Published in 2018 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2018 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2018 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Andrea R. Field: Managing Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Amelie von Zumbusch: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Series Designer

Tahara Anderson: Book Layout

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Nicole DiMella: Photo Researcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Lucy Sackett, editor.

Title: Islamic literature / [editor] Lucy Sackett Smith.

Description: New York, NY : Britannica Educational Publishing, 2018. |

Series: The Britannica guide to Islam | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016053717 | ISBN 9781680486162 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Islamic literatureHistory and criticism. | Arabic

literatureHistory and criticism. | Persian literatureHistory and

criticism. | Turkish literatureHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PJ807 .I85 2018 | DDC 809/.8921297dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016053717

Manufactured in the United States of America

Photo credits: Cover, p. 1 Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images; p. 9 The Walters Art Museum/W.626.289A/CC0; p. 13 Shinji Shumeikai Discretionary Fund/AC1999.158.1/www.lacma.org; p. 15 The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky/M.73.5.18/www.lacma.org; pp. 26, 102 Heritage Images/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; pp. 29, 38 Pictures from History/Bridgeman Images; p. 33 Lynn Abercrombie; p. 34 Everett - Art/Shutterstock.com; p. 41 British Library Board/Robana/Art Resource, NY; p. 43 Bloomberg/Getty Images; p. 46 Joeri De Rocker/Alamy Stock Photo; pp. 49, 64 Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 53 Bibliotheque de la Faculte de Medecine, Paris, France/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images; p. 56 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 60 Laurie Noble/Photolibrary/Getty Images; p. 62 The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky/M.73.5.410/www.lacma.org; p. 67 DEA/J. E. Bulloz/De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images; p. 69 Private Collection/Bridgeman Images; p. 72 The Walters Art Museum/W.626.94B/CC0; p. 75 Reproduced by permission of the British Library; p. 80 Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum, photograph, J.R. Freeman & Co. Ltd.; p. 82 Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA/Bridgeman Images; p. 89 The Granger Collection, New York; p. 93 Gift of The Walter Foundation/M.91.348.1/www.lacma.org; p. 96 Henry Guttmann/Hulton Royals Collection/Getty Images; p. 106 Courtesy www.eltaher.org; p. 112 Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 116 SZ Photo/Bridgeman Images; p. 120 Thomas Hartwell/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images; back cover, pp. 37 background design javarman/Shutterstock.com; interior pages border design Azat1976/Shutterstock.com.

I t would be almost impossible to make an exhaustive survey of Islamic literatures. There are so many works, of which hundreds of thousands are available only in manuscript, that even a very large team of scholars could scarcely master a single branch of the subject. On top of that, Islamic literatures exist over a vast geographical and linguistic area. This happened because they were produced wherever the Muslims went, pushing out from their heartland in Arabia through the countries of the Middle East as far as Spain, North Africa, and, eventually, West Africa. Persia (now Iran) is a major centre of Islam, along with the neighbouring areas that came under Persian influence, including Turkey and the Turkic-speaking peoples of Central Asia. Many Indian languages have a literature that focuses almost exclusively on Islamic literary subjects. There is an Islamic content in the literature of Malaysia and in that of some East African languages, including Swahili. In many cases, however, the Islamic content proper is restricted to religious worksmystical treatises, books on Islamic law and its implementation, historical works praising the heroic deeds and miraculous adventures of earlier Muslim rulers and saints, or devotional works in honour of the Prophet Muhammad.

The vast majority of Arabic writings are scholarly. The same, indeed, is true of the other languages in which Islamic literature has been written. There are superb historically important translations made by medieval scholars from Greek into Arabic. There are historical works, as well as a range of religiously inspired works. There are books on grammar, style, ethics, and philosophy. All have helped to shape the spirit of Islamic literature in general, and it is often difficult to draw a line between such works of scholarship and works of literature in the narrower sense of that term. Even a strictly theological commentary can bring about a deeper understanding of some problem of aesthetics. A work of history composed in florid and artistic language would certainly be regarded by its author as a work of art as well as of scholarship, whereas the grammarian would be equally sure that his keen insights into the structure of Arabic grammar were of the utmost importance in preserving that literary beauty in which Arabs and non-Arabs alike took pride.

In this treatment of Islamic literatures,however, the definition of literature is restricted to poetry and literary prose, whether popular or courtly in inspiration. Other categories of writing will be dealt with briefly if these shed light on some particular aspect of literature.

In its earliest days, the poetry of the Arabs consisted of praise and satirical poems thought to be full of magical qualities. The strict rules of the outward form of the poems (monorhyme, complicated metre) even in pre-Islamic times led to a certain formalism and encouraged imitation. Another early poetic form was the elegy, as noted in the work of the Arab female poet al-Khans.

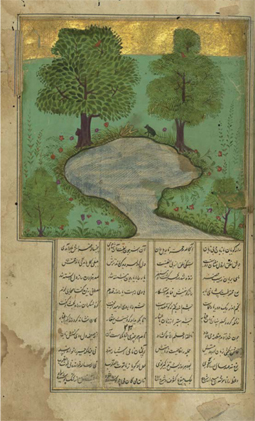

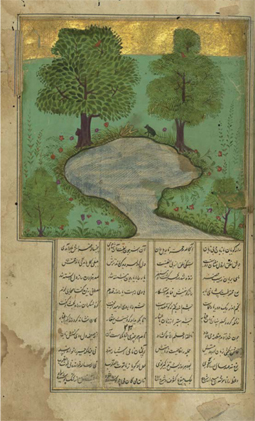

Jalal al-Din Rumi was a Sufi mystic and one of the greatest poets in Islamic literature. This manuscript page comes from a copy of his Ma s nav , a collection of poems.

For the most part, however, Goethes statement that the stories of The Thousand and One Nights have no goal in themselves shows his understanding of the character of Arabic belles lettres, contrasting them with the Islamic religion, which aims at collecting and uniting people in order to achieve one high goal. Poets, on the other hand, rove around without any ethical purpose, according to the Qurn. For many pious Muslims, poetry was something suspect, opposed to the divine law, especially since it sang mostly of forbidden wine and of free love. The combination of music and poetry, as practiced in court circles and among the mystics, has always aroused the wrath of the lawyer divines who wield so much authority in Islamic communities. This opposition may partly explain why Islamic poetry and fine arts took refuge in a kind of unreal world, using fixed images that could be correctly interpreted only by those who were knowledgeable in the art.