About the Author:

Kengo Kuma is one of Japans leading architects and a professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Tokyo. He is widely known as a prolific writer and philosopher and has designed many buildings in Japan and around the world, notably the Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo, LVMH Groups Japan headquarters, Besanon Art Centre in France and the V&A Dundee in Scotland. Most recently, he designed the stadium for the Tokyo Olympics in 2021.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Kengo Kuma: Complete Works

Kenneth Frampton and Kengo Kuma

The Elements of Modern Architecture

Antony Radford, Amit Srivastava and Selen Morko

David Adjaye Works: Houses, Pavilions, Installations, Buildings, 19952007

Peter Allison

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

CONTENTS

by Kengo Kuma

Kenz Tange, 1964

Kengo Kuma, 2003

Kengo Kuma, 2019

Kengo Kuma, 2009

Kengo Kuma, 2014

Kengo Kuma, 2020

Kengo Kuma, 2007

Kengo Kuma, 2012

Kengo Kuma, 2013

Kengo Kuma, ongoing

Kengo Kuma, ongoing

Kengo Kuma, 2010

Kengo Kuma, 2014

Kengo Kuma, 2012

Kengo Kuma, 2014

I was born in an area between Tokyo and Yokohama that did not belong to either city. Ever since I was a small child, I would ride the Toyoko line, which connects these two great metropolises, when I was out and about, as an integral part of my daily life.

I became a border person, as defined by the sociologist and philosopher Max Weber, viewing Tokyo from an outsiders perspective. Observing the city while walking around its streets enabled me to discover a wide variety of locations, cultures and people, and that Tokyo is a collection of small villages, rather than one big city.

When designing the National Stadium (that would be in keeping with the surrounding neighbourhoods of Aoyama, Sendagaya and Gaien, rather than something that was representative of Japan as a whole. We achieved this by drilling down into the essence of these different villages. When I design a building, in any city, I believe that the world is a collection of villages, instead of a group of nations.

Built as the swimming and diving venue for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, designed by Kenz Tange (19132005), became a symbol of the event. By hosting the Olympic Games, Japan was showing the world it had fully recovered from the destruction it had sustained during the war.

Other projects completed in time for the Games include the Tkaid Shinkansen, the worlds fastest railway at the time, and the Shuto Expressway, a network of motorways built in the sky above Tokyo, which featured in the Soviet sci-fi film Solaris (1972). Another building, the Komazawa Gymnasium, a stunning concrete tower designed by Yoshinobu Ashihara (19182003), was inspired by pagoda design and hosted the wrestling events.

The year 1964 also marked the peak of Japans rapid economic development, the result of a deliberate process of industrialization undertaken with unusual speed. This exultant national mood was translated splendidly into architectural form by Tange, who led the modernist movement in postwar Japan. Known as the worlds Tange, he designed buildings in over thirty countries, and was seen as having an uncanny ability to accurately predict and interpret the spirit of the age.

Anticipating that the height of buildings would increase across Japan, Tange proposed a vertically orientated design for the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, with two concrete towers and a roof suspended between them. Japanese cities at the time were made up entirely of wooden structures, one or two storeys high, and this striking design stood out dramatically. (Japans first skyscraper, the Kasumigaseki Building, wasnt completed until four years later, in 1968.)

The gymnasiums structure was supported by a system used primarily in civil-engineering projects like suspension bridges. Tanges daring design earned widespread praise, and seemed to be showing the world that Japanese technology had caught up with that of the West. The beautiful sweeping curve of the roof has been compared to the gentle curves of the Golden Hall (kond) of Tshdai-ji, the famous eighth-century temple at Nara, while the supporting pillars appear to be influenced by the chigi (forked roof finials) of buildings such as the Ise Grand Shrine in Mie Prefecture. Tanges great talent lay in combining traditional Japanese aesthetics with cutting-edge architectural techniques.

