Contents

Where there is no vision, the people perish.

Proverbs 29:18

Were all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the kerb.

Joss Cope

At some point in the 1980s we gave up on the future. Before then, we imagined wonderful days to come, free from disease, work and want. Thanks to television series like Star Trek or events like the 1939 Futurama World Fair, this shining vision became so ingrained in our culture that it could be spoofed by childrens cartoons such as The Jetsons or Futurama .

At the Futurama World Fair, a time capsule was buried 50 feet under New Yorks Flushing Meadows. It contained items such as seeds, a pack of cigarettes, a department store catalogue on microfilm and a message from Albert Einstein. This capsule was designed to be opened in the year 6939. When we thought about the future in the 1930s, we assumed that our civilisation would be alive and thriving in 5,000 years time.

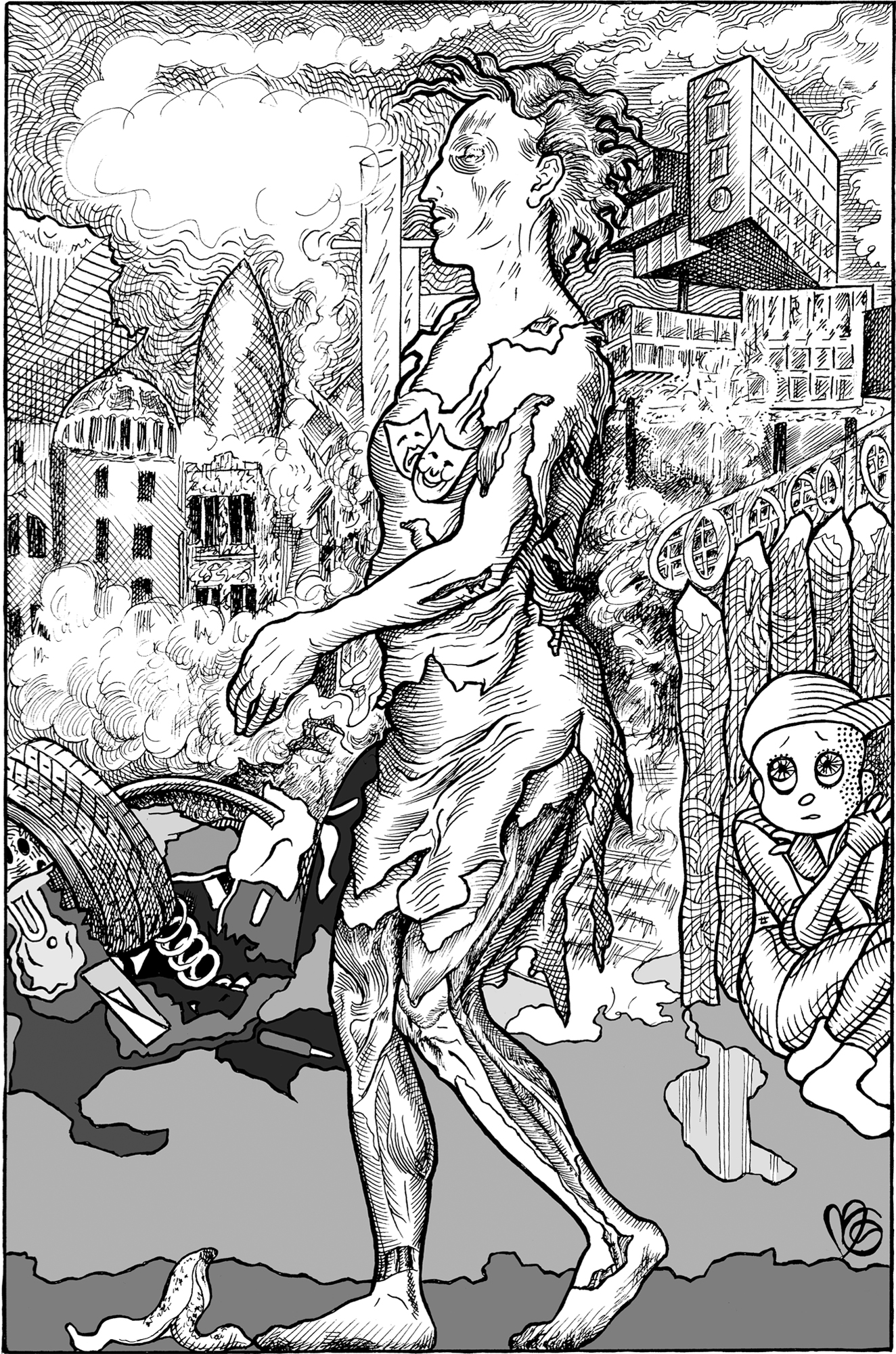

Since then, our vision of the future has changed. When we look ahead now, we tell dystopian stories of environmental collapse, zombie plagues and the end of civilisation. Hollywood, TV and Young Adult novels all sing the same tune: it is downhill from here. If it is true that we must imagine the future before we can build it, then this is deeply worrying.

