SCOTTCHAN/Shutterstock, Inc.

SCOTTCHAN/Shutterstock, Inc.

Alamy Images

T HREE HOURS BEFORE DAWN on Thanksgiving Day 2005, I startled from a peaceful sleep. I was sweating, murmuring the words of my late father, Roddie. I had been dreaming about his war journals, neatly written words, jotted in pencil, in his own cursive hand. No one can realize the horrors the Infantry soldier goes through, he wrote. You get scared and I mean scared, and dont let anyone tell you that he wasnt scared.

Dad never seemed scared of anything. When he was alive, he was always fearless, with the kind of quiet Christian faith that made him seem invincible. He always marched to the beat of faith, hope, and love. But never fear. Not once in all the years I knew him.

Lying awake, staring up at the dark ceiling, my mind flooded with confusion, and I whispered Dads favorite Bible passage, Romans 8:3739.

Yet in all these things we are more than conquerors through Him who loved us. For I am persuaded that neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.

What could have happened over there to make Dad, armed with such strength, so afraid?

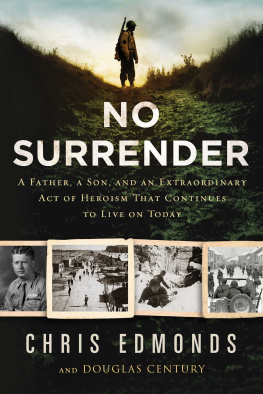

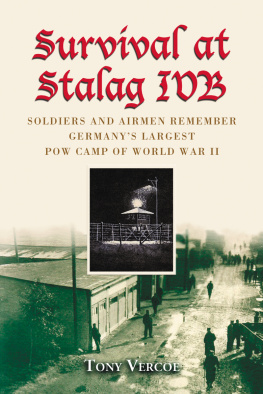

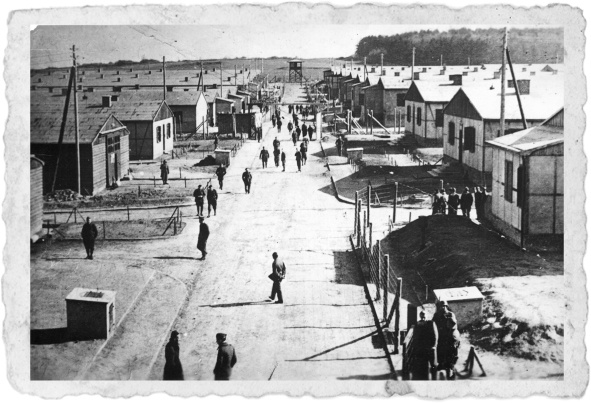

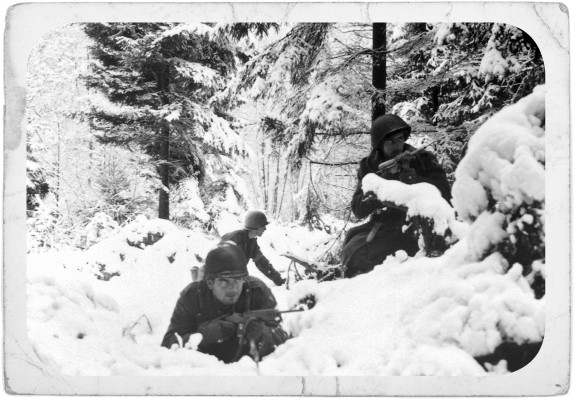

For Dad, over there meant Europe during the Second World War. It meant Ziegenhain, an obscure town in the Rhineland-Palatinate of Germany, where he spent the final months of Nazi tyranny. He hit the beaches of France several months after the initial D-Day landings, slogged through freezing rain and mud in the fall of 1944, and saw horrific combat in the icy forests of Belgium that final brutal winter of the war, fighting along the supposedly impenetrable Nazi Siegfried Line in the Battle of the Bulge.

