Inflamed Invisible

Sonics Series

Atau Tanaka, editor

Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance, Brandon LaBelle

Meta Gesture Music: Embodied Interaction, New Instruments and Sonic Experience, Various Artists (CD and online)

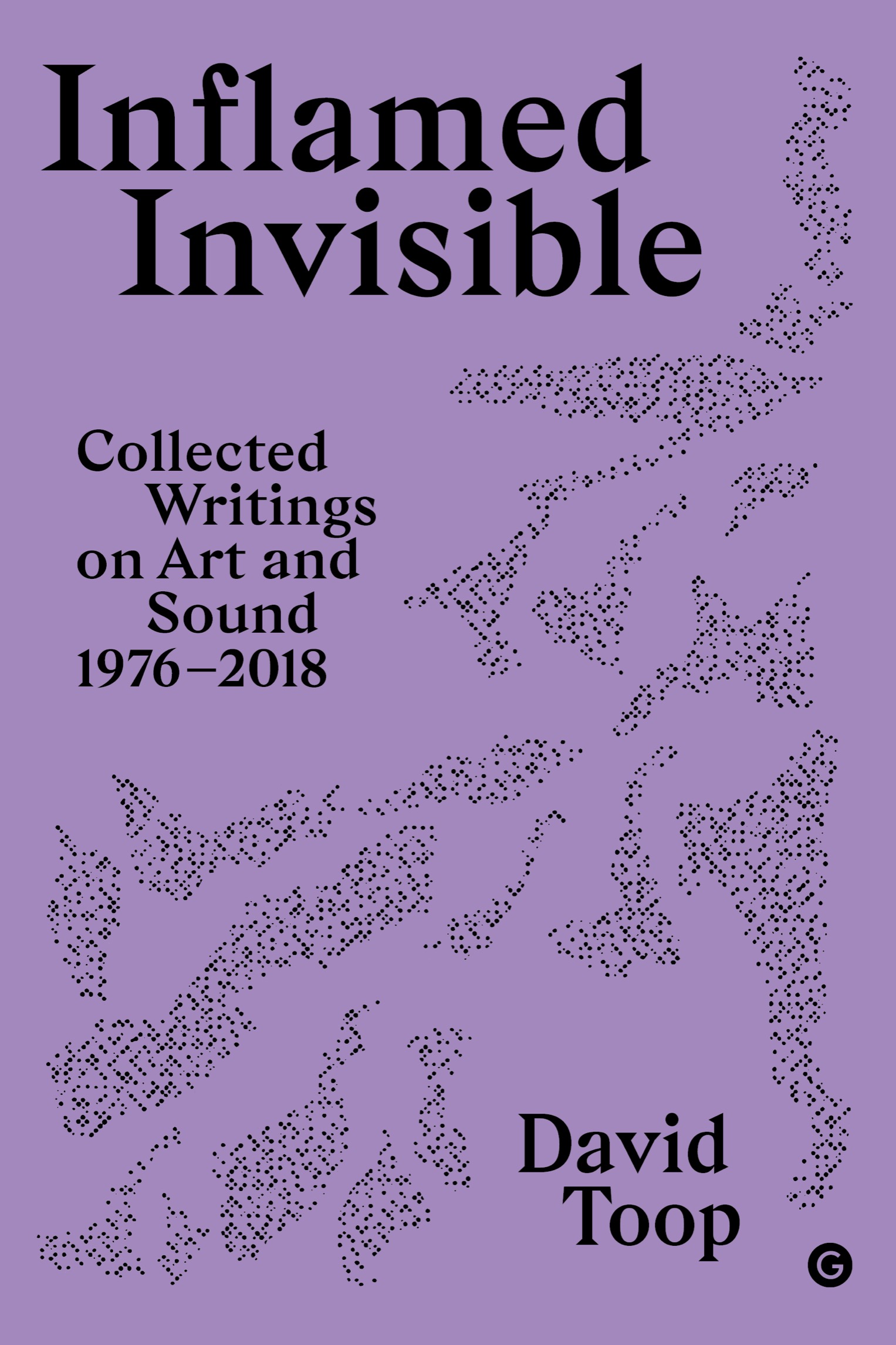

Inflamed Invisible: Collected Writings on Art and Sound, 19762018, David Toop

Goldsmiths Presss Sonics series considers sound as media and as material as physical phenomenon, social vector, or source of musical affect. The series maps the diversity of thinking across the sonic landscape, from sound studies to musical performance, from sound art to the sociology of music, from historical soundscapes to digital musicology. Its publications encompass books and extensions to traditional formats that might include audio, digital, online and interactive formats. We seek to publish leading figures as well as emerging voices, by commission or by proposal.