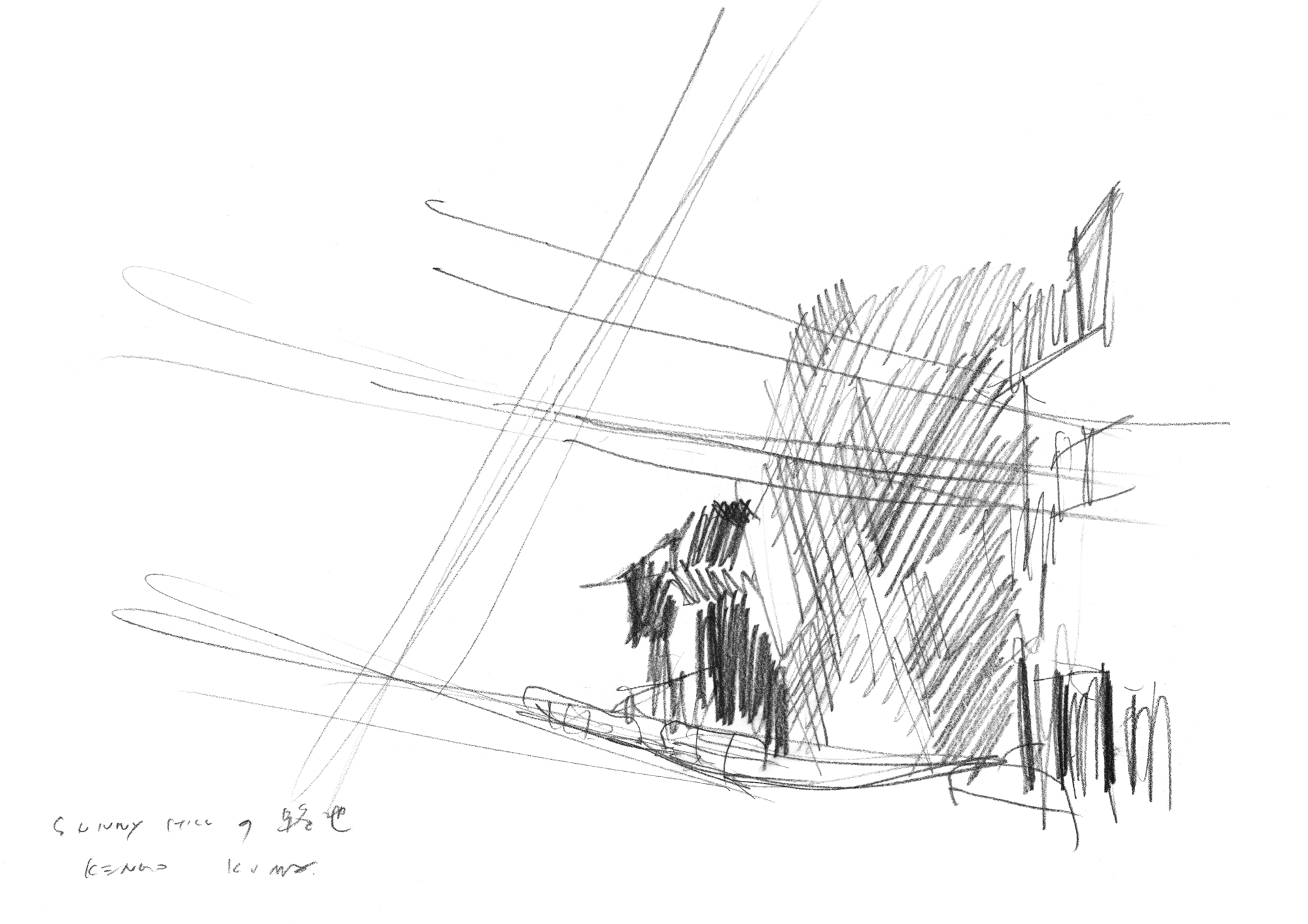

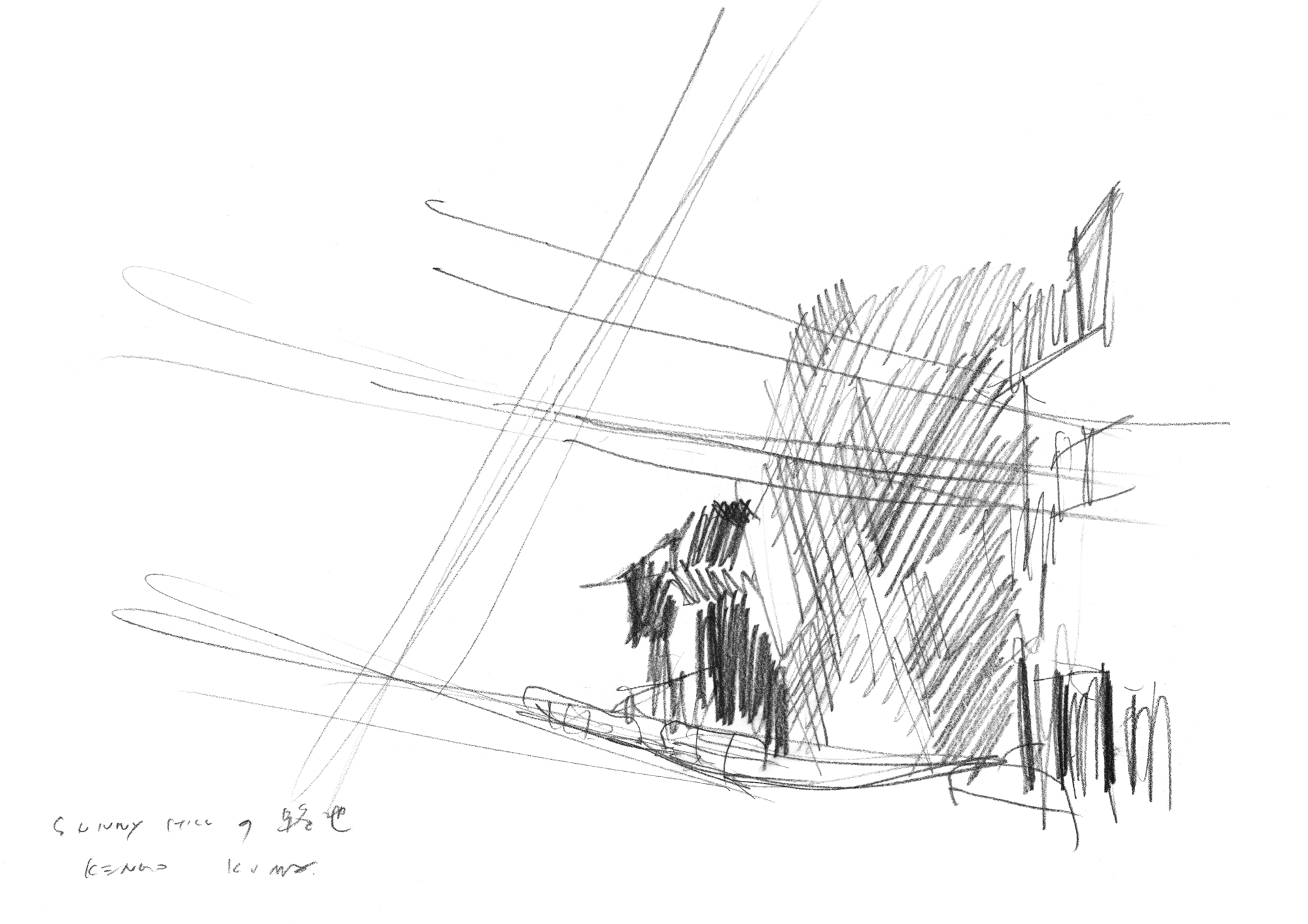

Our design for the National Stadium (), the centrepiece for the second Tokyo Olympics in 2021, was also very inspired by traditional Japanese architecture. But while Tange aspired to verticality, we looked to horizontality, believing that pre-1964 Tokyo, with its low wooden silhouettes, was a better model for the city of the future.

