Contents

Guide

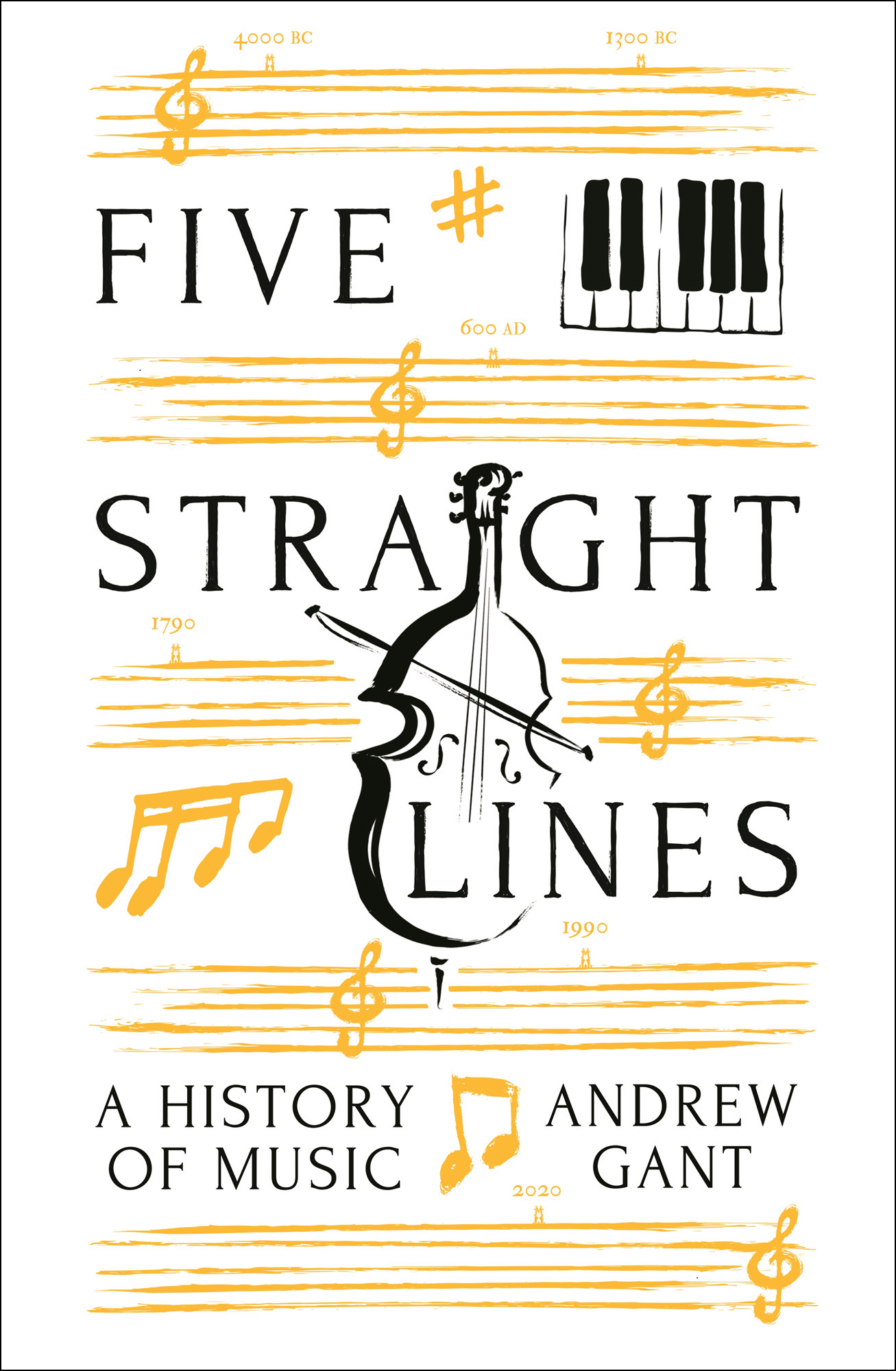

FIVE STRAIGHT LINES

ALSO BY ANDREW GANT

Christmas Carols: From Village Green to Church Choir

O Sing Unto the Lord: A History of English Church Music

Music: Ideas in Profile

FIVE STRAIGHT LINES

A H ISTORY OF M USIC

ANDREW GANT

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Andrew Gant, 2021

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd

Printed by Aquatint Ltd

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 777 7

eISBN 978 1 78283 325 3

Ive tried to read a few history books myself, and the main problem with them is this: they all assume youve read most of the other history books already. Its a closed system. Theres nowhere to start.

Jeff, in England, England by Julian Barnes

In memory of John Davey, who loved books and music

INTRODUCTION

This is a song by one of the most sublime musical geniuses of all time.

The Latin is made up. If you pronounce it with a thick Bavarian accent, it comes out as Lick my arse.

