COIN FINDS IN BRITAIN

A COLLECTORS GUIDE

Michael Cuddeford

The obverse of a silver groat of Edward III.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

The reverse of an Iron Age gold stater.

CONTENTS

A range of coins dating from the late Iron Age to modern times, all typical of single finds from farmland.

BRITAINS BURIED COINAGE

C OINS HAVE BEEN used in Britain for over two thousand years, and throughout that period have been lost, discarded or deliberately buried. Over the centuries, successive generations have found such coins from earlier times in the course of farming or building activities, and since the nineteenth century have actively sought them through archaeology and, more recently, metal detecting. This book is intended to act as a guide to the range of coins to be found buried in the soil of Britain, and to categorise them broadly according to type and historical period. The thing that probably surprises people the most is the sheer volume of early coins that have found their way into the buried historic landscape. On some Roman sites coin finds may number in the hundreds or even thousands, and even in landscapes of no obvious historic importance early coins may still be surprisingly prolific. So how do coins come to be buried in the first place?

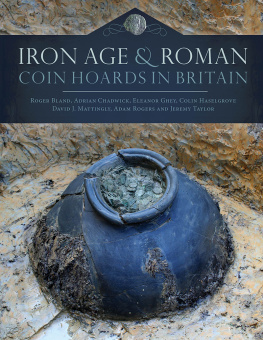

Deliberate concealment is of course one way, and over the years the media have carried stories of some quite spectacular finds, such as the Hoxne Roman treasure. Other hoards may contain only a handful of coins, but still represent a deliberate attempt by someone to conceal portable wealth from the risk of theft by others. Sometimes hoards are associated with specific periods of civil disorder, such as wars or invasion, and in such circumstances hoards continue to be buried in troubled parts of the world. Hoards, however, are not always the result of concealment for recovery. Just as people throw coins into fountains and wells for good luck, the same superstition was prevalent in ancient times, to the extent that high-value coins and artefacts were buried as votive offerings, with no intention of recovery on the part of the owner. It is now thought that the amazing assemblage of Iron Age gold found at Snettisham in Norfolk, and now in the British Museum, was in all probability deliberately abandoned as an offering to the gods, and this has even been suggested for the Hoxne hoard. It is quite possible that many smaller coin hoards were also votive deposits, rather than concealed with the intention of later recovery.

A hoard of Roman gold solidi, dating from the late fourth to early fifth century AD. Found in Essex (average diameter 21 mm).

Not all hoards are large and spectacular these three early Saxon pennies (late seventh to early eighth century AD) were found in close proximity, but loose in ploughsoil. They were subsequently declared Treasure (actual size 12 mm).

However, most coins that are found by archaeologists or members of the public are single finds, of which the majority will be casual losses. That this happens can be seen by looking around on the ground by vending machines and parking meters, where odd coins can occasionally be spotted. Many ancient coins were a lot smaller and lighter than modern ones, and, even allowing for people taking more care of them, an amazingly large number seem to have been lost. Of course, just as some hoards were buried for votive purposes, the same is probably true of single coins, which may have been deposited at sacred sites in some quantity. If, for example, a metal-detector user recovers a number of coins with a date range spanning several centuries in an open field with no obvious archaeology evident, they might be interpreted as casual losses, but in ancient times there could have been a venerated tree or sacred grove at the very same spot, and the coins may have been deliberately placed in and around the site, even though nothing remains in the archaeological record other than the coins themselves. Similarly, a single coin may have been placed in a field or other location as a one-off act of devotion to a particular god or for general good fortune. A very high number of gold coins from the Iron Age have been found as single finds, which means that their owners must have been remarkably careless to lose so many in everyday transactions, unless they were deliberately deposited. In later periods gold coin finds are extremely rare, because they were too valuable for day-to-day transactions. When lower-value coins are found by themselves it is probable that they represent casual losses, but that is not something that we can ever say with certainty.

Where locations produce random scatters of coins covering broad periods, there will probably have been several mechanisms at work at the same time. As already stated, some Roman occupation sites can be extremely prolific, and coins recovered from such sites will undoubtedly derive from small plough-scattered hoards, votive deposits and also casual losses. From the third century AD, Roman coins were produced in vast quantities and during some periods single coins would have been of very little intrinsic value. These were undoubtedly lost through use just as modern small change is lost, and as they were of low value, little effort would have been expended in looking for them. Some may even have been simply discarded when they were rendered worthless in one of the frequent re-coinages of the Roman period. But if we assume that some at least were lost through use, there has to be active trading going on in the first place, and many Roman period sites may have been occupied as nucleated settlements much like later medieval villages, even though the archaeological interpretation is generally to see them as self-subsisting agricultural units. If this latter was wholly the case, it is difficult to see how so many coins could have been lost, if they were not being actively exchanged.

Iron Age gold stater, dating from the first century BC to the first century AD. A single find but possibly a deliberate votive offering (actual size 20 mm).

Typical finds from a Roman period rural site (largest coin 19 mm).

That coins are lost where they are used is demonstrated by the example already cited of small change falling around vending machines, and metal-detector users who search the sites of travelling fairs will usually find a good haul of dropped coins after the fair has moved on. Those who search parkland sometimes find coins in small stacks, lying as they fell, having slipped from the trouser pocket of someone sitting on the grass. Some measure of coin circulation in the seventeenth century can be gauged from the traders tokens that prevailed for a short period. These were issued by local tradesmen, who were normally the only persons who could redeem them for cash. Most traders tokens that occur as field finds are local to the find-spot, with just the occasional one turning up from further away. This demonstrates that, at least in this case, loss was related to locale. However, it is highly likely that a proportion of coins found as single field finds were not originally lost there, but arrived at the location by other means. There are some fields that produce significant numbers of coins of many periods, and yet which have no history of any sort of on-site trading taking place. In ancient times coins were normally carried in purses or pouches, not loose in pockets, if indeed early garments even had pockets, and so they are unlikely to have been lost in the places they are found. The most probable mechanism for the presence of many single coin finds is that of secondary deposition, with the coins being lost elsewhere but being brought to the location in domestic refuse, which was used for manuring fields. Prior to flushing lavatories and domestic rubbish collection, the disposal of human and animal waste was an ever-present problem; the removal of such material, with that from privies being known colloquially as night soil, was undertaken by men employed specifically for the job. The waste was carted out from the cities and into the countryside, where it was made available to farmers for fertiliser. The rural population was probably too small for it to produce enough waste of its own to adequately manure large growing areas, and it may be that many of the coin finds from arable land originally came from an urban centre many miles away. This would certainly explain the occasional find of high-value coins, which probably saw little circulation in the rural economy. This process was probably going on way back in antiquity, and even up to the early twentieth century the amount of horse manure alone that descended daily on to the streets of Britains cities was enormous. Any coin or other small personal item dropped into a privy or on to a manure-covered street was gone for ever, and could be destined to be re-deposited on a field many miles from the place where it was originally lost.