Katharina Stegelmann

Staying Human

The Story of a Quiet WWII Hero

Translated by Rachel Hildebrandt

Skyhorse Publishing

To my husband, Henning

Copyright 2014 by Katharina Stegelmann

Katharina Stegelmann: BLEIB IMMER EIN MENSCH. Heinz Drossel.

Ein Stiller Held 19162008.

Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 2013

First Skyhorse edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo credit from private source

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-553-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-135-5

Printed in the United States of America

Foreword

I met Heinz Drossel on a hot August day in 2003. He had already agreed to give me an interview that would serve as the basis for a biographical article about him as a quiet hero for the Spiegel publication, Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit (The Presence of the Past). Soon afterward, I decided that I wanted to tell the story of this man and his family in more detail than I had been able to at that time. Heinz Drossel immediately agreed when I asked him if he would allow me to write the history of his family. We met numerous times, telephoned regularly, and exchanged countless emails. We traveled together so that he could introduce me to his daughters, grandchildren, and acquaintances. We became friends.

I wrote the history of Heinz Drossel and his wife Marianne after many conversations with him, readings of his memoirs Die Zeit der Fchse (The Time of the Foxes), analysis of the legal records related to the reparations proceedings connected with Marianne Drossel, and conversations with the family members and friends who are still alive today. I also pursued research in various institutions and archives. I have pulled the facts together in order to present a truthful depiction of the events. However, the truth cannot be found in this book. At least, not the full truth.

The memories of those still alive and the statements of family members about the now deceased protagonists did not produce a unified picture. There were contradictory, illogical pieces of information. Holes remained, and some things could not be clarified through research. I had to stay silent on some things because those involved wished this. I have made some deductions, choosing the most likely variation and occasionally risking enhancement, in order to create a picture of how it could have been.

Do It Better!

Osterholz-Scharmbeck, near Bremen, May 24, 2004

I t is pretty close quarters in the high school music room. Almost 150 teenagers, students from all five tenth-grade classes, are present. The guest sits behind a desk with a glass of water to his right, a microphone to his left, and a few pieces of paper in front of him. He is slight and gray-haired. He wears no glasses. He is old. As he stands up from his chair, his movements are hesitatingly uncertain, as if he has balance problems. Then he pulls himself together and suddenly seems somewhat younger. He crosses to the edge of the little stage. The general noise is disrupted by shh and quiet. The small, old man looks quietly out across his audience. He pulls his shoulders back a little and says: Good morning. It is now quiet.

I was born in the old German empire, relates Heinz Drossel. For the students, this is fascinating. It is as if all 150 teenagers are briefly holding their breath. In the empire! The man up there on the podium is truly ancient.

I was born in the old German empire. I experienced the collapse after World War I, and I very consciously experienced the Weimar Republic. With effort, I survived Adolf Hitlers thousand-year Reich and his horrendous war. And since that time, I have lived in the Federal Republic of Germany.

The teenagers who do not have their regular lessons on this sunny May day are about 16 years old.

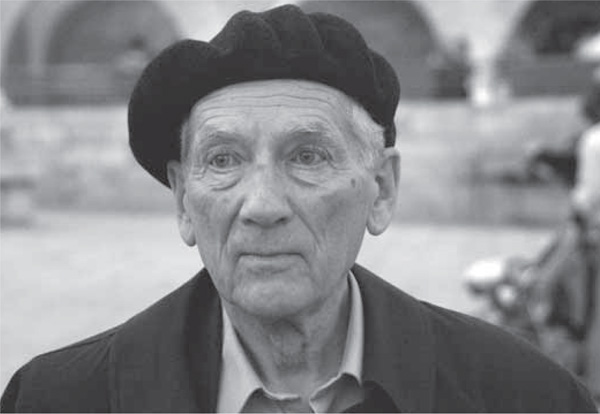

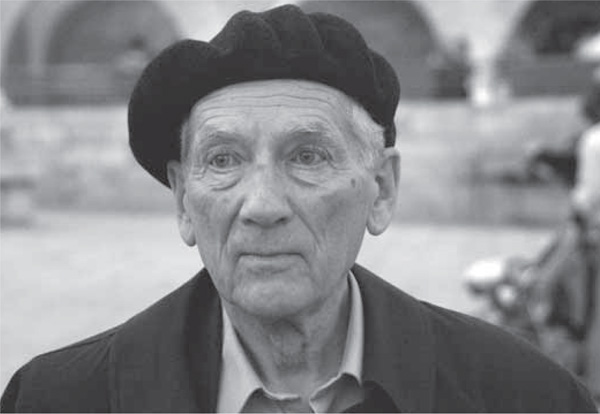

Heinz Drossel, 2005 in Jerusalem

They are here to listen to a contemporary witness. On the teaching plan for today, the words National Socialism are written. Drossel might well be the first person that these young people have ever met in person who experienced this dark period in Germanys history as an adult. Certainly, some of them might have grandparents who were adults in the so-called Third Reich, perhaps even a grandfather who lost his life as a child soldier. However, these young people are now hearing a firsthand account of what it was like to live under the Hitler dictatorship, what it meant to live through this, what it was like for the parents of an acquaintance to suddenly disappear, or what one felt as a 16-year-old when a friend was no longer permitted in a caf because he was Jewish.

Heinz Drossel lifts up several worn-out notebooks. As he explains, these were his war diaries. They are over 60 years old and were with him in France and in Russia. At the conclusion of his talk, the students, whom he formally calls dear friends, are welcome to come up and look at the little books.

Walking back and forth across the small stage and imitating a Gestapo officer, Drossel tells the story of how he went to this officer as an 18-year-old to ask about one of his fathers business partners who was missing. He reports how he wanted to have a farewell cup of coffee with his friend Salomon, and how a Nazi loudly demanded, The Jew must get out! Drossels voice becomes quiet, as he looks sadly across the audience: I was ashamed to be a German then.

Drossel talks about his role models, his father and his grandfather, and how both of them encouraged him to explore and analyze the world. He returns to the confusion of the Weimar period. As a schoolboy, he was sent out to buy bread in the morning for his family; this minor purchase was acquired with million-mark bills. And he talks about how he saw the Orthodox Jews from the East, who lived in the Scheunen Quarter in Berlin.

Drossel only spends a little time describing his experiences as a soldier and an officer on the front. Soldier stories are not emphasized. Even in this phase of his life, he had his own ideas, and he tried to remain true to his convictions. It is obvious that, above all, humanity is of the greatest value to him. And that he did not seek to avoid any discomfort or risk when he recognized that this value was in danger. How else could he have decided in a seconds time to organize a hiding place for four Jews in January 1945 in order to enable them to escape from the Gestapo? One of the rescued Jews, Ernest Frontheim, became his best friend. According to Drossel, a meeting with his grown daughter years later revealed to him the true significance of what he had done: As I held her in my arms, I was suddenly aware that this woman probably never would have existed, if I had done things differently.

Next page