Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

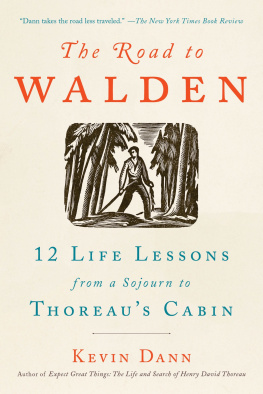

This is a lovely book, full of light, grace and meaning. Usher celebrates his passion for walking by exploring religious texts and stories, but this by no means confines his thoughts. We are drawn by secular texts too: Macfarlane sits alongside Kierkegaard; Thoreau and Walden alongside T. S. Eliot. Through them all, we learn why walking is so unspeakably good for heart, soul and body.

Dame Fiona Reynolds, Master of Emmanuel College Cambridge

Wonderful. Offers highly original and striking observations combined with apposite, moving and often humorous personal anecdotes. A classic, catching a genuine and humble holiness.

Bishop David Wilbourne

Graham Usher is the Bishop of Norwich and an ecologist.

First published in Great Britain in 2020

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

36 Causton Street

London SW1P 4ST

www.spck.org.uk

Copyright Graham B. Usher

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

SPCK does not necessarily endorse the individual

views contained in its publications.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780281084067

eBook ISBN 9780281084050

Typeset by Nord Compo

First printed in Great Britain by Jellyfish Print Solutions

Subsequently digitally printed in Great Britain

eBook by Nord Compo

Produced on paper from sustainable forests

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

Rachel,

with thanksgiving for our walking together.

Traveller, your footprints

are the only road, nothing else.

Traveller, there is no road;

you make your own path as you walk.

As you walk, you make your own road,

and when you look back

you see the path

you will never travel again.

Traveller, there is no road;

only a ships wake on the sea.

(Antonio Machado, 18751939)

Acknowledgements

I am particularly grateful to John Inge for enabling me to have a period of sabbatical study leave to write this book and to my former colleagues in the Diocese of Worcester for stepping in to cover many of my responsibilities, especially Stuart Currie, Nikki Groarke, Robert Jones and Robert Paterson.

The Gerald Palmer Charitable Trust, the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association, and the Church Commissioners for England were generous in providing sabbatical grants, together with the Ecclesiastical Insurance Group who gave a Ministry Bursary Award. These enabled me to spend time walking, thinking and praying on the Holy Mountain of Mount Athos, in the Troodos Mountains and Akamas Peninsula of Cyprus, and in the Judean Wilderness of the Palestinian Territories. I am grateful to the principal, staff and ordinands of The Queens Theological Foundation for Ecumenical Theological Education in Birmingham who provided me with a room to work in, with library and online resources, as well as good conversations and encouragement during my research and writing.

I have been enriched by the work of many authors. Robert Macfarlane, whose tweets and books I enjoy, helped with referencing some of Nan Shepherds work; Michelle Painter of West Midlands Police pointed to information about the use of gait in forensic identification; and orthopaedic surgeon Charlie Docker taught me the mechanics of walking. The staff of the British Library, especially Melanie Johnson, were unfailingly helpful.

I am grateful to Yasser, Amer, Shiraz, Mary, Akbar, Ismaeel, Sumbul, Abdullah, and Baqaburinedi (some decided to use pseudonyms) for sharing their moving experiences of walking as refugees. I will long remember the experience of sitting and listening to them. Andrew Harwood, Anne West, Joy and Jeremy Parkes, and Jeremy Thompson were crucial in setting up these meetings and creating spaces for trusted listening.

Helen Shakespeare proofread early chapters of the book, as well as undertaking some background research, recording refugee stories, and making travel arrangements. Catrine Ball and Leonie Andrewes helped with the transcripts of the stories of refugees. Katharine Bartlett proofread the whole manuscript and offered helpful suggestions.

I am indebted to Helen-Ann Hartley, Jonathan Kimber, Rick Simpson and David Wilbourne for commenting on the draft manuscript. Their guidance has enriched the final text, though any remaining errors are entirely my own.

Alison Barr at SPCK has been gracious with her editing and has undoubtedly enhanced the quality of the finished book.

None of this writing would have been possible without the support of Rachel, Olivia and Chad, and the walks we have enjoyed/suffered/complained about (delete as appropriate) over the years.

Every effort has been made to seek permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book. The publisher apologizes for those cases where permission might not have been sought and, if notified, will formally seek permission at the earliest opportunity. The publisher and author acknowledge with thanks permission to reproduce extracts from the following:

Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Anglicized Edition, copyright 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

W. H. Auden, For the Time Being, in Collected Poems, London, Faber and Faber, 1945.

Thomas A. Clark, In Praise of Walking and A Walk by Moonlight, are used with permission.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding, is reproduced with permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken, in Early Poems, London, Penguin Books, 1998.

Taiz Community, Let all who are thirsty come, is copyright Ateliers et Presses de Taiz, 71250 Taiz, France. Used with permission.

R. S. Thomas, The Absence, Somewhere and Pilgrimage, in Collected Poems 1945-1990, London, Phoenix Press, 2001.

Wild Goose Resource Group, Iona Community, Will you come and follow me text excerpt from The Summons, by John L. Bell, copyright 1987 WGRG, c/o Iona Community, Glasgow, Scotland.. Reproduced with permission.

Rowan Williams, Rublev, is used with permission.

Starting

A conversation when I was a fairly new vicar has long haunted me. In the early hours of the morning the doorbell of the vicarage was being repeatedly rung, not an infrequent occurrence in that place. Bleary-eyed and disorientated, I got out from under a warm duvet as I wondered whether the ringing bell was just part of the dream that had been stalking my sleeping mind. I stumbled through the darkness, stubbed a toe on the corner of the bed, cursed, opened an upstairs window and leaned out.

Father, will you give us a lift? asked one of the two women dressed for work.

We need to get to Grove Hill, said the other, yawning and leaning on the front door, looking up at me with big eyes. My fellas forgotten to come for us.

Do you know what time it is? I asked somewhat stupidly before stating the obvious. Youve woken me up.

Well will you give us a lift or not?

No!

Then came the killer guilt-inducing line for any priest.

Jesus would have done.

No, he wouldnt. Jesus didnt have a car. He walked everywhere and so can you.

Go f**k yourself! What kind of priest are you?

I closed the bedroom window, went back to bed and didnt sleep a wink. I couldnt turn off my conscience. Questions flooded my mind. Scenarios were played out in multi-coloured detail. What kind of priest are you? flashed like the lights which blinded St Paul on his Damascus road. What would Jesus have done? Would he have taken the risk? He kept company with prostitutes, didnt he? What if I had been pulled over in the car by the police and the two women had delighted in telling a different story? Should I have phoned for a taxi and paid their fare? Having in recent months buried two of their number, following a murder and an overdose, and offered pastoral care to the street community, didnt my actions now say, loudly and clearly, that I didnt really give a damn? What if one or both were harmed trying to get home? What would it mean to walk with them, to stagger in their high-heeled shoes, to feel the cold enveloping their shoulders, to know the deep ache that was only eased by crack cocaine, and the desperation etched on taut skin?