Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kathleen Kuiper, Senior Editor, Arts and Culture

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Laura Loria

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Musicians of the Renaissance/edited by Kathleen Kuiper.1st ed.

p. cm.(The Renaissance)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-882-8 (eBook)

1. ComposersBiography. 2. Music15th centuryHistory and criticism. 3. Music16th centuryHistory and criticism. 4. Music17th centuryHistory and criticism. I. Kuiper, Kathleen.

ML390.M959 2013

780.9031dc23

2012024845

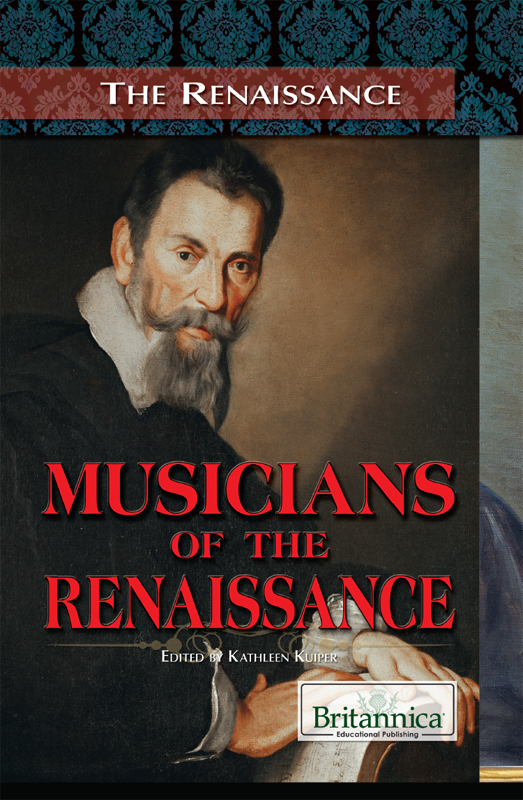

On the cover, p. iii: Portrait of Claudio Monteverdi. Imagno/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Cover (background pattern), pp. i, iii, 1, 28, 49, 67, 100, 125, 145, 147, 149 iStockphoto.com/fotozambra; p. x (sun) Hemera/Thinkstock; remaining interior graphic elements iStockphoto.com/Petr Babkin

T he Renaissance was a period of expanding knowledge. Alongside a resurgence of interest in Classical learning, new ideas regarding science, religion, and the arts flourished and spread across Europe. Humanism, with its focus on human interests and values, steered prevailing thought toward nature, the individual, and the empirical. Renaissance musicians developed a variety of musical forms, respecting traditional modes of expression even as they expanded upon them. As this book details, the musicians of the period reflected to some degree the rapidly changing world around them.

Western music was influenced by that of the eastern Mediterranean in a number of ways, including the widespread adoption of the diatonic (seven-note) scale, which replaced the prevailing church modes commonly used until then, and the use of metre as a means of dividing compositions into equal portions of time. These are basic structural elements of classical composition.

The Christian Church was a vehicle of both musical evolution and dispersion. While there were many regional styles of chant, or unison songs, sung throughout Europe as part of the traditional Western church mass, Gregorian chant was the standard. Originating in Rome under Pope Gregory I in the late 6th century, this style of unison liturgical music was adopted across Europe over the next several hundred years, and then modified by the addition of melodic lines. This polyphony, which was both simultaneous and contrapuntal, was documented in the work of 11th-century monk and musical theorist Guido dArezzo.

Hand-coloured illustration from an early 16th-century edition of Margarita philosophica by German encyclopedist Gregor Reisch. Science & Society Picture Library/Getty Images

In the 12th century, the main thrust of musical innovation shifted from Rome to Paris. At such places as Notre-Dame cathedral, music featuring multiple melodies that wove through or played against the plainsong melody was composed for liturgical, and later secular, use. Reflecting on the musical directions of his time, 14th-century French composer Philippe de Vitry wrote about the use of metre and harmony in his work Ars Nova; the label Ars Antiqua (Ancient Art) came to apply to the music of the 13th century that had foreshadowed the changes to come.

From roughly the 15th century forward, royal interests shaped the evolution of music in more or less equal proportion to those of the Roman Catholic Church. The crme de la crme of European musicians were drawn to Burgundian courts (in what is now eastern France and portions of the Low Countries), attracted by the wealth of the French aristocracy and the promise of finding work in both the secular and religious realms. Early improvisational forms can be seen in compositions of this time, with melodies centred in the top voices and lower parts played by instruments. Some nobles became traveling musicians themselves, composing and performing songs in courts across France and Italy, calling themselves troubadours. These collections of composers and performers spread innovative ideas, including four-part harmony and chord progression, throughout Europe. Still, liturgical music remained in demand, and it evolved as well.

The secularization of music encouraged the development of new vocal styles. The reinvented madrigals of 16th century Italy evolved into dramatic, five- or even six-part harmonic pieces featuring complex texts and counterpoint (independent melodies that complemented and enriched the standard melody), while simpler songs, called canzonettas and ballettos, emerged as a response to the madrigals complexity. The madrigals French counterpart was known as the chanson. Composers in Elizabethan England adopted Italian madrigals, as well as ballettos and canzonettas, and made them their own, while also championing the popular ayre that sprang up in both countries. Germany was home to the lied, a secular song performed using straightforward chord progressions. Neither the lied nor the Spanish villancico of the Iberian Peninsula could match the madrigal in its stylistic importance.

Until the 16th century, music had been primarily vocal, with instruments serving primarily to double voices or accompany dancers. By the late 1500s, pieces written specifically for instruments exploded in popularity. They included traditional dance forms, such as the pavane and courante, as well as preludes (particularly for the organ), and fugue-like forms in which instrument voices imitated a melodic line, such as the ricercari and canzoni. No longer relegated to the role of mere accompaniment, instrumentalists began to showcase their own technical skills.

The lute in particular enjoyed mass popularity. Its strings, which varied in number before settling on six in the 16th century, were plucked with the fingers. The sound carried through the sound hole, reverberating in the instruments hollow, pear-shaped body. Modified tunings produced a large assortment of variations on the lute.