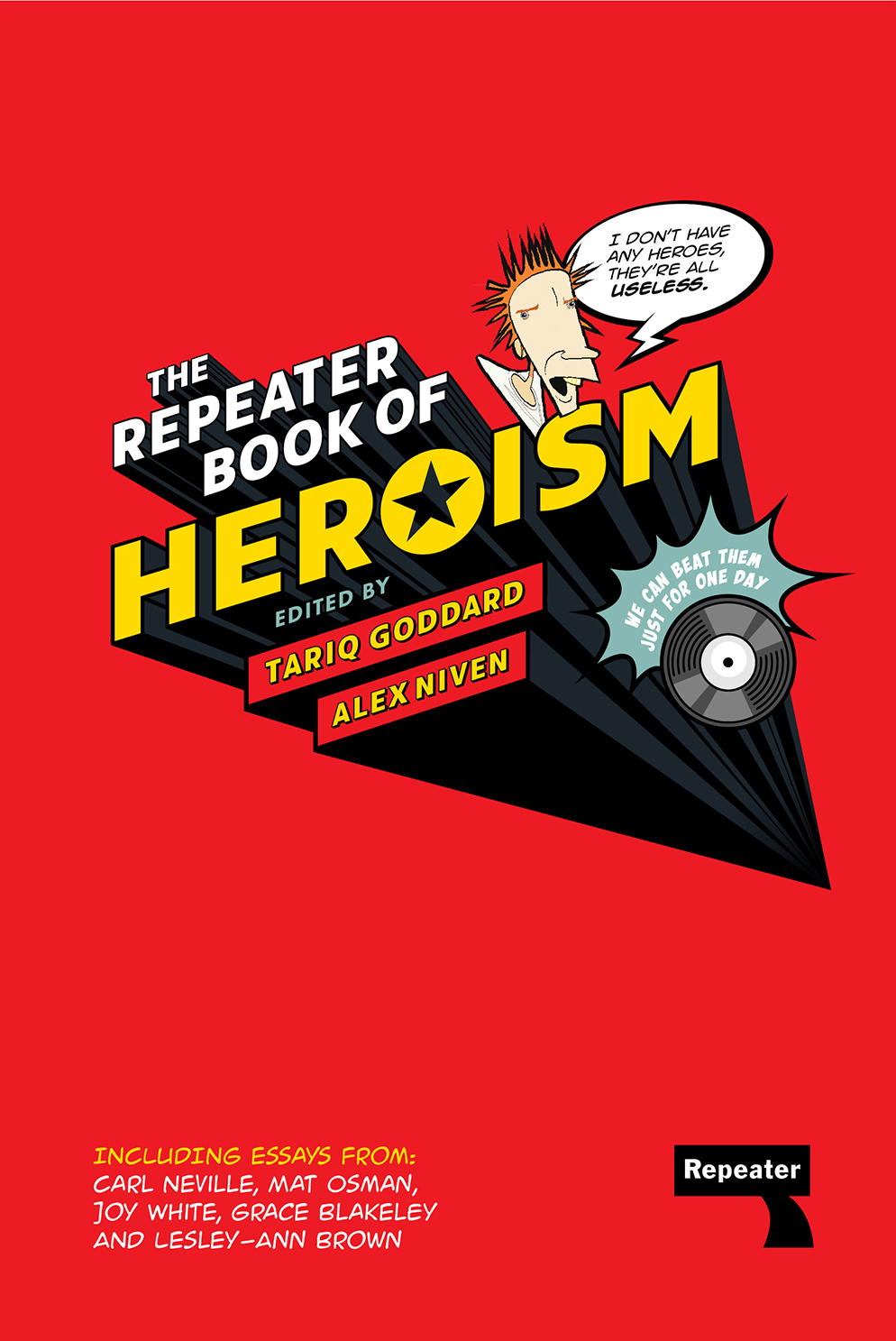

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd

To be on the left, one requires possession of a quixotic sense of romanticism. From the Paris Commune to the Spanish Civil War, Che, the Black Panthers and striking workers we have always been inspired by sacrificial heroes. The old macho idea of great men of history and the millenarian fashion for non-hierarchal horizontalism killed off the need for such figures. Sorry, its a fact that in the twenty-first century we are in need of new charismatic leaders, heroes even. This book is an unashamed celebration of the everyday heroic. Read and be inspired.

