Contents

Guide

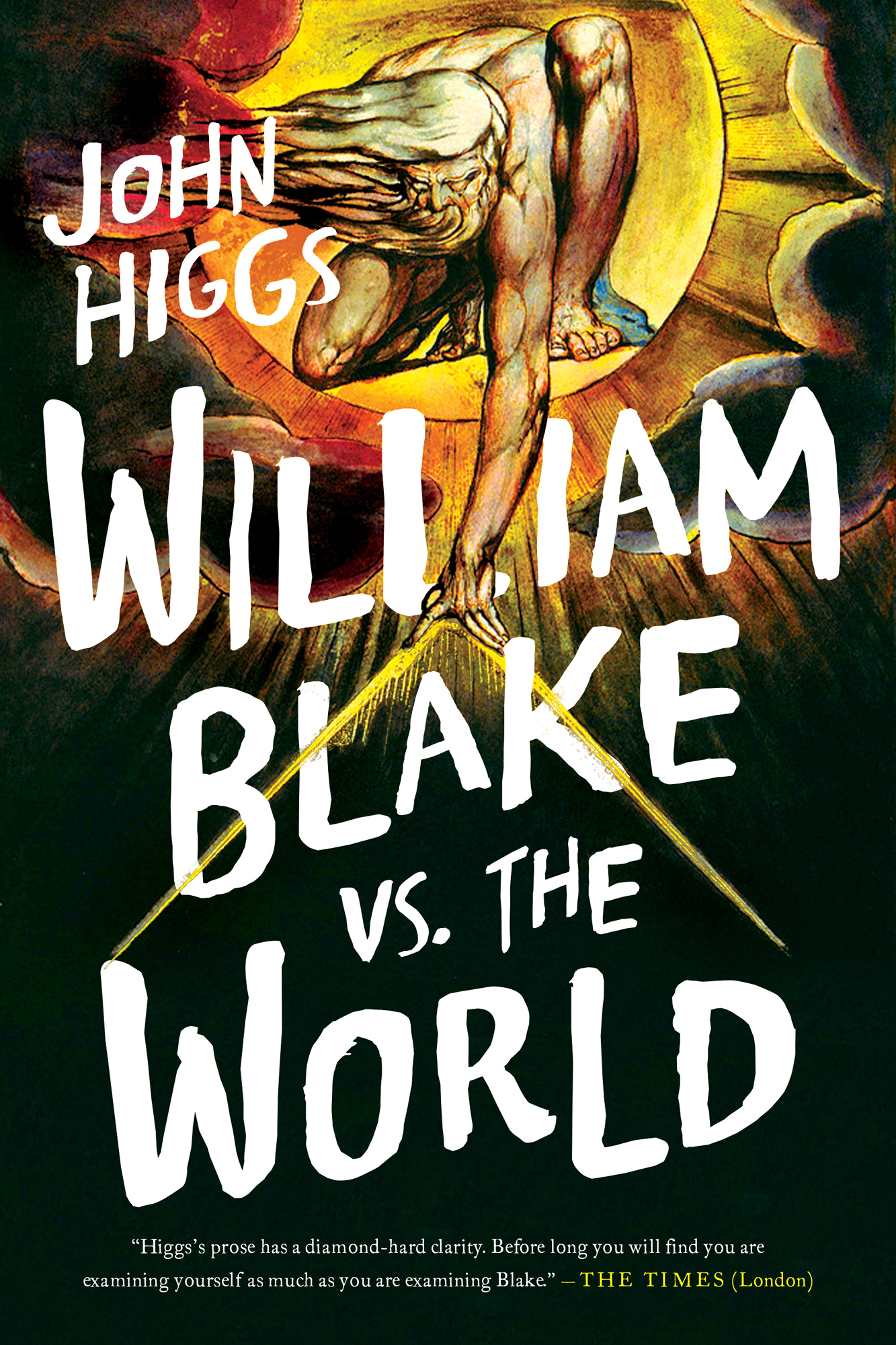

John Higgs

William Blake vs. the World

Higgss prose has a diamond-hard clarity. Before long you will find you are examining yourself as much as you are examining Blake.The Times (London)

There is certainly another world, but it is in this one

Paul luard

A NOTE ON QUOTATIONS

William Blake did not attend school as a child and the home-learnt nature of his writing is often apparent. Historically, this has bugged academics a great deal. Blake scholars have typically had a rigorous formal education and been taught to attach high importance to grammar, punctuation and spelling. For them, the urge to tidy up Blakes text and to fix mistakes here and there, to make things easier for the reader, has been almost irresistible.

The problem with this was knowing when to stop. Scholars began by just adding a few harmless missing commas. Yet the temptation to keep polishing remained strong, and before long they added their own rhythms to the text. Different academics made different fixes, and in time Blakes work began to vary from source to source.

The current academic attitude is that its best to leave the whole thing alone, and that we should learn to live with Blakes punctuation and grammar. This is the approach I also use. The majority of quotations from his works are taken from the 1988 revised edition of The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake, rather than earlier, politely amended sources.