I knew little about Dads service during World War II. Like a lot of members of the Greatest Generation, he never discussed the grisly detailsI had only read about them in history books: dark skies exploding with relentless mortar fire; officers and infantrymen, already frozen in the winter cold, stunned by the ferocity of the barrage, a thunderous assault of 88 mm artillery fire followed by wave after wave of panzers and Nazi troops.

Now wide-awake, I sat on the edge of my bed for a few moments. It was a chilly morning in Maryville, Tennesseethe sun hadnt come up yet. I checked my cell phone. The temperature was slightly below freezing. I looked at my wife, Regina, who was still asleep beside me, just as she had slept every night for the past twenty-eight years. I pulled the comforter over her shoulder to protect her against the chill.

I rose from bed, stunned and confused by Dads wartime confession, and stole away to the bathroom, where the sense of regret overwhelmed me. I splashed ice-cold water on my face to calm myself. Staring into the mirror, I saw a reflection of brokenness, the sound of my fathers voice still ringing in my head.

Why didnt I ask Dad more questions before he died? Why did I let him take it to his grave?

I had been thinking about my fathers wartime experiences the previous evening. Just after dinner, as I had helped Regina clear the table, our daughter Lauren had arrived home from Maryville College, where she and her identical twin, Kristen, were earning their degrees in education. Lauren was excited to tell us about a new history project: to interview a family member about a notable experience in their lifeideally an oral history of that person.

Dad, when I told my group that Papaw was a POW in World War II, they said he was definitely the story, even though hes no longer alive. What do you think?

I told Lauren I thought it was a great idea. If I were you, Id begin with his wartime diaries. Nana has them tucked away somewhere in her house.

Thats amazing, Lauren said. Have you seen them?

I haveIve read them several times, I said. You know, its hard to imagine, but Dad never talked about them.

Not even to Nana?

No, not even to Nana.

Later, while I was cleaning up after dinner with Regina, I stopped wiping down the countertop to reflect on Laurens new excitement about her papaw Roddie. She was born in 1985, six months before he died. She knew little about him. But it seemed Dad had known her and Kristen instantly. Two peas in a pod, he had said when they were born. Cant tell em apart. And theyre joining our third lil pea, big sister, Alicia Marie.

Inseparable, they were typical sisters, my three girls, growing up in the 80s and 90s. They excelled at school, played house, had every Barbie and accessory created, loved Teddy Ruxpin, were cheerleaders, took gymnastics, and played softball, basketball, and volleyball. Friday nights they gathered to watch Family Matters, Step by Step, Boy Meets World, and Full House. Alicia, a future cosmetologist, loved to fix their hair, nails, and makeup, even if it was pretend. Papaw Roddie was rightthey were three peas in a pod.

Dad had always seemed to be right about people. Everyone acknowledged he had an uncanny ability to read a persons heart and instinctively see their true character. It wasnt judgmentmore understanding, empathy, and helpfulness. This had served him well all his life. He used to spend his weekends visiting homeless shelters, churches, nursing homes, and VA groups in Knoxville just to sing and to encourage people in danger of losing hopeoffering up his time, in service, simply because it was the right thing to do.

I wished my girls had known him. And Lauren deserved to learn as much as she could about her grandfatherespecially his experiences during World War II. Of course, I knew the broad strokes of Dads wartime experiences. I knew he had served as a master sergeant in the US Army. I knew he had fought with the 422nd Regiment of the 106th Infantry Divisionthe Golden Lions. I knew he had been a prisoner of war captured sometime during the Battle of the Bulge. But thats all I knewnot much, to be perfectly honest. And I was ashamed I didnt know more, that I hadnt asked him more questions when I had the chance.

I was in my mid-twenties, an unemployed father of three, when Dad passed away at the age of sixty-five. He died from congestive heart failure at his Knoxville home on Drifting Drive on August 8, 1985, twelve days from his sixty-sixth birthday. Dying at home on his own terms had been Dads choiceit was his decision. Faith, family, friends, freedomthats how he lived. And thats how he died too. Determined to enjoy his last few months at home, he had checked himself out of the hospital.

As I stood in the kitchen, I must have been a thousand miles away, lost in my own thoughts. Regina put her hand on my shoulder and asked me what was wrong.