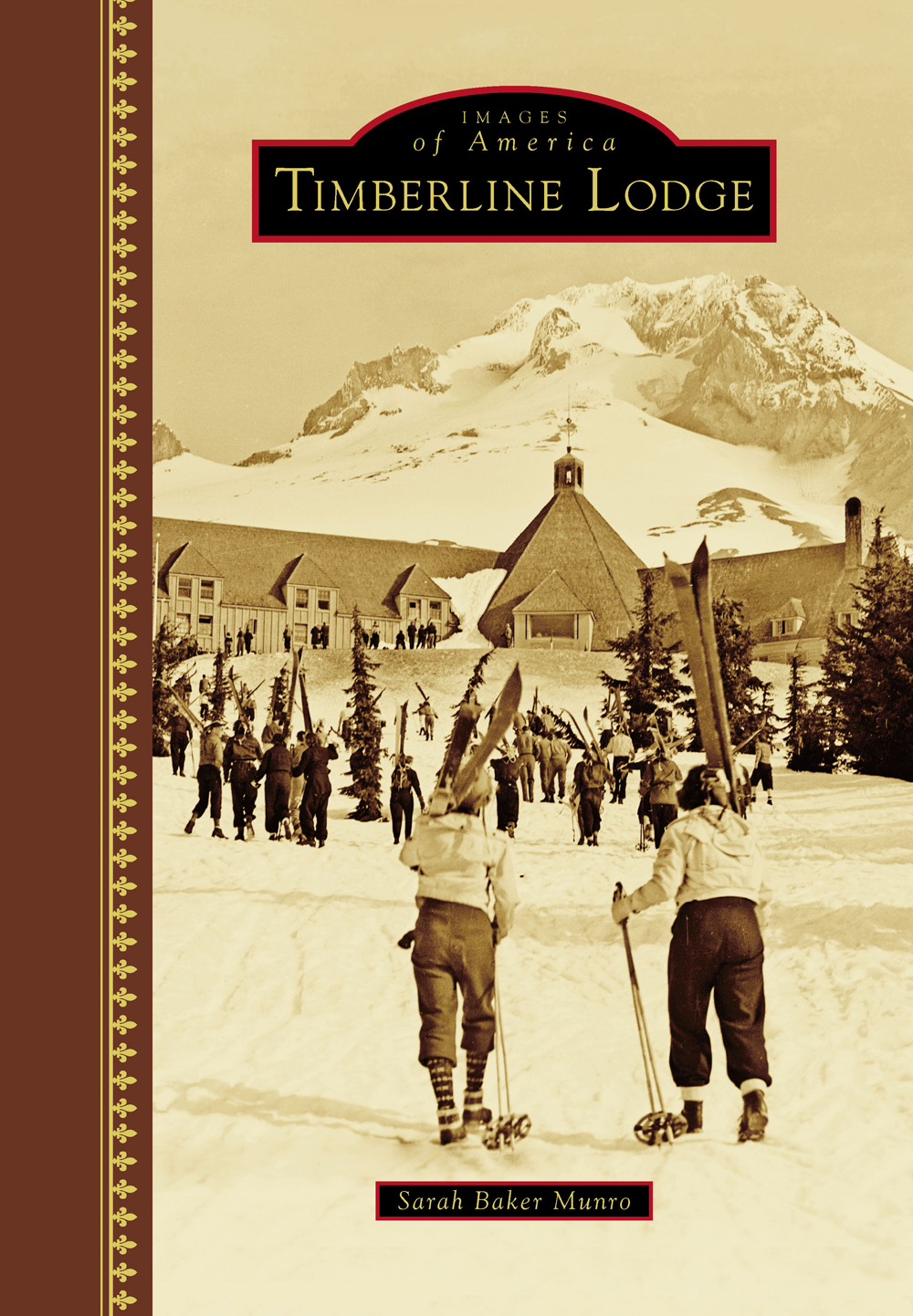

IMAGES

of America

TIMBERLINE LODGE

The rustic architecture of the US Forest Service in the 1930s contains elements shown here in the bison head carved on the log end below the eaves, the stone facing, and the shake roof on the exterior of Timberline Lodge. Among others, Albert D. Taylor, president of the American Society of Landscape Architects, codified this style. Rustic architecture features local, natural materials such as wood and stone, handcrafted embellishments, and a design in a scale compatible with the landscape. (Friends of Timberline.)

