Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

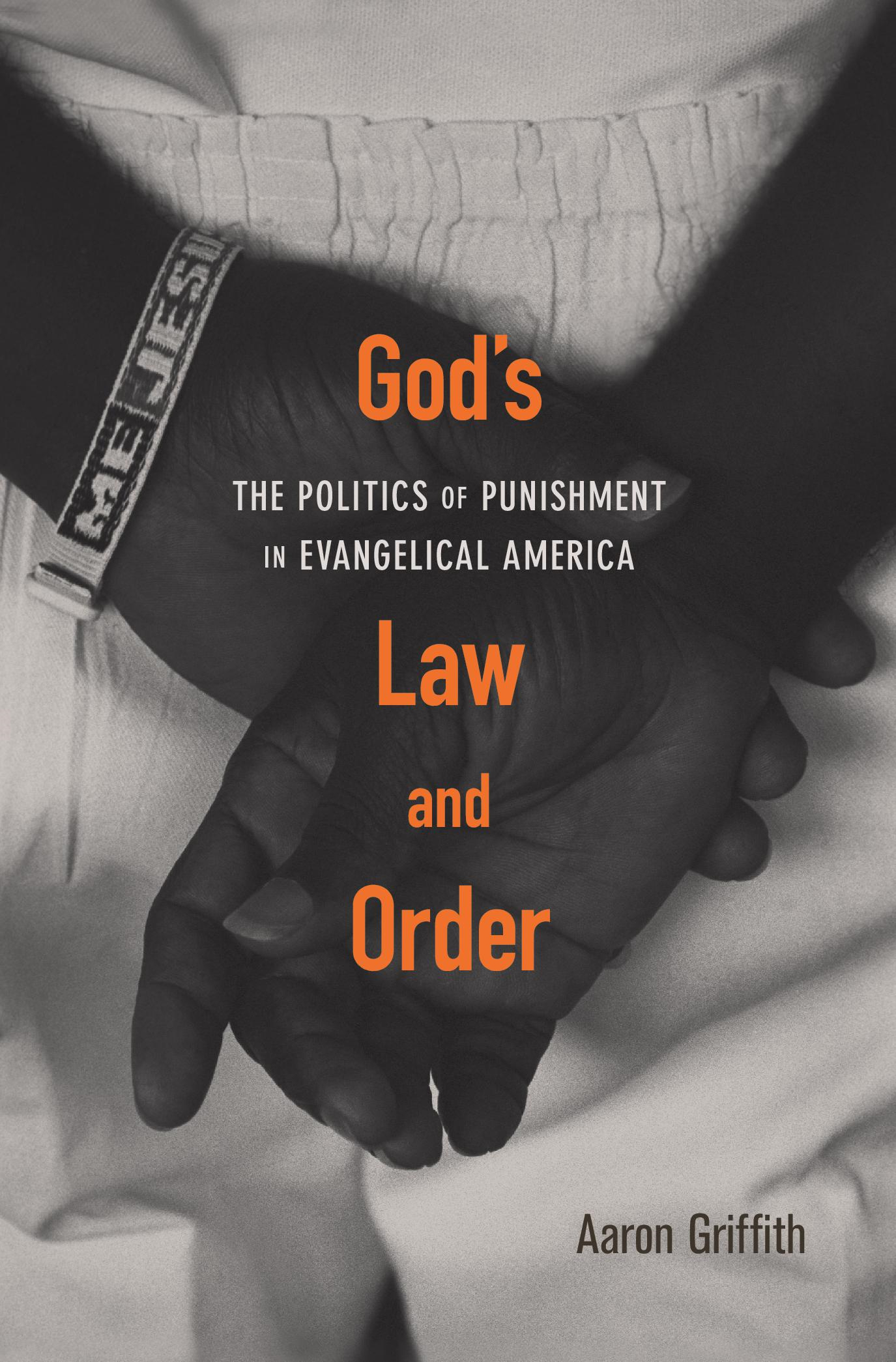

Gods LawOrder

THE POLITICS OF PUNISHMENT IN EVANGELICAL AMERICA

AaronGriffith

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England

2020

Copyright 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover photograph by Charles Ommanney/Getty Images

Cover design by Lisa Roberts

978-0-674-23878-7 (cloth)

978-0-674-24975-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24976-9 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24977-6 (PDF)

Publication of this book has been supported through the generous provisions of the Maurice and Lula Bradley Smith Memorial Fund

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Griffith, Aaron, 1985 author.

Title: Gods law and order : the politics of punishment in evangelical America / Aaron Griffith.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016859

Subjects: LCSH: EvangelicalismUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Criminal justice, Administration ofUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Church and stateUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC BR1642.U6 G75 2020 | DDC 261.8/33609730904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016859

For Eliza

CONTENTS

Get ready to see Jesuss face. The chariots here to get you.