This choice was not made just for reasons of academic purity. It was also done out of a love of the writing quirks displayed. What type of person doesnt love stray capitals, random punctuation and a giddy abundance of ampersands? Like the fingerprints visible in the clay of early Aardman animations, or the warts-and-all one-take rawness of early rock n roll recordings, a writers idiosyncrasies and mistakes humanise their work. They reveal their writing to be the painstakingly built creation of an imperfect soul trying to construct something extraordinary. Blakes works were so visionary that the presence of the fingerprints of a flawed human creator in the text itself can only add to them.

This rule only applies to the words of Blake, of course. The reader is entirely within their rights to view any typos by the author as unforgivable and unprofessional, and as a source of eternal shame.

1. THE END OF A GOLDEN STRING

On 10 December 1825, the fifty-year-old English lawyer Henry Crabb Robinson attended a dinner at the home of his friend, the London businessman Charles Aders. Eliza, Aderss wife, was a painter and printmaker, and she had invited a few artist and engraver friends to the party. Over the course of the evening Robinson became increasingly fascinated by one of the guests an elderly, relatively unknown poet and painter by the name of William Blake, whose conversation casually roamed from the polite and mundane to the beatific and fantastic.

Blake was short, pale and a little overweight, with the accent of a lifelong Londoner. He was dressed in old-fashioned, threadbare clothes and his grey trousers were shiny at the front through wear. His large, strong eyes didnt seem to fit with his soft, round face. Robinson noted in his diary that he had an expression of great sweetness, but bordering on weakness except when his features are animated by expression, and then he has an air of inspiration about him.

For all his wild notions and heretical statements, Blake was pleasant company and easy to like. The aggressive and hectoring voice of his writings was not the Blake those who met him recall. Many years later, another guest at that party, Maria Denman, remarked that, One remembers even in age the kindness of such a man.

What made Blake so fascinating was the casual way in which he talked about his relationship with the spirit world. Blake, Robinson wrote, spoke of his paintings as being what he had seen in his visions And when he said my visions it was in the ordinary unemphatic tone in which we speak of trivial matters that everyone understands and cares nothing about. Blake peppered his conversation with remarks about his relationship with various angels, the nature of the devil, and his visionary meetings with historical figures such as Socrates, Milton and Jesus Christ. Somehow, he did this in a way that people found endearing rather than disturbing. As Robinson wrote, There is a natural sweetness and gentility about Blake which are delightful. And when he is not referring to his Visions he talks sensibly and acutely.

Robinson walked home with Blake that night and was so struck by the conversation that he spent the evening transcribing as much of it as he could remember. The two men became friends, and Robinsons diary an invaluable record of how Blake acted and thought during the last two years of his life. Shall I call him Artist or Genius or Mystic or Madman? Robinson mused that first night. He spent the rest of their relationship attempting to come up with a definite answer. Probably he is all, was the best he could find. It is a question that has puzzled many who have encountered Blakes work over the following two centuries.

Through his attempts to understand his new friend, Robinson only became more confused. Some of Blakes declarations appeared to be foolish nonsense. When they first met, Blake told him that he did not believe that the world was round, and that he believed it to be quite flat. Robinson attempted to get Blake to justify this outrageous claim, but the group were called to dinner at that moment and the thread of the conversation was lost. While some of Blakes opinions appeared obviously wrong, others were simply baffling. When Robinson asked him about the divinity of Jesus, Blake replied that, He is the only God. And so am I and so are you. How could Robinson even begin to interpret an answer like that? If there was any sense to be found, it was quite outside mainstream nineteenth-century theology.

Yet Robinson couldnt bring himself to dismiss Blake as a simple madman, nor could he shake the suspicion that there was something important and vital about his worldview, even if it was frustratingly obscure. As he later wrote, It is strange that I, who have no imagination, nor any power beyond that of a logical understanding, should yet have great respect for the mystics.

A week after the party, Robinson made his first visit to Blakes home at Fountain Court in the Strand, where he lived with his wife, Catherine. The building itself has long since gone, but it was roughly where the Savoy hotel now stands. Robinson was unprepared for the level of poverty in which the couple were living. I found him in a small room, which seems to be both a working room and a bed room, he wrote. Nothing could exceed the squalid air both of the apartment & his dress, but in spite of dirt I might say filth an air of natural gentility is diffused over him.

This was the second of the two rooms that the Blakes rented on the first floor of the building. The first was a wood-panelled reception room, which doubled as an unofficial gallery for Blakes drawings and paintings. The second, at the rear, was reserved for everything else. In one corner was the bed, and in the other was the fire on which Catherine Blake cooked. There was one table for meals, and another on which Blake worked. From here he looked out of the southern-facing window, where a glimpse of the Thames could be seen between the buildings and streets that ran down to the river. This sliver of water would often catch the sun and appear golden. Behind it, the Surrey Hills stretched into the distance. For all the evident poverty, visitors spoke of the rooms as enchanted. As one later recalled, There was a strange expansion and sensation of Freedom in those two rooms very seldom felt elsewhere.