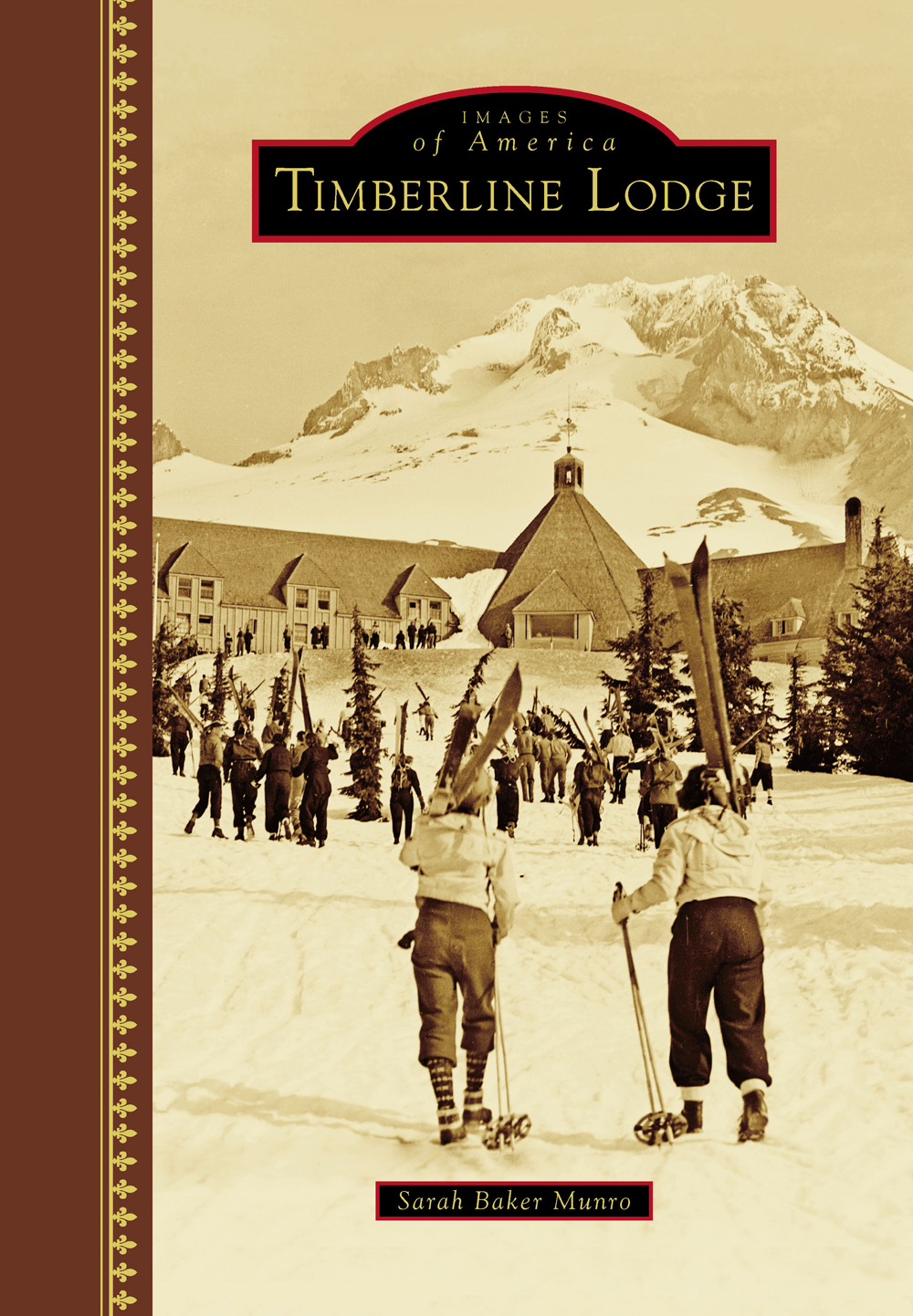

ON THE COVER: When Timberline Lodge opened in 1938, it immediately became a ski destination. When the Magic Mile ski lift was completed in 1939, it was the second chairlift in the United States. In April 1939, Mt. Hood hosted the US National Downhill and Slalom Ski Championship tryouts for the US Olympic Team. These women skiers walking toward the lodge are probably participating in those competitions. (Photograph by Everett Olmstead; Thomas Robinson.)

IMAGES

of America

TIMBERLINE LODGE

Sarah Baker Munro

Copyright 2016 by Sarah Baker Munro

ISBN 978-1-4671-2386-0

Ebook ISBN 9781439658680

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934562

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Charles E. Heaney was an Oregon artist employed under the Works Progress Administration between 1937 and 1939. Heaney created 64 paintings and nine woodcut editions under the WPA, according to Roger Hulls Charles E. Heaney: Memory, Imagination, and Place (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005). The Mountain, among Heaneys finest oil paintings, was commissioned for Timberline Lodge (see ). This bookplate was created from one of Heaneys woodcuts of the lodge. (Friends of Timberline.)

