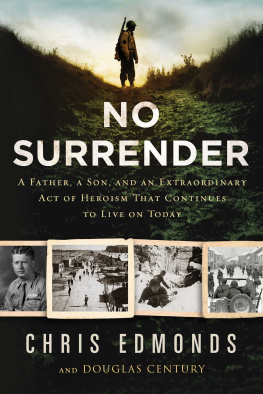

Three hours before dawn on Thanksgiving Day 2005, I startled from a peaceful sleep. I was sweating, murmuring the words of my late father, Roddie, which flooded my mind with confusion. I had been dreaming about his World War II journals, neatly written in pencil script. No one can realize the horrors the infantry soldier goes through, he wrote. You get scared and I mean scared. Dont let anyone tell you that he wasnt scared.

Those words surprised me. I had never seen my dad afraid of anything. He was fearless; he had a quiet faith in God that made him seem invincible. Dad always marched to the beat of faith, hope, and love. But never fear. Not once in all the years I knew him.

What could have happened to make Dad so afraid?

My dad had served in the infantry in Europe during World War II. He hit the beaches of France several months after the initial D-Day landings, slogged through freezing rain and mud in the fall of 1944, and fought in the icy forests of Belgium during the brutal Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive on the Western Front. He spent the final months of the war as a POWa prisoner of warin Ziegenhain, a tiny town in central Germany.

I didnt know much more about Dads service during World War II. Like a lot of members of the Greatest Generation, he never discussed the grisly details of the war. Almost everything I knew I had learned from history books.

Now wide awake, I sat up in bed thinking about Dad. It was a chilly morning in Maryville, Tennessee. The temperature was slightly below freezing. I looked at my wife, Regina, who was still asleep beside me, just as she had been every night for the past twenty-eight years. I pulled the comforter over her shoulder to protect her against the chill.

I went to the bathroom and splashed cold water on my face. I stared into the mirror and asked myself: Why didnt I ask Dad more questions about the war before he died?

I had been thinking about my fathers wartime experiences since the previous evening. Just after dinner, my daughter Lauren had arrived home from Maryville College, where she and her identical twin sister, Kristen, were earning their degrees in education. Lauren was excited to tell us about her new history project; her group was to prepare an oral history of a family member who had led a noteworthy life.

Dad, when I told my group that Papaw was a POW in World War II, they said he was definitely the story, even though hes no longer alive, Lauren said. What do you think?

I told Lauren that I thought it was a great idea. If I were you, Id begin with his wartime journals, I said. Nana has them tucked away somewhere in her house. I told her I had read them several times, but her papaw never talked about the war.

Not even to Nana?

No, not even to Nana.

Later, I thought about Laurens newfound excitement about her grandfather. Lauren was born in 1985, six months before her papaw Roddie died. She didnt know much about him.

Two peas in a pod, Dad had said when the twins were born. I cant tell em apart. And theyre joining our third lil pea, big sister, Alicia Marie.

My three girls were inseparable as they grew up in the 80s and 90s. They excelled at school, played house, and collected Barbies. When they were a bit older, they became athletes, taking up cheerleading, gymnastics, softball, basketball, and volleyball. On Friday nights they gathered to watch sitcoms. Papaw Roddie was right: They were three peas in a pod.

Dad had always seemed to be right about people. He had an uncanny ability to read a persons heart and see their true character. This served him well all his life. On weekends, Dad used to visit homeless shelters, churches, nursing homes, and veterans groups in Knoxville, offering encouragement to people in danger of losing hope. He did this simply because he thought it was the right thing to do.

I wanted to help Lauren learn about her papaw and his experiences during World War II, but I knew only the broad strokes of Dads wartime experiences. I knew he had served as a master sergeant in the US Army. I knew he had fought with the 422nd Regiment of the 106th Infantry Divisionthe Golden Lions. I knew he had been a prisoner of war, captured sometime during the Battle of the Bulge. But thats all I knew. I was ashamed I didnt know more, that I hadnt asked him more questions when I had the chance. I wished my girls had known my dad.

I had been in my midtwenties, an unemployed father of three, when Dad passed away at the age of sixty-five. He died from congestive heart failure at his Knoxville home on August 8, 1985, twelve days before his sixty-sixth birthday. He chose to die at home, on his own terms. When he learned that he was sick, he checked himself out of the hospital, determined to enjoy his last few months at home.

I dont know how long I had been lost in thought that night as I stood in the kitchen when Regina came to me and asked me what was wrong.

I feel like Im letting Laurenand her sistersdown, I said. I should know more about Dads experiences in the war, but I dont. Had I not cared enough to ask him? I didnt know much about his childhood during the Depression or what he was like in high school either. It was like Dad lived an entire lifetime before I was born.

Regina, who had always loved my dad, listened, then reminded me that he never really talked about his past. He just lived in the present. That was Roddie. He was a wonderful dad and a wonderful person. A terrific grandfather too.

I thought about what I had read in my fathers journal: If a man lives through a major engagement, he isnt much good after that.

That didnt make sense. My father was good after that. I dont know all that he went through over there, but he didnt seem to have had any aftereffects from the war, I said to Regina.

My father was always optimistic, always upbeat. He used to tell me, Son, life may knock you down, but you can always fly high as a kite. He wouldnt let things keep him down. He inspired me with his positive outlook. He never quit.

It sounds corny, but Dad was always my hero. Not because hed survived the Depression and was a member of the Greatest Generation. Not because he served as an infantryman who fought in Europe to save the world from fascism. Not because he stayed in the Army National Guard, and five years laterat the age of thirtyfound himself on the front lines again, this time in Korea.

No, Dad was a hero because he was there for me in the ordinary ways. He coached my Little League team, teaching me and my buddies how to lay down a perfect bunt, how to read the opposing pitchers windup, and how to know when it was safe to steal second base.

He was sincere in his faith too. His love for God and other people was infectious, a model for living that I still try to follow. Dad cared about everyone he met; it didnt matter who they were. He always closed our family prayers with a simple request: Lord, help us help others who cant help themselves.

Dad was smart, although he never attended college. I never asked why he didnt take advantage of the GI Bill, which would have paid for his education after the war. He was well-read, artistic, and witty, loved wordplay, and was masterful with crossword puzzles.