For Adam and Theo

Contents

Preface

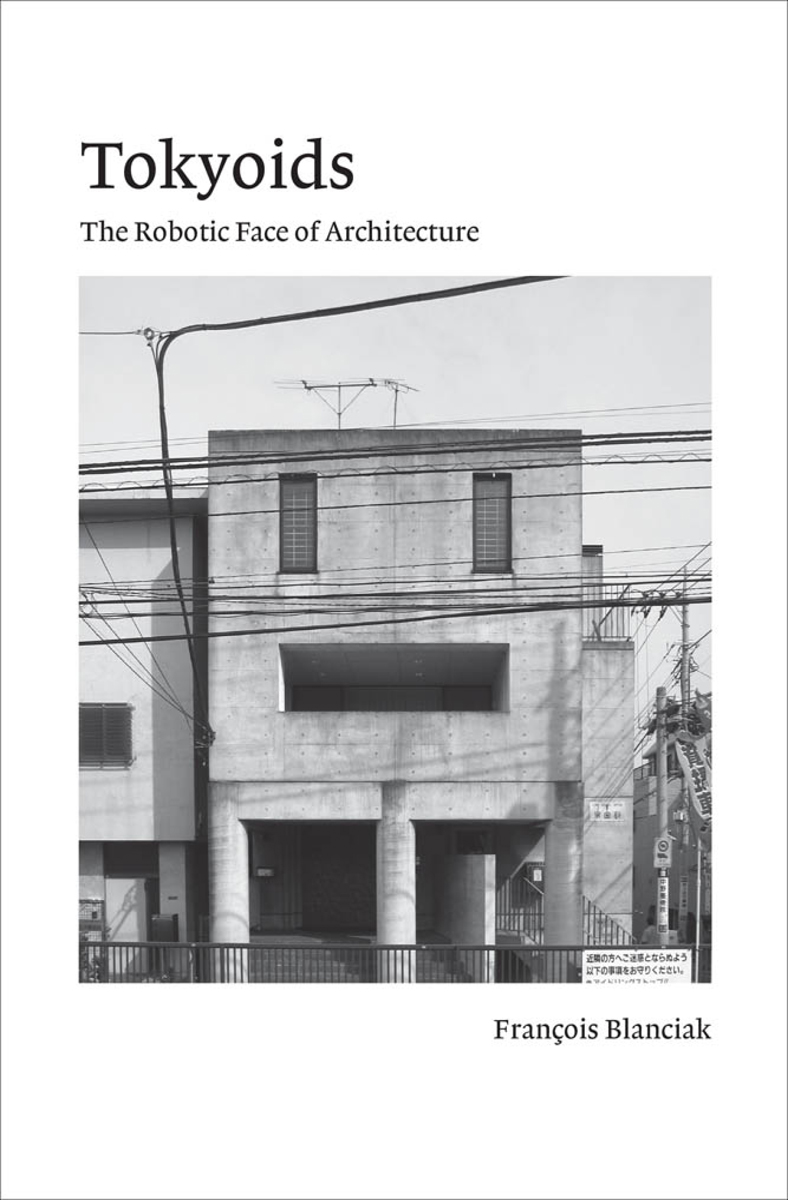

Many things can be accomplished by working long hours in an office, a studio, or a laboratory. The images that follow cannot. As a series of photographs that tracks a sporadic phenomenon within a vast and ever-changing urban environment, this content could only be gleaned extremely slowly. Shot between 2009 and 2019, the elusive and nearly dissimulated nature of the matter it revealssomehow showing up only when unexpectedmade the production of this survey a delicate exercise, further complicated by the rigidity of the photographic medium. These pictures are not those of a photographer who has received formal training in that field, but those of an architect who suddenly felt compelled to record what he saw.

This series, like seemingly all other photographic taxonomies, builds on the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, as well as of Edward Ruscha, but also, more saliently, on the research of Paul Virilio and Terunobu Fujimori, authors who have likewise strived to discern, through their own snapshots, architectural value in otherwise neglected structures. If the photographs shown in the following pages aim to depict a physical condition as is (involving only minimal variations in color and contrast), it is very much the architectural purpose of these picturestheir capacity to inflect design paradigmsthat I was interested in.

The reader will probably have already realized that this book is in fact two books in one. I have aimed to cultivate this idea so as to address (and hopefully to a certain extent reconcile) two audiences: one with a considerable amount of knowledge in the field of architecture, and the other with none. Despite the scholarly nature of this undertaking, the theme of the robotic faceimplicit in these picturesserved as a point of departure for what is essentially a personal reflection on the aesthetics of automation. While the effects of automation have recently been discussed at length, its very appearance has been less so. This is addressed here by investigating the relevance of the concept of the robotic face in architectural theory, and exploring links between the characteristics of the surveyed phenomenon and the specificities of its Japanese context. By focusing on the figurative, the text also attempts to transcend the penchant for abstraction of modern architectural and urban theories, which too often reduce cities and buildings to pristine patterns that misrepresent the complexity of urban experience.