Lying on his deathbed, Antonio James listened to these comforting words from a caring Christian friend. James calmly welcomed the words, whispering Bless you in reply. Yet immediately after the soothing friend spoke, he motioned to some technicians standing nearby. This was the sign that they could begin injecting poisonous chemicals into Jamess body, which had been strapped down to prevent resistance. These chemicals would sedate James, relax his muscles, and finally stop his heart, abruptly ending his earthly life even as they began his heavenly rest.

It was Burl Cain, the warden of the famed Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola, who had been Jamess spiritual confidant at the end of his life. Cain was proud of this role. It was his opportunity for a second chance, he confessed to a crowd at Wheaton College, after he had failed to minister to another condemned prisoner. In this earlier case, Cain had ignored the mans fear, callously signaling the technicians to begin the injection process without offering an evangelistic word or spiritual support. As he spoke in Wheatons chapel service, Cain admitted to students that he was later horrified by what he did: Not that we had executed him so much but because [I] didnt use the opportunity to do the right thing.

Even before resigning his post in 2016 after allegations of suspicious real estate dealings came to light, Cain was a very controversial figure. The gathered evangelical community at Wheaton was either unaware of any controversy regarding Cains work or simply did not care. Students offered him a standing ovation at the conclusion of his message, while the colleges Christian outreach office continued to send students on spring break mission trips to Angola.

This is not a book about Burl Cain and the unique evangelistic disciplinary regime at Angola. Cain has been the focus of other works, and as a state warden who used his official position to evangelize and pray with prisoners, he is largely exceptional. Instead, this book is about the history behind the deeper sentiments underlying his message and its reception. It is about a quintessentially American gospel and law amalgamation, the work of soul-saving witness and spiritual concern within the context of severe punishment, all of which characterized evangelical influence in prisons and criminal justice in the twentieth century. Indeed, this book is just as much about the enthusiastic applause from the Wheaton students assembled to hear the grizzled, plainspoken warden preach as it is about the conceptual framework that informed him. There was something in Cains message about gospel and law that confirmed what the young evangelical vanguard at the Harvard of Christian schools knew to be true about their inherited faith, a conceptual affinity that united American evangelicals across generations, culture, theology, and region.

This book is a religious history of mass incarceration. It charts the influence of evangelicals in American criminal justice from approximately the end of World War II to the present (though with important roots in preceding decades). This was a time when arrest and imprisonment rates rose exponentially, the result of new law and order currents in American culture; more aggressive policing, prosecution, and sentencing strategies; and the abandonment of rehabilitative penal practices for more retributive ones. The shift can be seen in a comparison of imprisonment rates from 1972, when 161 US residents were incarcerated per 100,000 population, to 2010, when 767 were incarcerated per 100,000. This resulted in a prison and jail population that now numbers as many as 2.23 million people (and the worlds highest incarceration rate).

Crime and punishment mattered so much for evangelicals because their religious outlook meshed well with important aspects of Americas penal culture. Simply put, there were historical reasons why Wheaton students applauded Cain so vigorously. For example, early postwar evangelicals saw religious value in emerging conceptions of crime, as when Billy Graham denounced American sin with reference to rising public concerns about juvenile delinquency. They channeled broader shifts in American religious culture into daily prison life, through evangelistic literature given to inmates and inspirational sermons preached by visiting prison missionaries in the 1970s. And their robust sense of Gods forgiveness and grace led certain evangelicals to champion inmate restoration and prison reform programs in the 1980s and 1990s. In some ways this compatibility was a return to form, as evangelicals ranked as Americas original criminal justice pioneers in their antebellum penitentiary construction and reform. And like evangelical social engagement in antebellum prisons, this present consonance has a complicated legacy: evangelicals have simultaneously proved complicit in the American justice systems most grievous problems even as they have also been pioneers in humanitarian engagement with modern prison life.

Though this book charts the story of modern evangelical crime and prison concern through several chronological and interpretive lenses, it presents three broad arguments about the intersection of evangelicalism and mass incarceration. These arguments try to make sense of the confluence of sympathetic piety and punishment as seen in figures like Burl Cain, and the striking correspondence this seemingly paradoxical integration had with broader evangelical culture.

First, crime and punishment simply mattered for evangelicals in the latter half of the twentieth century and were central to their entry into American public life. Evangelicals were on the cutting edge of engagement with American criminal justice, prisons, and reform, outpacing nearly all other American religious and social constituencies in their interest, intensity, and influence. They used crime as a rhetorical frame, led the way on all sides of the political battles around mass incarceration, and were very active in shaping the religious culture of prisons themselves. One cannot understand the creation, maintenance, or reform of modern American prisons (or how someone like Burl Cain could have appeared on the scene) without understanding the impact of evangelicalism. Each facilitated the rise of the other.