B OBBY G ILLESPIE

For Dawn Foster, Repeater hero number 1

CONTENTS

TARIQ GODDARD & ALEX NIVEN

ALEX NIVEN

PETER FLEMING

JOY WHITE

CARL NEVILLE

RYANN DONNELLY

MAT OSMAN

GRAHAM HARMAN

CHRISTIANA SPENS

MARCUS BARNETT

PATRICK A. HOWELL & CHRISTIAN W. HOWELL

JOE KENNEDY

MATTEO MANDARINI

OWEN HATHERLEY

LESLEY-ANN BROWN

GRACE BLAKELEY

ANDY SHARP

TARIQ GODDARD

INTRODUCTION / TARIQ GODDARD & ALEX NIVEN

For the longest time, heroes and heroism have had a bad press. For a host of reasons World War II perhaps, or postmodernism, or punk the ancient art of glorifying a single human being has, for at least half a century, been one of the biggest taboos in almost every discourse going. Putting someone up on a pedestal has become something you definitely do not do under any circumstances the suggestion itself synonymous with a proscribed desire to rate, categorise and rank.

In practice, of course, this new decorum has arisen at the same time as inequality between individuals has notably failed to disappear. Meanwhile, a new kind of mythic figure has thrived as never before. In the bleak dreamscape of twenty-first-century capitalism, icons, influencers and curators are perfectly acceptable. Similarly, celebrities and celebrity culture (in sport, art, fashion and politics) are part of the lifeblood of an increasingly depraved system. Quasi-authoritarian leaders like Trump, Orbn, Modi and Bolsonaro (and, lower down the food chain, desperate end-of-the-pier turns like Johnson and Farage) have dominated later neoliberalism, for all their bogus claims about being figureheads of a popular backlash against the status quo.

In this context, is there any room at all for the old-fangled, moth-eaten figure of the hero or at least the related, but not necessarily insuperable concept of heroism?

The deeper reasons for the contemporary lefts misgivings about heroism are historically understandable. An outlook that prizes equality and distrusts meritocracy might wonder what it has to learn from heroism per se. Yet such scepticism is as much a symptom of political defeat as it is sound egalitarian sense. Fifty years ago, the entries in a collection like this would have chosen themselves: Marx, Engels, Trotsky and Mao, or perhaps Cleaver, Castro, Guevara and possibly even Baader, a verifiable rollcall of revolutionary virility. The belief that a radical leader should want to overthrow society and establish a new order (an idea most prevalent in the campuses of the North Atlantic democracies), held enormous aesthetic and social, if not always political, traction.

However, the political failure of authoritarian socialism, the emphasis on human rights and turn against violence as an effective way of achieving ones political goals felled this article of faith and broke the pantheon apart, discrediting some of its luminaries and rendering others, at best, irrelevant. A new consensus saw all leaders, even good ones, as necessarily having blood on their hands, and heroism itself as a destructive stance, more likely to encourage macho posturing than creative invention. By abandoning armed revolution, the dictatorship of the proletariat and a vanguardist leadership, the left junked those features most closely associated with them individual personality cults, elitism and exceptionalism in general all of which have become the province of the right.

Having lost the external signifiers of heroism, the next step was to deprive it of its driving forces inspiration and appeals to raw feeling, which as essentialist enablers, theological anachronisms or bourgeois constructs, were now as toxic as bravery, courage, sacrifice and fortitude. Instead of these hoary old platitudes, new and ever more exacting standards of perfect(ly moral) behaviour were required for a person to be worthy of unordinary admiration. In its most extreme form, this variety of resentment used criteria the progressive left would traditionally have avoided: that a person should be judged by the worst thing they have ever done and not the best, that ontological redemption, the ability to create something good or of utility even when otherwise morally compromised, was a form of cheating and therefore worthy of disqualification. Against such odds, heroism could not possibly survive, and its replacements, however noble, worthy or deconstructive, were simply not heroic enough to fulfil its old functions.

The essays in this book are all in some way based on the premise that a hero is, in spite of everything, something to be. To be clear, in wishing to make the case for the legitimacy of heroism as an idea and rallying cry in the twenty-first century, we are not trying to resuscitate reactionary, outdated and discredited forms of hero-worship. In 1841, at the start of the Victorian era, the Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle published On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History . Carlyles book was in the main a sinister development, which kick-started a modern tradition of dealing with heroes and the heroic that would lead to some very dark places indeed. In making a passionate case for a Great Man theory of human history, On Heroes opened the door to all manner of ethical evils, from the notion of male greatness to the forms of imperialist and authoritarian domination which follow from a belief that, as Carlyle put it: great men are the commissioned guides of mankind, who rule their fellows. It is no wonder that the concept of an all-powerful bermensch was later developed and adopted by twentieth-century fascist ideologues, who took Carlyles argument as their food and drink.

Next page