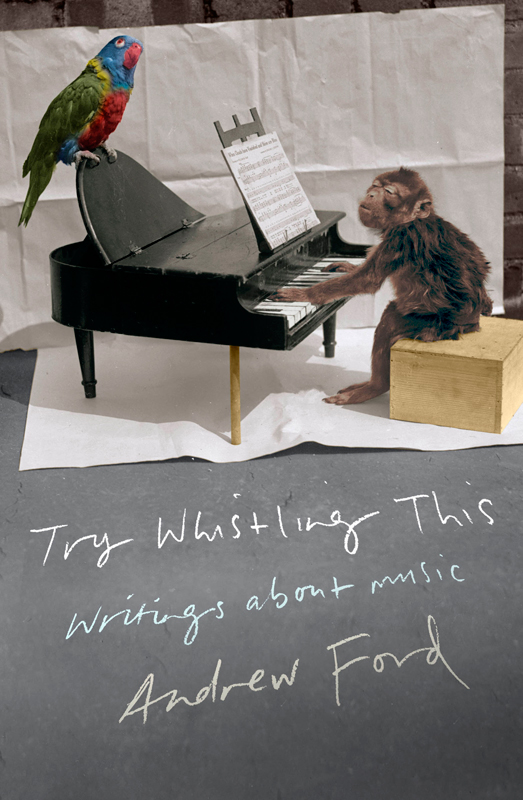

TRY WHISTLING THIS

WRITINGS ABOUT MUSIC

Andrew Ford

Copyright

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood Vic 3066 Australia

email: enquiries@blackincbooks.com

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright Andrew Ford 2012.

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

ISBN for eBook edition: 9781921870682

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry (for print edition):

Ford, Andrew, 1957

Try whistling this : writings on music / Andrew Ford.

ISBN for print edition: 9781863955713 (pbk.)

Includes bibliographical references.

Music--History and criticism.

780.9

Book design by Peter Long

Contents

for Richard Gill

Introduction

What you are holding is, I suppose, a book of music criticism. Do you sense the reluctance with which I use the term? Can you detect my unease at labelling myself a critic? Would it help if I said that this is a book of critical writing? Probably not.

In the introduction to his own collection of essays, How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken , the literary critic Daniel Mendelsohn suggests that the popular uses of critic (as in Everyones a critic!) and critical (Dont be so critical!) lie behind our societys poor opinion of the critics trade. When it comes to music criticism, however, it gets worse: tensions escalate. We have all had the experience of attending a concert we have loved or hated and next day reading a review that points out we were wrong to have had that response. The critic was disappointed by things we never even noticed, and cringed at the very aspect of the performance that most impressed us; or the critic found profundity and eternal values in what we thought was trash. We are appalled at the travesty and write letters of complaint to the newspaper that printed the review. One famous example of this phenomenon, discussed in the following pages, was the open antagonism displayed to most of the Western worlds classical music critics when they pointed out that, in terms of the classical tradition, David Helfgotts piano playing wasnt terribly good. Capacity audiences across America, Europe and Australia had loved Helfgotts recitals, so what did critics know?

With music it is personal and more so today than ever, for in the age of the iPod we own our music and identify with it. The playlist defines us, just as our clothes do. But there is a difference: the purpose of the songs on our iPods is not to tell others who we are, but to tell ourselves. We buy the music (or steal it) and then carry it around with us as a tortoise carries its home. If someone suggests that our music isnt as good as something else something that isnt in our iPod, something, perhaps, we have never even heard of we are quickly defensive. It is a clich to say it, but when it comes to music, most of us know what we like and like what we know. And on Facebook, apparently, that is enough. Thumbs up.

But liking should never be enough, certainly not for a critic. Indeed, it is such a subjective matter that it is scarcely worth discussing. Why should your likes concern me? Why should my dislikes be of the least interest to you? If a music critic cannot get beyond this level of commentary and the worst of them seldom do they deserve all the opprobrium we can heap upon them.

The critics job is to listen harder than anyone else and offer context, from which it becomes possible for the critic or reader to assess the worth of the music. It is not sufficient to announce that a work is good or bad, successful or unsuccessful; we have to be told the reasons and these come from context. The critic must therefore have a wide experience of all music, and especially todays music, because that is where the context is to be found there is no point in reviewing a concert from a nineteenth-century perspective. It is not that we must agree with critics on the contrary, we should be prepared to argue but we ought to be able to trust them to be musical (and in classical music to be musically literate), to have their facts straight, to have background knowledge and to be able to make illuminating connections all of which is context; they should also avoid clichs and try to be fair. The last bit is tricky, but what I mean is that they should, as far as possible, leave any agenda at the box office. All good criticism begins from the point of view of the music. The critic must ask what it is the composer and/or performer is aiming for, and then whether on its own terms the music has succeeded. It is also permissible to enquire whether the original aim was worthy (which involves context again), but this should not be the critics starting point.

All that said, the truth is I am not a critic, or not really. Most days of the week I am a composer, but like nearly all composers I supplement my income with other work. Some of us perform, some teach, some work in arts administration, and some write and talk about music. Throughout history, much of the best writing about music has been by composers. I am thinking of Berlioz, Schumann, Debussy, Copland, Carter, Tippett, Virgil Thomson and Peggy Glanville-Hicks, among others. It reassures me to name them: if Schumann and Debussy did it, criticism cannot be a dishonourable pastime for a composer, however much other composers may disparage the business, and however much I do so myself when I cop a nasty review.

In fact, I have only written one concert review in my life (as an unpaid favour). My reviewing is more long-distance, dealing with books and recordings. Writing about concerts in newspapers might be the frontline of music criticism, but my long-distance writing is nevertheless critical, even when it isnt passing judgement. And it attempts to provide context, avoid clichs and be fair.

So why do I resist the label critic? I suppose it is because I am a composer, and because I would like these pages to be read with that in mind. It isnt that composing necessarily gives me special insights, more that it is my sole justification for writing about other peoples music. Were I not in the same boat, I dont think Id have the nerve. I claim the right to discuss and comment on and judge the creativity of others because I put my music out there for similar scrutiny. Of course, I dont say all music critics should themselves be composers there are some very good ones who are not but for me, and for my peace of mind, it is important that I know the work that goes into writing music, and the frustrations, and also know how it feels, in Stephen Sondheims words, to make a hat / Where there never was a hat.

The present collection consists of a few reviews, rather more essays, a couple of lectures and the scripts of my radio series Music and Fashion . As far as the essays and reviews are concerned, I am fortunate that my editors usually allow me to write about the things I want to write about, and to that extent I notice that some of the subjects in this book are the same as they were in my earlier collection, Undue Noise . Here again are Dylan and Cole Porter, Vaughan Williams, Tippett and Britten, Mozart, Shostakovich and Elliott Carter. And favourite themes are revisited you might call them obsessions such as the intersection of words and music, the necessity of modernism and its concomitant dangers, and the fundamental importance, in music and in life, of listening. In each case, I have returned to my original writing and re-edited it, changing as little as possible. Mostly I have been on the hunt for repetitions, though a few remain.