Its a joke, written by Mozart to poke fun at a friend.

There are lots of sublime geniuses in this book. But theres lots of other music, too.

Inevitably, this story leads on the great works and the great lives. But it also attempts to put those lives in context. Who were these musicians? What were they like? How did they make a living (or more often, in Mozarts case, not)? How does their music fit into the intellectual, social and technological tenor of their times? What other music did they hear? What did they sing in the pub when the concert was over? (Purcells rounds are even ruder than Mozarts.)

Music and Words

One question facing the nervous writer of a book of this kind is whether there is in fact any point in using words to describe a non-verbal creature like music. Elvis Costello famously remarked that writing about music is like dancing about architecture.

Words are all we have.

But while some musical terms have a fairly precise, even scientific definition (an octave is the distance between two sounds created by dividing the frequency of a vibrating wave into two equal parts a fact known and unchallenged since at least the age of Pythagoras), most do not. The word sonata (literally, sounded, or played, as opposed to sung) can refer to a noisy early seventeenth-century ensemble piece by the Venetian composer Giovanni Gabrieli or the knotty innards of a movement by Haydn or Brahms. A symphony could be a little snatch of strings in an anthem by Purcell, a three-movement curtain-raiser to an opera by J. C. Bach, or to Mahler the outpouring of the whole world. Spellings, and borrowings between languages, can set up some ambiguities, too: the familiar old favourite in your front room or school hall is known as a piano, but piano is simply the Italian word for quiet, borrowed as a name for the new instrument because of its ability to grade volume. The Australian composer Percy Grainger waged a one-man war on Italian terms, refusing to use even the humble Italian-derived violin, preferring the more Anglo-Saxon fiddle (to the extent of calling the cello the bass fiddle, and the viola, rather pleasingly, the middle fiddle).

Words move through time. The word just used to describe Grainger is composer. Usage of that word has come to imply inspired thought, spontaneous utterance: making things up. In fact, its etymology also contains ideas of assembly, of putting things together, of placing working parts next to each other. Its about artifice as well as art, engineering as much as hearing secret harmonies. Stravinsky once told a French border guard he was an inventor of music rather than a composer.

The English language, that rich, shifting, many-layered creature, has other words for people who make things. Someone who works with words is a wordsmith, like a blacksmith. The person who makes plays is a playwright, like a wheelwright or a shipwright. Could the composer who fashions sounds into shapes be a notesmith, or a note-wright? Not just a dreamer of dreams, but a maker of things.

Names shift in time, too. The sixteenth-century English composers William Byrd and Thomas Tallis were spelt Bird, Birde, Byrde, Byrdd and Talles, Talliss, Talless, Taliss, and other variants, in contemporary documents. Mozart, like any well-educated eighteenth-century polyglot, translated his name depending on where he was, turning his baptismal Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus into Gottlieb, Amadeus and hybrids like Wolfgang Amad Mozart. Other names changed through travel, politics and local usage: Roland de Lassus became Orlando di Lasso, Israel Beilin became Irving Berlin, Fritz Delius became Frederick, Gustav von Holst lost his von and Schnberg his umlaut. Some musicians are known after the place they came from (Palestrina, Viadana, Gilles de Bins dit Binchois); others by nicknames or stage names (Heinrich In Praise of Women Frauenlob, William Count Basie, Jacob Clemens Not the Father non Papa, which seems to be an obscure Renaissance in-joke). Some names still havent quite settled into an accepted usage: scholars tussle politely over whether the celebrated fifteenth-century English polymath John Dunstable was actually Dunstaple. Suffice to say that the composer himself wouldnt have given a quilisma one way or the other.

There is, inevitably, technical language in this account. This raises the question of how we write about music. We can do this:

the first subject is presented in the minor tonality before being developed through modal shift, retrograde, and fully worked-out triple invertible counterpoint.

Or we can do this:

I took the theme for a walk, then in the middle I changed it to major and came up with a very sprightly little tune, but in the same tempo, then I played the theme again, but this time ass-backwards; in the end, I wondered whether I couldnt use this merry little thing as a theme for the fugue? Well, I didnt stop to inquire, I just went ahead and did it, it fit so well as if it had been measured by [my tailor].

The first is an amalgam of the kind of instruction handed down by harmony and counterpoint tutors since time immemorial. The second is by Mozart.

Is one or the other what the writer and pianist Charles Rosen loftily described as a failure of critical decorum?

Actually, both are indispensable and unavoidable. As the lyricist Sammy Cahn said, You cant have one without the other. The trick is to get the balance right.

The question of how much knowledge to assume is, of course, a matter of judgement. I hope I have flattered my reader just enough. In any event, the cautious author can take some comfort from the fact that this is not a new problem. In the preface to his admirable