It is sobering to think back over all the films youve seen in the past few decades, and try to find a vision of the future that youd want to live in. As far as I can tell, the last attempt at a utopian future in a mainstream Hollywood film was the 1989 comedy Bill and Teds Excellent Adventure . This was a future described as being fairly similar to now, but with better waterslides. By 1989, that was the best future our imagination could offer.

When the post-apocalyptic Australian film Mad Max 2 was produced in 1981, it was necessary to explain to the audience why civilisation had collapsed. Text at the start of the film explained how, in the near future, the world would run out of oil and this would lead to the dystopia depicted in the story that followed. Now, it is no longer necessary for writers and filmmakers to explain the post-collapse worlds they explore. There is no explanation about what went wrong in Cormac McCarthys hope-killing 2006 novel The Road , nor is there any explanation for the existence of zombies in the long-running comic book series The Walking Dead . Audiences are primed to accept this narrative shorthand because dystopia, we understand, is what our future is going to be. P. D. Jamess 1992 novel The Children of Men describes a disintegrating British society in the year 2021 which is devoid of hope and purpose and increasingly bleak and violent. The reason given for this is unexplained mass sterility which caused children to stop being born in the mid-1990s. Whats disturbing about the book now is that it feels like we are heading towards a similar society, and we dont need the plot device of mass sterility to get us there.

Even dystopias that were intended as jokes have come to seem horribly prophetic. In the same year as Bill and Ted , the film Back to the Future II took us forward 30 years and showed us a broken-down future which was violent, divided and ruled over by a moronic billionaire inspired by Donald Trump. As the director Robert Zemeckis said, rather than trying to make a scientifically sound prediction that we were probably going to get wrong anyway, we figured, lets just make it funny. Thirty years later, the joke has become a little hollow. As the American writer Adam Sternbergh has noted, the biggest problem with imagining dystopia seems to be coming up with some future world thats worse than whats happening right now.

If we judge by the stories were fed by film and television, then our current civilisation can feel like a crime novel with the last page ripped out. We dont know exactly the identity of the murderer, but we do know that the story is about to come to an end. Perhaps a new antibiotic-resistant disease will erupt into a global pandemic and wipe us from the face of the Earth. Maybe a massive solar flare will destroy our electronic equipment and send us back to the Stone Age. There could be a killer robot uprising just around the corner, or perhaps our old favourite, nuclear war, will make a comeback. Even if we avoid all these possibilities, economic collapse caused by environmental devastation, climate change and the collapse of biodiversity is still getting closer, no matter how hard we try not to think about it.

In our current functioning society, an ATM will give me bank-notes that I can then use in the local supermarket, which has shelves piled high with whatever I need. As long as this situation continues, I know that civilisation is still working. We had a narrow escape during the financial crisis of 2008, when Britain was only two hours away from the ATMs being turned off. The switching-off of ATMs is, I suspect, a more likely scenario for the end than alien spaceships filling the sky or mushroom clouds over London. Visa card chip-and-pin payments failed across Europe for a few hours in June 2018, and over 5 million attempts to pay for everyday necessities such as petrol and groceries failed. Although this outage only affected Visa, it still demonstrated how reliant we have become on an electronic financial system, and how much we have moved away from physical money.

Perhaps a level in a videogame is a more apt metaphor for our current world than the end of a book. When something comes to an end in a story, it does so in a way that is meaningful in terms of the larger narrative. In a videogame, you keep going for as long as you can, but eventually you make one slip and then its all over. Theres no purpose or logic to such an end. It can come at any time. It does not matter how long youve been playing, or how brilliantly youve overcome the many problems encountered in the past. Any point could be Game Over, and there are no continues or extra lives.

I am old enough to remember when we still had a future. When I was growing up in the 1970s, the idea that society was progressing, and that life would get better, was still a part of mainstream culture. Politically, the 1970s were a time of economic stagnation, strikes and upheaval, but we could still imagine that these were temporary frustrations and that an exciting future remained just over the horizon. America landed on the moon six times between 1969 and 1972, so a future in outer space appeared to have begun. Miraculous-sounding machines called computers had the potential to supercharge our technology. Glam rock and musicians such as David Bowie suggested our golden future could be a dazzling time of freedom and liberation. The idea of constant progress and improvement had been the dominant Western narrative for centuries, embedded in everything from the Age of Enlightenment to the American Dream. When the Sex Pistols emerged like harbingers of an unwelcome nightmare and announced that we had no future, that was really shocking.

In 2015, Disney produced a big-budget family adventure film about our lost dream of the future. As the director, Brad Bird, explained, When [co-writer Damon Lindelof and I] were little, people had a very positive idea about the future, even though there were bad things going on in the world. Even the 1964 Worlds Fair happened during the Cold War. But there was a sense we could overcome them. And yet now we act like were passengers on a bus with no say in where its going, with no realization that we collectively write the future every day and can make it so much better than it otherwise would be.