Those familiar with my first book Siteless will probably see in this new output a bifurcation. It represents indeed an answer to a criticism (partly self-inflicted) that my work was fantastical in nature, and that I should therefore face reality. Yet similarities with this first opus abound. The focus is placed again on the very limits of digital tools in architecture (on what cannot be done with computers), following the earlier book's hypothesis that design software might be in the process of narrowing down the range of architectural possibilities. Because of its emphasis on the nonverbal, this second book also reflects a similar disbelief in the capacity of conventional writing to fully convey (and transmit in the longer term) architectural value. Building on this skepticism, Tokyoids draws a parallel between the structure of the Japanese language and architectural form through its search for the fundamentals of robotic aesthetics.

This research has benefited from encouragements and feedback from various individuals. Conversations with Shgo Kishida, Tom Heneghan, Gevork Hartoonian, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Martino Stierli, Jimenez Lai, Andrew Kovacs, Urtzi Grau, Neeraj Bhatia, Erik LHeureux, Puay-peng Ho, Chris L. Smith, Laurence Kimmel, Thierry Lacoste, and Julian Worrall have helped define its scope and form. I feel privileged to have had the chance to work on this project with the MIT Press's new senior acquisitions editor for art and architecture, Thomas Weaver, who managed to be at once my strongest supporter and toughest critic. Considerable debt is also owed to Cameron Logan, Mark Jarzombek, David Butler, and Alessandro Rossi for reading my manuscript early on and formulating constructive comments. Outside academia, in ways that particularly mattered to me given the ambition of this publication to open up architectural research to a wider audience, Masashi Nagamori, Yann Drossart, Nicolas Floquet, Xavier Marchand, David Boulakia, Amadou Tounkara, and most importantly Wan-Ling Ko have made useful suggestions. At the outset of this study, extensive, meandering, and often nocturnal walks in Tokyo with Keisho Sakamoto, Kaze Shind, Naoto Muta, Michael Koslowski, Jean-Franois Hirt, Eric Perrier, and Michael Gibert have played a decisive role in the development of a capacity to perceive the figurative in ostensibly abstract streetscapes. Properly documenting these encounters would not have been possible without the camera my brother Pierre, noticing my interest in this matter, gifted me.

Several institutions have been helpful in bringing this work to completion. I am grateful to the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, my home institution, for its generous support. The Bibliothque nationale de France, the Fondation Le Corbusier, the National Diet Library, and the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation provided access to useful materials, and considerately dealt with my requests. My gratitude also goes to the Government of Japan for its financial help during my seven-year stay in Tokyo.

Much of the prose that follows was produced from the confines of a children's bedroomthat of my sons Adam and Theo, to whom this book is dedicated. Being surrounded by the anthropomorphic effigies of Lightning McQueen and Thomas the Tank Engine likely had some impact on my writing.

Lastly, I feel the somewhat awkward need to thank the very buildings showcased heresince their personality is at stakefor simply revealing themselves to me. In an interview with Georges Charbonnier published in 1959, the French painter Andr Marchand recalled: In a forest, I have felt many times over that it was not I who looked at the forest. Some days I felt that the trees were looking at me. In many ways, the buildings of Tokyoids reflect this ontological projection. I saw them, they saw me. By exposing this intimate yet public relationship with the city, this book goes beyond its obvious autobiographical dimension, and allegorically seeks confirmation, in the eyes of others, of the very existence of architecture.

Introduction

Robots have invaded architecture schools. Indeed, the most striking change in the visual environment of these institutions over the last decade appears to have been the insertion of sophisticated automata into their midst. Entire departments have been reconfigured to accommodate them. Doors have been enlarged, rooms added, basements appropriated. Prominently showcased, though seldom active, these devices represent the new symbolic image of architectural educationthe contemporary equivalent of the Ionic capital. And yet these mechanical arms inherited from the automotive industry still challenge our conventional conception of robotic form. They are quite different from the man-made creatures of 1920s futuristic drama: at odds with the riveted curvaceousness of Fritz Lang's gynoid, or with the standardized realism of Karel apek's artificial humans. The boxy physique of the toy robots that sprang up in post-war Japan, with their stoic posture, bulging eyes, and gridded mouth, also contrasts with the morphology of these newcomers. Their legs severed, today's robots are unable to walk. Their faces excised, they are unable to see. Probing the implications of such ablations for building design, this book sustains the argument that this last missing partthe robotic faceis precisely what fundamentally relates robotics to architecture.