ISLAMIC ART, LITERATURE, AND CULTURE

THE ISLAMIC WORLD

ISLAMIC

ART, LITERATURE, AND CULTURE

EDITED BY KATHLEEN KUIPER, MANAGER, ARTS AND CULTURE

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2010 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica,

and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All

rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kathleen Kuiper: Manager, Arts and Culture

Rosen Educational Services

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Senior Editor and Project Manager

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Nicole Russo: Designer

Introduction by Janey Levy

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Islamic art, literature, and culture / edited by Kathleen Kuiper.1st ed.

p. cm.(the Islamic world)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

ISBN 978-1-61530-097-6 (eBook)

1. Civilization, Islamic. 2. Islamic literature. 3. Art, Islamic. 4. Islamic countries

Intellectual life. I. Kuiper, Kathleen.

DS36.8.I837 2010

700.88267dc22

2009037976

On the cover: Visitors tour the Sheikh Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi, United Arab

Emirates, in 2008. This mosque will be the third largest in the world when it is complete. It

contains several traditional elements of Islamic architecture and design, including ornate

wall patterns, arched columns, and a domed ceiling. Karim Sahib/AFP/Getty Images

Photo creidts: www.istockphoto.com.

CONTENTS

Chapter One:

The Varieties of Islamic Culture

Chapter Two:

Islamic Arts: Introduction and General Considerations

Chapter Three:

The Mortar of Islamic Culture

Chapter Four:

Islamic Literatures

Historical Developments:

Pre-Islamic Literature

Chapter Five:

Islamic Visual Arts

INTRODUCTION

T he Islamic world contains a rich tradition of extraordinary literature and visual arts that stretches back for centuries. At various times, these arts have influencedand been influenced byWestern literary and artistic traditions. Yet most Westerners know as little about Islamic literature and visual arts as they do about Islam itself. Popular works such as The Thousand and One Nights and vague notions of tiled mosques or lavish palaces (frequently derived from Western fiction) are often the extent of Westerners knowledge of Islamic arts. Viewing Islamic art through the lens of such works is roughly akin to trying to understand the full scope of Western literature and visual arts through popular romance novels and fairy-tale castles. The approach is neither realistic nor fair.

This unenlightened view was shattered with the tragic events of September 11, 2001, when many Americans replaced their naive notions of the exotic Orient with an outright rejection of a mostly unknown religion and all its worshippers. This attitude may be further exacerbated by the prejudice some feel toward the arts in general, that art has no connection to daily life and that it serves no useful purpose. Yet if those notions are accurate, why are the arts so intimately interwoven with human history? The truth is that the creation and appreciation of art is an integral part of what it means to be human. Tens of thousands of years agolong before writing existedpeople painted pictures on cave walls and carved small figures. Before there was writing, there was spoken language, which storytellers used to create an oral tradition that was an essential means of transmitting the fundamental principles of human society and institutions. The best among them could enthrall audiences with long, complex tales. After the invention of writing, many of these stories and poems were recorded, becoming some of the first works of literature.

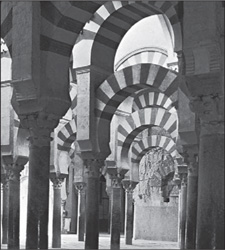

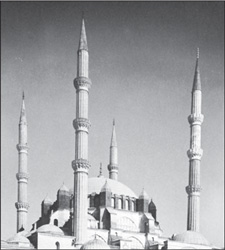

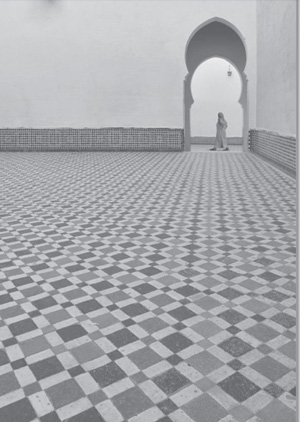

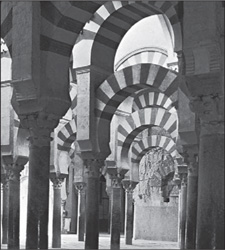

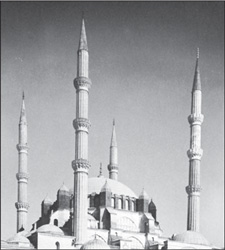

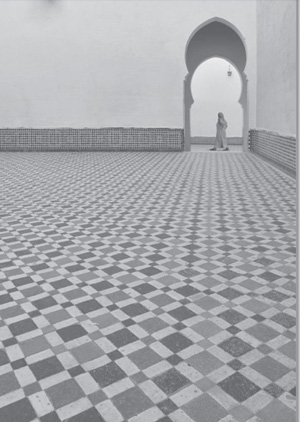

Since that time, peoples around the world have used an immense variety of materials to create innumerable artworks in a myriad of forms and styles. The effort to understand and appreciate these artworks is both a challenging and exhilarating undertaking, not only for the sheer vastness of the task, but also because art serves different purposes at different times and in different cultures. Similarity of form does not necessarily mean similarity of purpose. Ancient Egyptians, for example, placed the organs of the dead in vessels called canopic jars. Westerners today may use similarly shaped vases to hold freshly cut flowers. On the other hand, strikingly different forms may serve similar purposes. Both Quakers and Muslims, for example, needed places to worship and desired to create structures they believed would be pleasing to God, instructive to believers, and in keeping with the tenets of their faith. For Quakers, that often meant plain, simple, unadorned wooden buildings. While Muslims also often worship in spaces without ornamentation or elaboration, enormous, elaborately decorated mosques covered with colourful tiles were considered just as appropriate.

Just as the purposes of art have varied over time and among cultures, so too have the dominant modes. Literature was the preeminent art form of early Islam, and it has retained its high status over the centuries. There are several reasons for this. One is that a solid foundation existed upon which to build Islamic literature. This foundation had been laid in Arabia, Islams homeland, long before the birth of the religions founder, the Prophet Muhammad. Arabs had developed a highly sophisticated oral literary tradition. One reason for the attention lavished on verbal arts may lie in the migratory lifestyle of the Bedouin, the nomadic desert Arabs. A nomadic way of life imposes certain limits on the art forms a culture develops. Architecture, for example, does not become a major art form, and there is little motivation to create any sort of large-scale art that would be difficult if not impossible to transport easily. Verbal arts, however, are ideal for nomadic cultures.

Next page