Table of Contents

Contents

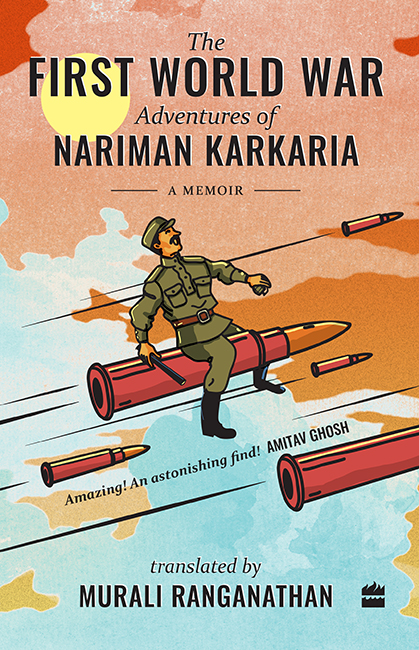

I met Murali Ranganathan for the first time on 21 June 2011 in Mumbai, at an event for my recently published novel, River of Smoke, which is the second book in the Ibis trilogy. I had then just begun working on the last book in the trilogy, Flood ofFire, which is set largely in Canton (Guangzhou). When I learnt that Murali was a historian and translator, specializing in Gujarati and Marathi, I wasted no time in asking him if he knew of any nineteenth-century travel accounts of China by Parsi merchants.

To my great surprise, Muralis response was, yes, he did know of some such accounts, written in Gujarati. I was taken aback because I had been searching for such accounts for a long time and had not been able to find any (I was handicapped, of course, by my lack of Gujarati). I was initially sceptical, but Murali soon proved that he knew what he was talking about by sending me a list of travelogues written by Parsi merchants.

I was, I must admit, both disappointed and hugely impressed. The first because it was frustrating to know that these books existed but were written in a language I cannot read; the second because I knew from experience that to dig out sources like these takes real persistence and archival skill. The researchers who are equipped with the requisite abilities are almost always attached to universities, so it came as a surprise also to learn that Murali did not have any such affiliationindeed, one of the striking things about him is that despite his immense learning, he does not seem the least bit professorial.

I soon learnt that Murali is a scholar in a much older mould, of a breed that is increasingly rare in todays highly compartmentalized world: he is an independent autodidact who has developed his formidable linguistic and archival skills largely on his own. He works on texts in Gujarati, Marathi, Urdu, Hindi, and no doubt, many other languages, and possesses a truly encyclopaedic knowledge of nineteenth-century India. What is more, his scholarly work is driven not by a desire for advancement, but by a genuine passion for the subject. If the world were a more discerning place, Murali would be a celebrated scholar, notable not only for his work, but also for the fact that he has chosen to be free of institutions.

A year later I was in the thick of writing Flood of Fire, which is, in large part, about the experiences of Indian sepoys who fought in the First Opium War. In researching the book, I discovered that even though millions of Indian sepoys fought in the armies of the British Raj, between the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, first-hand accounts of their experiences are vanishingly rare: indeed, the best known of them, From Sepoyto Subedar, may well be apocryphal. It was not till the First World War that accounts of warfare, from the sepoys point of view, began to appear. Given the paucity of the materials, these became some of the most important background readings for Flood of Fire.

In the summer of 2012, I wrote to Murali hoping that he, with his extraordinary archival skills, would be able to find some accounts written by the Marathi soldiers who fought in the First World War. Three months later, on 9 October, I received this letter from Murali:

Dear Amitav,

I havebeen looking for clues to answer your questions regarding Marathasoldiers and the First World War for the last fewmonths but I have not got anywhere near answering themwith any confidence.

In the meanwhile, I was also infectedby travelogitisand the only palliative was to run throughas many travelogues as I could, the constraints being thatthey had to be from the nineteenth century and innon-English Indian languages I know. Among other things, thereis something I found that could be of interest toyou. Allow me to intrude on your time.

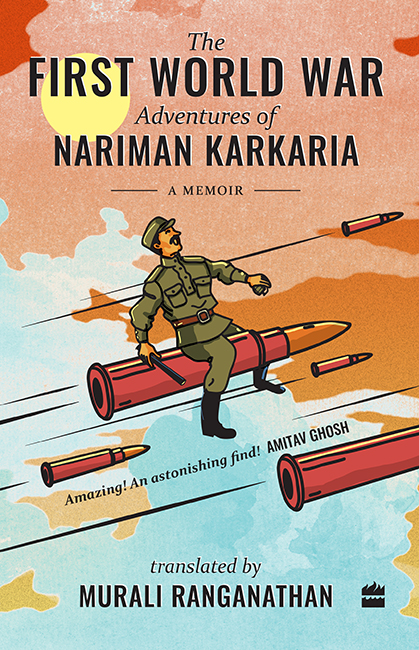

Nariman Karkaria,a young Parsi from Gujarat, had apparently always wanted tosee the world. Sometime in1910,when he was inhisteens,he left home with fifty rupees inhis pocket to do just that. He eventually made hisway to China, travelled, among other places, to Peking andthen to Japan, when somebody suggested that he might aswell travel to Siberia since he was so near. Andthats what he did. He eventually made his wayacross Siberia to St Petersburg and then on to Finlandand Norway, and eventually reached London, I think, sometime in1914 or 1915 (he is not very strong on dates). Another long-standing desire of his was to see awar and he wasnt going to let pass anopportunity which suddenly presented itself. He went to Whitehall tovolunteer but they shooed him away since he was anIndian and suggested he join some desi regiment. He, however, managed to eventually register as a Private with the24thMiddlesex in its D Company, and thusbecame aTommy, as he proudly announces.

The remainingpart (about two-thirds) of the book is the typicalWWI storyNo food, no water, no sleep, no relief. Incredibly, he saw action on three fronts in the nextthree years. In 1916, he was at the Battle ofthe Sommeand describes life in the trenches in vivid detail. He was lucky not to die (most of the othersnear him did) and was sent back to London toconvalesce from an injury. After the usual recovery period andsome weeks of training, he was sent off to theMiddleEasternFrontwhere, after many trials and tribulationsin Egypt, he was part of the Battle of Jerusalem (1917). He describes the triumphant entry into the city bythe British forces. He was then moved to the BalkanFrontwherehe wasin Salonika with the31stCCS;with the British Army, he later travelled through many partsof European Turkey. He was eventually discharged and returned toIndia after five years of travel and adventure.

He, presumablyon public demand, wrote this book which was published in1922 by D.A. Karkaria from the Manek PrintingPress in Mumbai. It is deceptively titled Rangbhumi par Rakhad, which I would translate as Sorties on Stage. Itwas perhaps intended as a pun forjangbhumi, aword he uses often in the text.

In spite ofthe extreme trauma he endures over many pages, there isa certain Wodehousian aura which permeates the whole book. Thestiff upper lipis palpable and sometimesWhat ho!is almost audible.

I must confess I have notread the book in toto but have merely flipped throughit to glean the bare outlines of his career. Thereis much more to his book and I might bewrong with regard to details as I am writing frommemory. There are many photographs both from his travels andfrom the war. I am not sure if he tookthem himself but some of them are intimatesoldiers bathingin the nude at an oasis with camels for company