Even after the 1964 Olympics were over, I was unable to get Tanges gymnasium out of my mind, and at weekends I would travel by train from Yokohama to swim in the building. Watching the light falling from the top of the beautiful arched ceiling made me feel as if I was in heaven. As I swam silently, I would think to myself how I, too, wanted to create buildings that would, someday, move people in this way.

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics marked the peak of Japans economic development ... This exultant national mood was translated splendidly into architectural form by Kenz Tange.

In his book Empire of Signs (1970), the French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote that the centre of Tokyo is occupied by a void. Unlike European cities, where the central area is marked by an architectural focal point, such as a castle or a church, it is a quiet forest that lies at Tokyos heart home to the Imperial Palace, residence of the Emperor, surrounded by over 1 km2 (0.4 sq miles) of parkland and gardens.

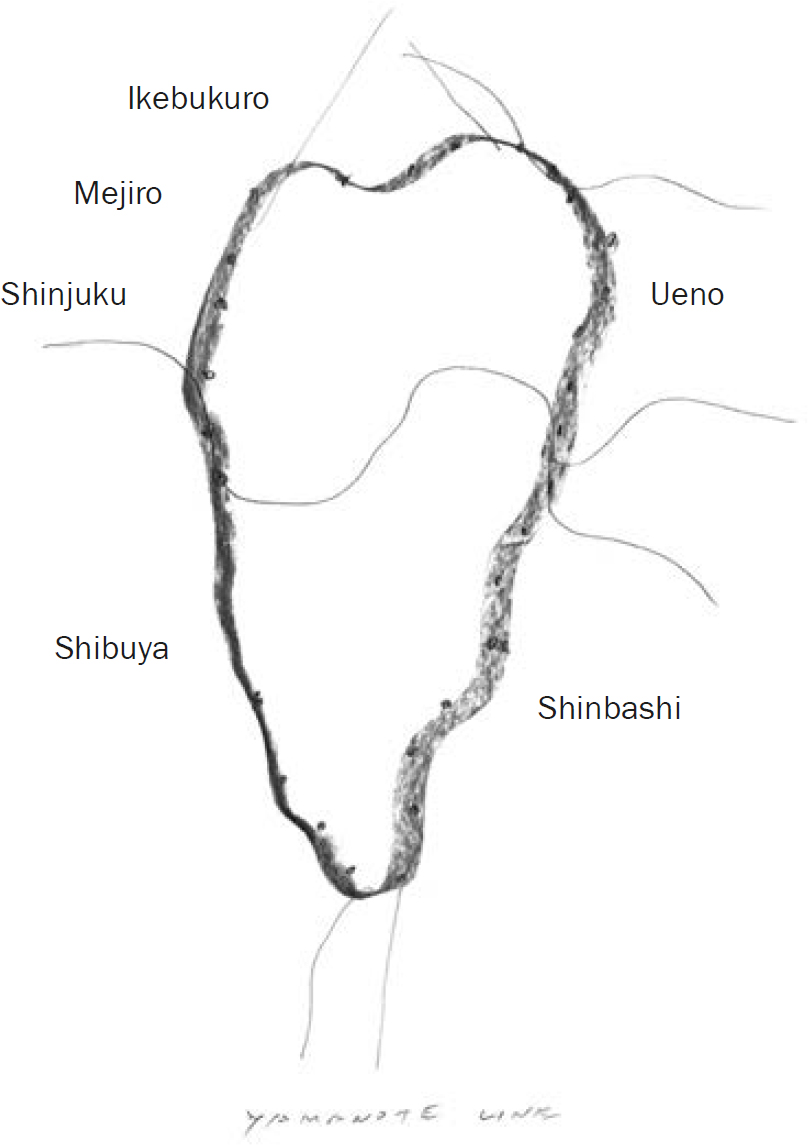

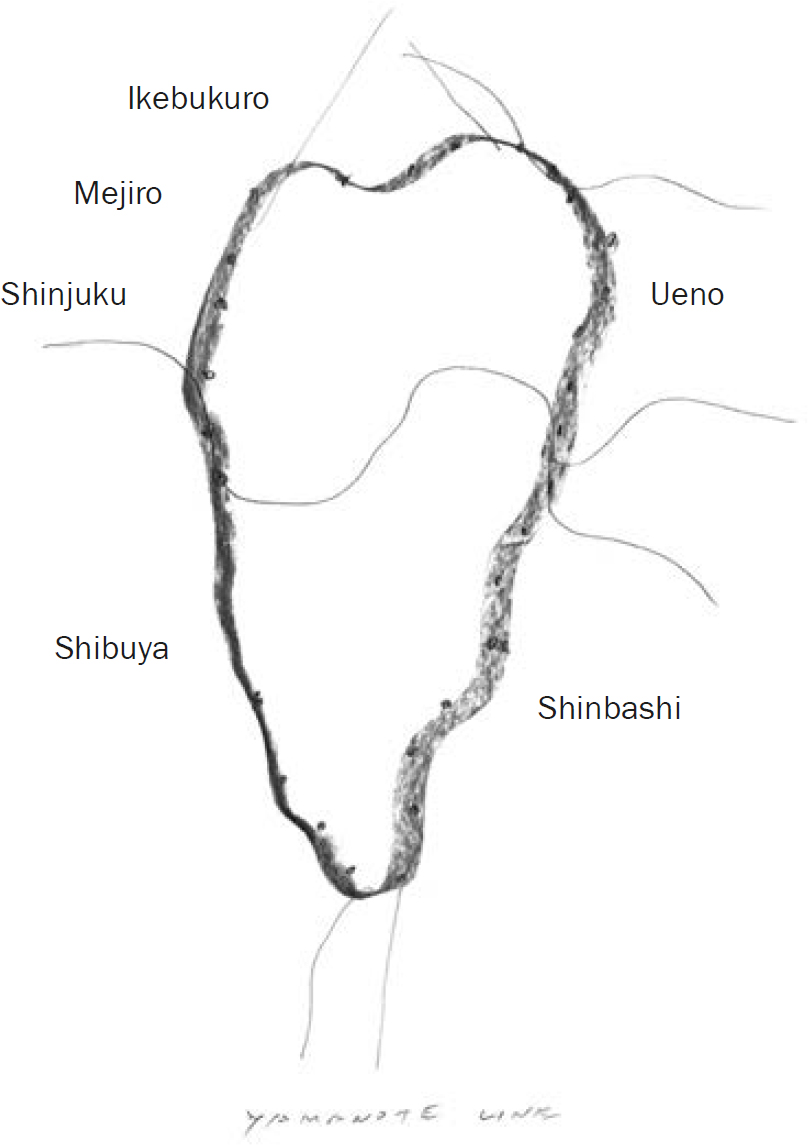

Barthes saw this as underlining how the structure of society and the urban landscape differ greatly between Japan and the West. The centre of Tokyo is certainly a void, but one that is protected by a circular train line, the Yamanote (see ), which forms a 40-km (25-mile) loop around it. It seems to me that this ring of steel emphasizes the importance of the void, and the depth of its significance.

An empty void in a citys central space is far more welcoming than any towering building. The Yamanote line passes through a number of terminal stations Shibuya, Shinjuku (the private railway lines that run out to the suburbs. It is used by over two million passengers each day. Around the empty centre formed by the palace grounds, these stations serve as the hubs of Tokyos financial and cultural activity.

Shibuya, in particular, is the centre of youth culture, and where I would go, from my childhood onwards, to hang out. On Halloween, great numbers of youngsters in costumes gather round the station, drinking and singing until morning. Halloween in Shibuya, in fact, could be called Japans biggest festival.