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Photographs for this history were gathered from and are used courtesy of Alex Blendl Historic Photographs; DiBenedetto/Thomson/Livingstone Architects; the Friends of Timberline archive (FOT); Jeff Thomas; Mt. Hood Cultural Center & Museum (MHCCM); Federal Highway Administration; National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection; Oregon Historical Society Research Library (OHSRL); Oregon State Library (OSL); Oregon State University Libraries; Portland Art Museum Library and Archives (PAMLA); Ray Atkeson Image Archive; Thomas Robinson, Historic Photo Archive; and US Forest Service, Mt. Hood National Forest (USFS, Mt. Hood). The term Forest Service throughout refers to the US Forest Service. Copies of many photographs are available in multiple locations. One accessible source is the Oregon State Library, and an image here made from a print in the Friends of Timberline archive is sometimes credited to the Oregon State Library.

I am grateful for generous assistance provided by Alex Blendl; Scott Daniels and Geoff Wexler, Oregon Historical Society Research Library; the late A.P. DiBenedetto; Robert Hadlow, Oregon Department of Transportation; Maggie Hansen and Katie Moss, Portland Art Museum; David Hegeman and Sara Belousek, Oregon State Library; Aaron Johanson; Randi Black, Lenore Martin, Michael Madias, Jeff Jaqua, and Friends of Timberline; Lloyd Musser, Mt. Hood Cultural Center & Museum; Wade Myers, National Park Service; Chris Petersen, Oregon State University Libraries; Thomas Robinson; Scott and Susan Russell; Rick and Teresa Schafer, Ray Atkeson Image Archive; Jeff Thomas; Jon Tullis, Linny Adamson, and R.L.K. and Company; and Alexandra Wenzl, US Forest Service, Mt. Hood National Forest. Notes on construction and photographs provided to the Friends of Timberline archive by the late Ward W. Gano were invaluable. George M. Hendersons Lonely on the Mountain: A Skiers Memoir (Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing, 2006) is filled with first person experiences from the construction of the lodge through the 1960s.

The encouragement and direction provided by Katelyn Carter, Caitrin Cunningham, Tim Sumerel, and other editors at Arcadia Publishing brought this book into existence; I am indebted to them for their assistance. Many sources were consulted and many individuals assisted in the preparation of the manuscript, and although some are unnamed, I am very appreciative of their help.

INTRODUCTION

Timberline Lodge stands 6,000 feet above sea level on Mt. Hood in Oregons Mt. Hood National Forest. This popular destination welcomes almost two million visitors annually. It offers year-round skiing and snowboarding. Hiking and climbing also draw many visitors to the lodge. Many, however, come to revel in its beauty and charm. The lodge is a premier example of Works Progress Administration (WPA) architecture, a masterpiece of the rustic style, steeped in the tradition of Arts and Crafts. It blends into its setting so completely that it is almost impossible to imagine Mt. Hood without it, but the construction and the furnishing of a recreational hotel with public funds during the Depression were unprecedented.

The impetus for Timberline Lodge is embedded in the policies on uses of public lands, the development of roads on the mountain, and the growth of recreation in the forest. Timber, grazing, and clean water were priorities when the national forests were created, but by 1920, the Forest Service expanded its focus to include recreation. Frank Albert Waugh, an eminent landscape architect, wrote Recreation Uses in the National Forests after visiting national forests across the country. The report paved the way for improving access to the Mt. Hood National Forest and encouraging construction of new lodging facilities to accommodate skiers and hikers. The Mt. Hood Loop Road, under construction from 1919 to 1925, provided access to automobile travel around the mountain. Back then, the loop road was not kept open in the winter.

What is now called the Historic Columbia River Highway forms the north side of the loop road and was built between 1913 and 1922. Although there were others, two lodges in particular along this leg attracted tourists in the 1920s: the Multnomah Falls Lodge, which was built in 1925 and provides dining and other amenities, and the Columbia Gorge Hotel, developed in 1904 to deliver services to steamship travelers. Further along, on the east side of Mt. Hood, the loop road passes by a road into the national forest where Cloud Cap Inn, built in 1889, still stands. With the increase in visitors after the loop road was finished, interest focused on constructing a larger lodge near Cloud Cap, on the northeast side of Mt. Hood. Proposals included building a tram to the summit. In order to evaluate this proposal, the Forest Service sponsored a report published in 1930 as Public Values of the Mount Hood Area. Then secretary of agriculture William M. Jardine considered Mt. Hood of such importance that he declared, We are dealing with one of the great landmarks of the continent.

While lodge development was under consideration on the north side of the mountain, skiers began to organize ski competitions on the south side of Mt. Hood. Interest in a ski lodge soon shifted from the north to the south side of the mountain. The Forest Service recreation officer identified a site for development approximately where Timberline was eventually built. The site was six miles above Government Camp. A dramatic contemporary design was proposed near this site by a young Portland architect, John Yeon, and then, in the face of the Depression, no funds were available for construction of the lodge either by the Forest Service or privately.

Next page