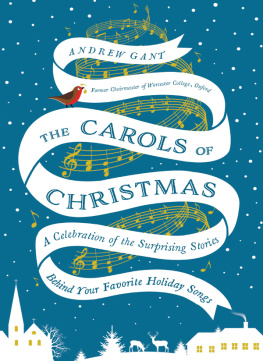

2015 by Andrew Gant

Music Arrangements copyright Andrew Gant, 2014

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc.

Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

I Wonder As I Wander by John Jacob Niles. Copyright 1934 (Renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP). International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. This Arrangement Copyright 2015 G. Schirmer. Used by Permission of Chester Music Limited trading as G. Schirmer.

A version of this text was published in 2014 by Profile Books Ltd under the title Christmas Carols.

ISBN: 978-0-7180-3153-4 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944228

ISBN: 978-0-7180-3152-7

15 16 17 18 19 RRD 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Kathy

Contents

E nglish Christmas carols are a hodgepodge of nationalities and influences, like Americans themselves. Perhaps thats why they are so popular. They have the power to summon up a special kind of midwinter mood, like the aroma of mince pies and mulled wine and the twinkle of lights on a tree. Its a kind of magic.

How did they get that magic? Most of these songs were not composed as Christmas carols. Many were not composed at all. Almost all did not begin life with the words they have now. Some didnt have words at all. Several evolved from folk songs; some are evolving still. One much-loved carol started out as a song about a delinquent farm-boy and a couple of dead cows. Many of the most English carols have at least one ancestor in another country, in the mountains of Austria or nineteenth-century America or a Pyrenean hillside; in Lutheran psalters, handsome volumes of illuminated plainsong or sturdy hymnbooks from Finland, first opened by the flickering light of a fire in some stone hall one dark evening, deep in the sixteenth century.

The origins of the word carol are almost as murky as the history of some of the tunes themselves. Most European languages, living and dead, have been quoted as the source of the word, though most writers agree that there is a dash of French in there somewhere.

