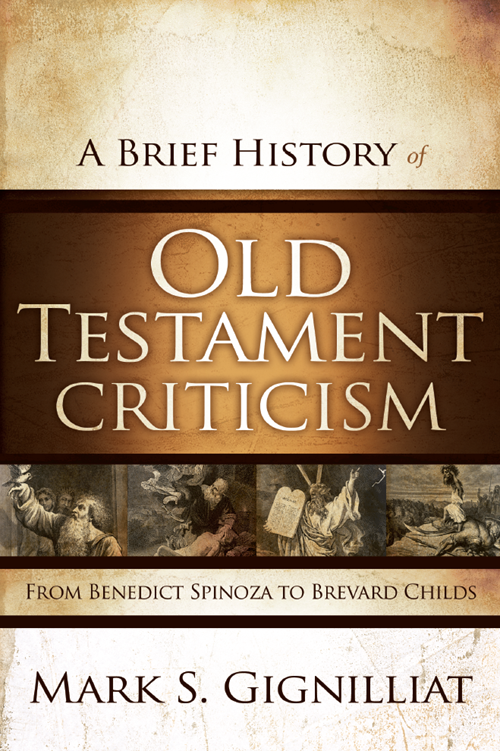

A B RIEF H ISTORY of

O LD

T ESTAMENT

CRITICISM

F ROM B ENEDICT S PINOZA TO B REVARD C HILDS

M ARK S. G IGNILLIAT

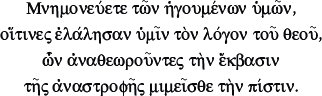

Dedicated to

Michael P.V. Barrett

HEBREWS 13:7

W HEN I BEGAN MY POSTGRADUATE WORK IN BIBLICAL STUDIES, I DID SO like many who exit from an evangelical seminary. My knowledge of the biblical languages was decent. I could analyze a Hebrew sentence, parse the verbs, make sense of the syntax by appealing to Waltke and OConnors massive tome, and even engage the textual-critical issues involved. In retrospect, my knowledge in these areas was not as deep or wide as I might have thought at the time. Still, I had the rudimentary skills necessary for the exegesis of the biblical text, and, wisely or unwisely, they admitted me for postgraduate work.

What I discovered during the first year of my doctoral studies, in addition to the imposter syndrome that haunted me, wondering when my doctoral supervisor would tap me on the shoulder and say, Im sorry; weve made a terrible mistake and you need to go home, was my woeful lack of knowledge in the history of Old Testament interpretation and criticism. This is not a reflection on my seminary teachers; one can only cover so much in class. We read Dillard and Longmans Introduction to the Old Testament. The names Wellhausen and Gunkel were not foreign to me. Still, my knowledge of these figures, their methods, and location in the history of ideas was thin at best.

I will not project my story on everybody, but I imagine my experience is common. With great interest and relief, I read Richard Schultzs account of his first years of postgraduate studies at Yale under Brevard Childs.texts and a flimsy working knowledge of higher critical figures and theories. I read his essay and thought, Maybe I should write a short history of Old Testament criticism targeted at students. Well, here it is.

This is a book for students. A student is not limited to someone enrolled in a formal class setting, though I definitely have this in mind. Nor is this book only for those wishing to do postgraduate studies. The intended audience of this book is anyone who is interested in the Bible, its history of interpretation, and the particular problems and approaches to Old Testament studies in the modern period. I do hope the book will be of some benefit to those whose knowledge of Old Testament criticism goes beyond that of a students. But I had to fight the temptation at every turn to allow this book to take on a life of its own, becoming something other than what was originally conceived. In places, I am sure I have failed in this regard.

A few words should be said about the scope and structure of the book a road map, if you will, for the reader and teacher. Let me say on the front end what this book is not. This book is by no means a comprehensive attempt at expounding the very complex history of Old Testament interpretation. This kind of project is underway now with the magisterial work Magne Saeb is editing titled Hebrew Bible/Old Testament (HBOT). All this to say, the book you are holding is a toes dip in a very large pool.

I have decided to focus on major figures in a picture gallery tour of sorts. My rationale is simple. People and their ideas are more interesting (at least to me) than abstract discussions of critical theories. For example, I do not have a chapter on form criticism. But I do have a chapter on Hermann Gunkel, with form criticism discussed therein. Also, I find these figures fascinating as people located in the broader cross-stream of ideas, cultural norms, and ecclesiastical battles. At the same time, the context provided for these figures could surely be expanded. The chapters follow the classic genre of life and work. I will discuss briefly the life and setting of the figure and then explore an aspect of their contribution to Old Testament criticism.

There are dangers with the particular historiographical approach I have taken. Saebs introductory article in HBOT labels one of these dangers personalism, and he warns against focusing so much on well-known scholars that the textured nature of Old Testament interpretation will be flattened. In other words, focusing solely on the famous pictures in a museum may cause the patron unwittingly to miss the multifaceted beauty and complexity of other paintings and influences from the same period of art history.

Saebs is a fair warning, and one I take seriously. I have tried to provide some historical, social, and intellectual context for the figures described. Still, the dangers of personalism are present in this volume and can be remedied by further study for those interested. I want students to understand some of the major currents of Old Testament criticism, beginning in the modern period and continuing to the work of Brevard Childs. To do this, I have focused on particular figures. Without doubt, the chapters demand more nuance than is currently presented, but I hope the reader will take this books stated intention into account whenever frustration occurs.

One may ask how someone can write even a brief history of Old Testament criticism and not include, say, Jean Astruc, Johann David Michaelis, Richard Simon, Johannes Semler, Robert Lowth, J. G. Eichhorn, Abraham Kuenen, Wilhelm Gesenius, Bernard Duhm, Hugo Gressmann, Walther Eichrodt, Martin Noth, or James Barr (to name but a few). I feel the full weight of this criticism and can only ask the informed readers forgiveness. My rationale is simple: (1) I want the volume to remain small and accessible for students; (2) I believe the figures in this work represent the larger trends and tendencies of Old Testament criticism in the modern period; and (3) I wanted to finish.

As will become apparent, I am not a neutral observer of the history of Old Testament criticism. The detaching of a robust doctrine of revelation from the material study of the Old Testament, a hermeneutical instinct one finds poignantly present in Baruch Spinoza, has had a deleterious effect on the study of the Old Testament as Scripture. Here my cards are already on the table, are they not? I do not want to make villains of the usual suspects in this volume. In fact, the reader may sense my deep sympathies for the intellectual and spiritual difficulties faced by some of these figures. Still, I have a working understanding of the Old Testament as Christian Scripture that not only informs my reading but in fact determines and shapes the way I approach it. I am not neutral. But my lack of neutrality when it comes to Old Testament hermeneutics is located in an Anselmian epistemology credo ut intelligam: I believe so that I may understand and a confessional posture. That said, I do hope readers find a fair presentation of these figures lives and work. This has been my aim.

I will return to these matters in the conclusion. For now, let me introduce you to Benedict Spinoza.

I actually did postgraduate work on Paul and Isaiah, spending equal amounts of time in New Testament and Old Testament exegesis.

Richard Schultz, Brevard S. Childss Contribution to Old Testament Interpretation: An Evangelical Appreciation and Assessment, Princeton Theological Review 14 (2008): 7172.

Magne Saeb,