Inflamed Invisible

Collected Writings on Art and Sound, 19762018

David Toop

2019 Goldsmiths Press

Published in 2019 by Goldsmiths Press

Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross

London SE14 6NW

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

Distribution by The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Copyright 2019 David Toop

The right of David Toop to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with section 77 and 78 in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews and certain non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-912685-16-5 (hbk)

ISBN 978-1-912685-17-2 (ebk)

www.gold.ac.uk/goldsmiths-press

d_r0

Contents

This is a book about music and sound. We wanted to bring the print text to sonic life. We have compiled a series of web links to take you to recordings of the music, musicians, and artists David Toop describes, as well as to artists websites. These tracks and links are listed at the end of the book.

We have placed bar codes in the margins, so you can listen to the music written about as you read. These codes can be scanned by a smartphone camera. On some phones, the built-in camera app will automatically recognize a code. On other phones, you would need to download a QR code reader app.

We have endeavored to find as much of the music online as possible, whether it has been commercially released or not. Many of the links take you to the Discogs database. There, scrolling down, you will find links to videos and audio on YouTube. Other links take you to the artists gallery website or personal site.

For the music that is commercially available, we have compiled an Inflamed Invisible playlist on the Spotify music streaming service. The playlist is accessible here:https://open.spotify.com/user/atau/playlist/6ksANkcLBAuBVsSIgEKClcIndividual tracks from this playlist are seen as Spotify codes at the bottom of the page. To scan the codes and listen to the tracks, please download and use the Spotify app on your phone. Select the magnifying glass icon to search, click again on the search box, then select the camera icon and scan the code.

Wishing you a sonic reading and listening,

Atau Tanaka

Sonics series editor

Inflamed Invisible collects together in one volume a selection of my essays, reviews, interviews, profiles, lectures, blogs and experimental texts on the subject of sound and art the ways in which these two categories of art making have been entangled both historically and in the present when this intensely close relationship is better known as a relatively new category called sound art.

What obsessed me in the early 1970s was a possibility that music might no longer be bounded by the formalities of an audience: the clapping, the booing, the drinking, the short attention span, the demand for instant gratification. Thinking more expansively about sound and listening as foundational practices in themselves led music into unknown and thrilling territory: stretched time, stretched fences and wilderness spaces, under the water of swimming pools, ruined buildings, video monitors, bus journeys, singing sculptures, tactile electronics, weather, meditations, vibration and the interior resonance of objects, autonomous sonic devices, interspecies communications, sine waves, explosions, improvisations, instructional texts, silent actions and the strange rituals of performance art.

The situation was complicated further by musicians seeking a foothold within the art world along with energetic hybridisations of previously self-contained art practices: poetry becoming electronic music, for example, or film becoming practice-as-theory.

When I began writing about art and sound outside my own practice there was no existing category explicitly named sound art, only (still youthful) ancestors such as Alvin Lucier, Max Neuhaus, Atsuko Tanaka or Annea Lockwood whose work specialised in the behaviour and conditions of sounding phenomena. Art was in a state of flux with many emergent styles asserting themselves. It was clear that sound and listening practices were implicated in certain examples of video art, experimental film and theatre, performance art, text scores, land art, sculpture, kinetic art and site-specific installations of diverse forms. Even the most cursory glance at documented work by (among many others) Nam June Paik, Joan Jonas, Robert Rauschenberg, Marina Abramovic, Joseph Beuys, Alison Knowles, John Latham, Yoko Ono, Michael Snow, Charlotte Moorman, Mieko Shiomi or Merce Cunningham shows up early examples.

This transition from music into less certain territory was so gradual as to be imperceptible. Speaking personally I felt an accumulation of stimuli, all of which set out challenges to orthodox categories of practice. They included viewings of Tony Conrads Flicker at the Electric Cinema in Portobello Road, John Lathams Speak during the Hornsey College of Art sit-in of 1968, Michael Snows Wavelength at the Kentish Town incarnation of the London Film-Makers Co-op and Dick Fontaines film of John Cage and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Sound??, shown on British television in 1966. At Watford School of Art in 1968 I sat in a small music room and heard Christian Wolff perform his composition, Stones; on record I heard The Glass World of Anna Lockwood and at a Bond Street gallery watched one of Jean Tinguelys noisy sculptures flailing itself to death. There were many of these experiences, a high proportion encountered in the company of the artists with whom my own musical and conceptual experiments were entangled in the early 1970s Marie Yates, Paul Burwell, Carlyle Reedy, Bob Cobbing, Hugh Davies and others all of them adding to a sense that sound, silence and listening were in a slow process of becoming detached from familiar associations with the world of music.