AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIE

OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 67

CHOPI MUSICIANS

CHOPI MUSICIANS

Their Music, Poetry, and Instruments

HUGH TRACEY

First published in 1970 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1970 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-59877-5 (Volume 67) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48604-3 (Volume 67) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Due to modern production methods, it has not been possible to reproduce the fold-out maps within the book. Please visit www.routledge.com to view them.

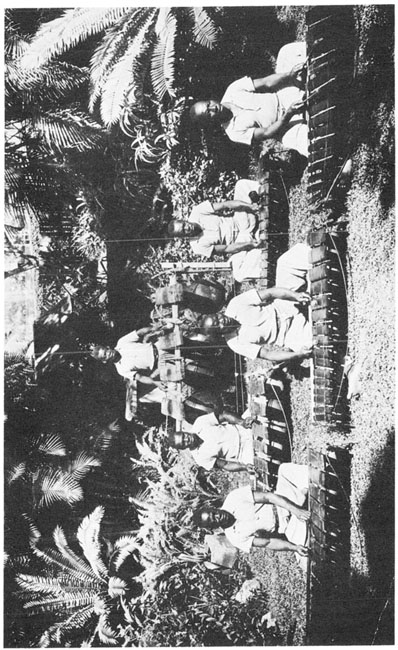

THE SIX CHOPI MUSICIANS WHO CAME TO DURBAN

Front Row(left to right) Sekelani (Cilanzane, Treble Timbila), Katini (Sage, Alto Timbila), Gomukomu (Sage, Alto Timbila)

Second Row Madoshimani (Debiinda, Bass Timbila), Bokisi (Sagge, Alto Timbila)

Behind Majanyana (Gulu, Double Bass Timbila)

CHOPI MUSICIANS

Their Music, Poetry, and

Instruments

HUGH TRACEY

Published for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

1970

CONTENTS

Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W. I

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON

CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI DAR ES SALAAM LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA

BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA

KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE HONG KONG TOKYO

SBN 19 724182 4

International African Institute 1970

First published 1948

Reprinted, with a new Introduction, 1970

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY OFFSET LITHOGRAPHY BY

BILLING AND SONS LTD., GUILDFORD AND LONDON

TO

KATINI WE NYAMOMBE and

GOMUKOMU WE SIMBI

I N the past twenty-one years since this book was first published, the Chopi have sprung from relative obscurity to world-wide recognition, largely on account of the excellence of their musicianship. The phonographic records which I have been able to publish through the International Library of African Music have established their position as one of the leading, if not the most advanced groups of instrumentalists on the African continent. They compose and perform their distinctive music and dances with undiminished enthusiasm and pleasure, in spite of the gradually changing circumstances which surround them, untouched by compromise with foreign styles and unsullied by the crescendo of popular urban music which has already undermined so much of African musical genius elsewhere.

The fertility of their craft is demonstrated by the fact that not a single composition which I recorded in their villages in the 1940s is still in current use, all the music heard today having been composed afresh in a continuous cycle of rejuvenation. The secret lies not only in their innate musicality but also in the fact that their compositions observe the strict rules of a well-founded technique and the use of an ideal minor tone scale which all Chopi musicians can follow instinctively. They base their music upon what Stravinsky has described as the resisting foundation of an established discipline which allows the greatest freedom of individuality within a clear-cut set of rules. That Chopi music still evokes exultation after at least four centuries is proof enough of its lasting merit as an effective art and recreation for their community.

It is not written music. All of it is created, performed and handed on entirely by aural contact. It is doubtful whether any Chopi musician of the present day, with two or three exceptions, would benefit from a written score. However, future composers, understanding the mechanics of their music from a scientific or measured angle, may yet rise to greater musical heights and bring the art of timbila xylophone playing to the notice of a yet wider public of African and world-wide musical intelligentsia.

There are few modifications which need be made in the text, which remains a fair portrayal of Chopi music today, and, of course, with continued acquaintance over the years new details are being added to our knowledge, particularly of the timbila makers craft. For example, only recently I learned that they prefer to cut down dead trees of the mwenje rather than the green tree, as otherwise they are liable to have difficulty in curing the wood which is then inclined to crack and have a shorter musical life.

The greatest advance will undoubtedly come when the structure of the music is sufficiently understood to be written down in some adequate notation and played by non-Chopi as well as by the perpetuators of this style.

My son Andrew, who was a small boy when I wrote this book, has begun not only to make timbila, but also to play them with the Chopi. He has rewritten the example of one of Gomukomus tunes Lavarani micanga sika timbila tamakono, published in the first edition, in the light of inside knowledge as a player rather than that of an observer only. This replaces the earlier transcription in Appendix V.

A short holiday in Lourenco Marques and the kindness of Portuguese friends there first guided my feet, or more accurately my car, a hundred and fifty miles beyond into the country of the Chopi people. That was in 1940. I was delighted and astonished at what I found in the music of two small orchestras, one at Manhica and the other beyond the Limpopo at Zandamela. I searched the libraries, perhaps too hopefully, for information upon so musical a people. I was now astonished at what I did not find. Apart from a few paragraphs here and there describing their instruments and a nibble at one or two songs, more particularly by the Junods, father and son, there was nothing whatever to reveal the extent and meaning of Chopi music, poetry, and dancing.

A short holiday in Lourenco Marques and the kindness of Portuguese friends there first guided my feet, or more accurately my car, a hundred and fifty miles beyond into the country of the Chopi people. That was in 1940. I was delighted and astonished at what I found in the music of two small orchestras, one at Manhica and the other beyond the Limpopo at Zandamela. I searched the libraries, perhaps too hopefully, for information upon so musical a people. I was now astonished at what I did not find. Apart from a few paragraphs here and there describing their instruments and a nibble at one or two songs, more particularly by the Junods, father and son, there was nothing whatever to reveal the extent and meaning of Chopi music, poetry, and dancing.

A short holiday in Lourenco Marques and the kindness of Portuguese friends there first guided my feet, or more accurately my car, a hundred and fifty miles beyond into the country of the Chopi people. That was in 1940. I was delighted and astonished at what I found in the music of two small orchestras, one at Manhica and the other beyond the Limpopo at Zandamela. I searched the libraries, perhaps too hopefully, for information upon so musical a people. I was now astonished at what I did not find. Apart from a few paragraphs here and there describing their instruments and a nibble at one or two songs, more particularly by the Junods, father and son, there was nothing whatever to reveal the extent and meaning of Chopi music, poetry, and dancing.