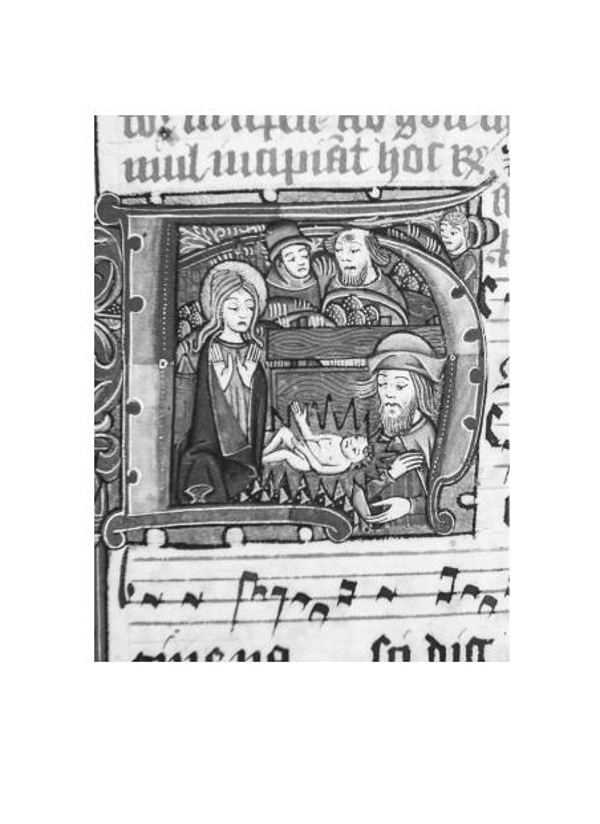

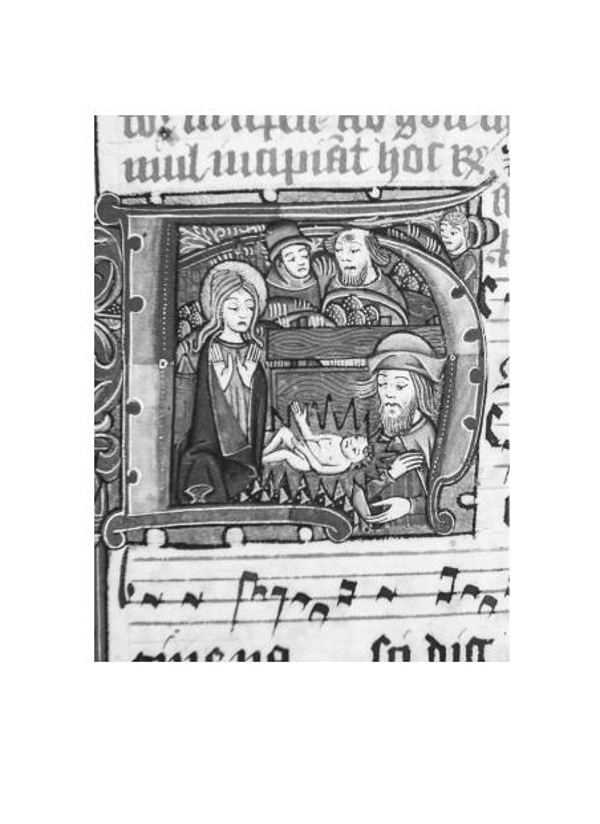

In the beginning, a carol was a celebratory song, with dancing. There is no exclusive connection to Christmas. Music is in the traditional stanza and burden (or verse and refrain) format. It certainly has nothing to do with church. In about 1400, the gory tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, as translated by J. R. R. Tolkien, tells us: The king lay at Camelot at Christmas-tide with many a lovely lord... to the court they came at carols to play... they danced and danced on, and dearly they carolled.

Choirs sang church music. Everyone else sang carols. Tolkiens version of Sir Gawain draws the distinction between songs of delight, such as canticles of Christmas and carol-dances.

Folk carols on Christian themes were sung in the field and the graveyard, and on semi-magical processions round the parish. Their texts often cover the entire Christian worldview, from creation to resurrection. Today, we tend to just snip out the bits we want at Christmas, for example, Tomorrow shall be my dancing day and The cherry-tree carol, which was not how our medieval forebears used these songs at all.

Fifteenth-century English carols began to take on some of the sophistication of the church composer. The texts are macaronic, freely dropping Latin words and phrases into an English lyric:

There is no rose of such vertu

As is the rose that bare Jesu.

Res Miranda.

The music is in the ubiquitous verse-and-refrain format.

By the sixteenth century, the word carol could find itself loosely applied to any song with a seasonal connection, still definitely not just Christmas. An ancient and mysterious folk song appeared under the title Corpus Christi Carol in 1504. Court composer William Cornysh was paid the handsome sum of 20 for setting of a Carrall upon Xmas day at around the same time as Wynkyn de Worde included the entirely secular Carol of hunting in the collection that he (rather confusingly) called Christmasse carolles in 1521. One of William Byrds consort songs from around the 1580s, designed to be sung at home, has the subtitle A Caroll for New-Yeares Day. A text sung in church at Christmas could also be a carol, whether the words make any reference to the nativity or not. A 1630 publication refers to Certain of Davids Psalmes intended for Christmas Carolls fitted to the most common but solempne Tunes. These Carolls are just the psalms of the day. Neither words nor music have any seasonal content.

Protestants wanted to grab the best tunes back from the devil and the pub. During the Reformation, secular songs and well-known chorales started to be used in worship. Compilers of tunes for psalm singing, hugely influential and popular, put them in their psalters. Alongside this went a passion for education. School songbooks sprang up everywhere. One such book, Piae Cantiones ecclesiasticae velerum episcoporum, is the source of a large number of our best-known carols. In France, dancing-masters and chefs du choeur started noting down little rustic Nols and incorporating them into published collections, for teaching, playing, dancing, and singing, and sometimes adding new words. All feed into the tradition we have today.

In the mid-seventeenth century a more extreme brand of Protestantism took hold in England, with its stern disapproval of any kind of levity in church, or indeed anywhere else. The Puritans, famously, banned Christmas. As always, though, we need to see this in context. Puritans banned a lot of things. Christmas was not the mad, musical midwinter party we have come to know since. It went as part of a general assault on saints days and elaborate ritual in church practice as a whole, and as part of a rather arcane dispute about which took precedence when a liturgical fast fell on the same day as Christmas. The jollity, of course, came back in a great whirl of enthusiasm at the Restoration in 1660. Carols, like life, were mainly an excuse for having fun. Songs about drinking, wassailing, drinking, eating, dancing, and drinking were especially popular.

The more measured Protestantism of the very last StuartsWilliam, Mary, and Annemade its own distinctive contribution. The beginnings of congregational hymn singing in the eighteenth century give us familiar carols like While Shepherds Watched, still closely based on the old style of metrical psalm singing. These words have been sung to all sorts of different tunes, each one reflecting the social and religious preoccupations of the singers.

The Wesleys and Watts gave their followers lengthy devotions to sing on the dusty road, which have been absorbed into the popular consciousness. Wattss lovely Cradle Song turns up, suitably distorted by the Chinese whispers of an oral tradition, as the words of an English folk song. Parish churches, with their distinctive bands of instrumentalists and West Gallery choirs, mixed fashionable metropolitan musical style with a love of hymn singing and their own intensely local traditions to create something sturdy, uniquely English, and full of character.

Next page